TANGO TRANSLATION TYPOGRAPHY

A Virtual Exhibition on Vasily Kamensky’s »Tango with Cows«, Avant-Garde Poetics, Popular Culture and Futurist Resonance

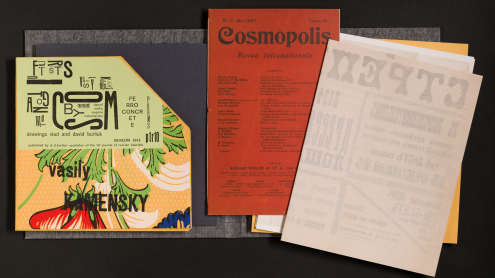

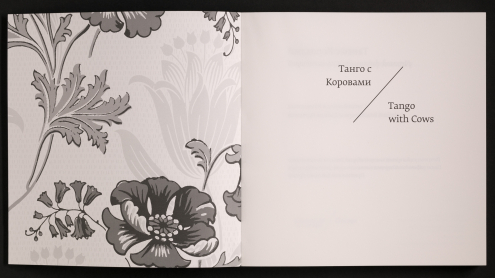

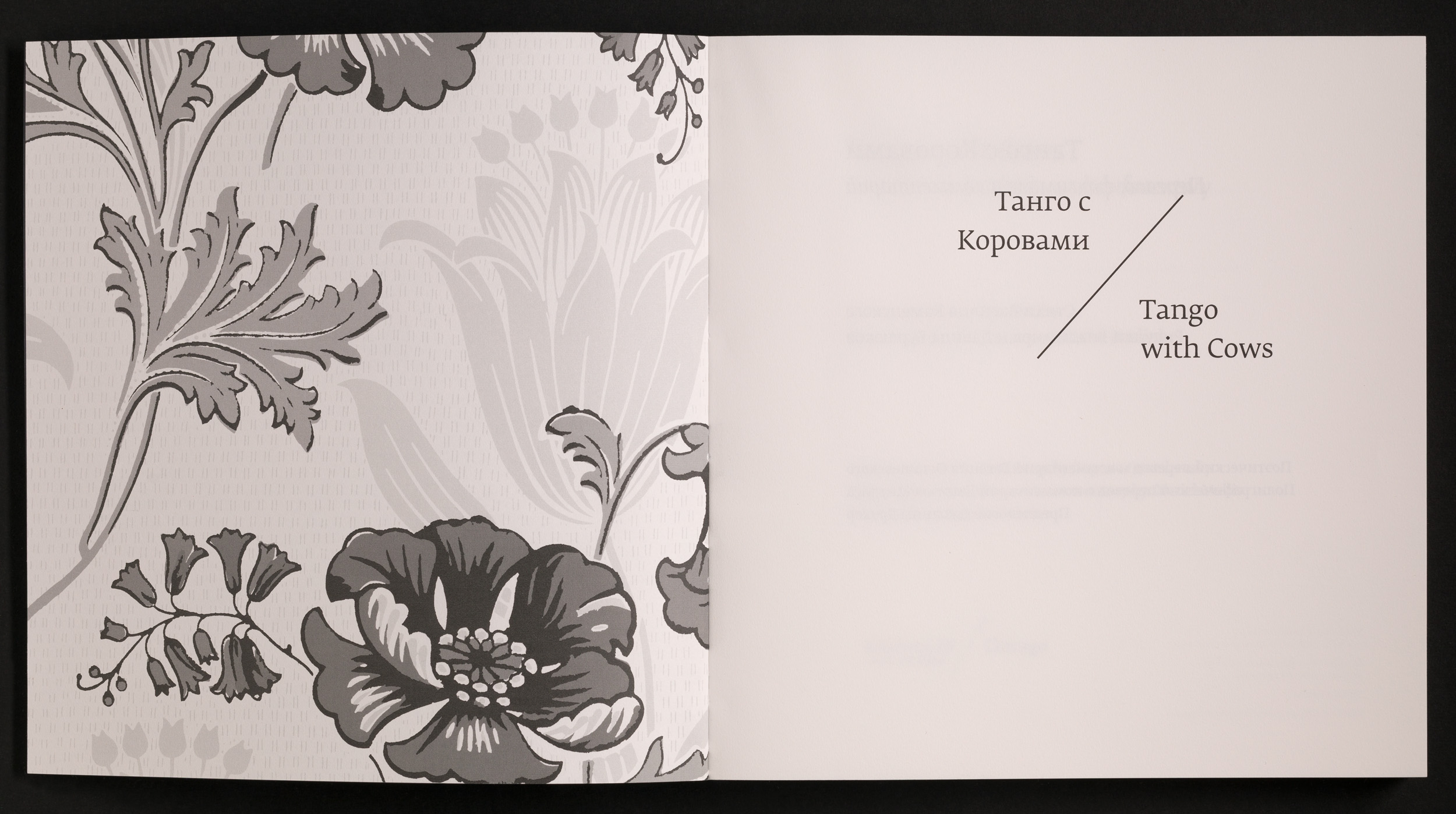

In 1914 Vasilij Kamenskij published Tango with Cows (Танго с коровами), a volume of poetry and a key work in the history of Russian Futurism, graphic design and artists’ books. Even the choice of pentagonal pages breaks with traditional notions of publishing, and the poems are equally impressive for their poetic innovation and their unusual design. The most experimental poems in the book, which is printed on floral wallpaper, are entitled “Ferroconcrete Poems” and explore the spatial possibilities of the printed page beyond linear order and design conventions, thus inventing a new type of visual poetry between the figurative and the concrete. Award-winning poet and translator Eugene Ostashevsky and designer Daniel Mellis have translated Kamensky’s work into English, focusing their attention on the special interplay between the Futuristic poems and their typographic design. On the occasion of the intricately designed and translated edition being donated to the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, the project TANGO TRANSLATION TYPOGRAPHY explores Kamensky the Futurist artist and his exceptional work, the historical interrelations between the avant-garde and popular culture, and Futurist publishing and collaboration practices around 1910 on multiple levels.

The virtual exhibition from the holdings of the Staatsbibliothek and the translator’s private collection is complemented by three online material-based conversations between Eugene Ostashevsky and researchers from the Cluster of Excellence »Temporal Communities: Doing Literature in a Global Perspective« at Freie Universität Berlin. Drawing on the rich archival treasures of the Staatsbibliothek, these conversations explore a wider historical and thematic sphere by probing questions of words in movement, translation and the translatability of poetic artworks, transnational Futurist resonances and the avant-garde fascination with flying.

A cooperation with the Cluster of Excellence »Temporal Communities: Doing Literature in a Global Perspective«

Vasilij Kamenskij / Vasily Kamensky

Kamenskij, Vasilij

Devuški bosikom. Stichi. Tiflis, 1916.

Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz

Signatur: 50 MA 7351

Kamenskij, Vasilij

Žiznʹ s Majakovskim. Moskva, 1940.

Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz

Signatur: Ax 6678/3/66

Kamenskij, Vasilij

Avtobiografija. Kak ja žil i živu. Tiflis, 1927.

Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Rara-Sammlung

Signatur: 421355

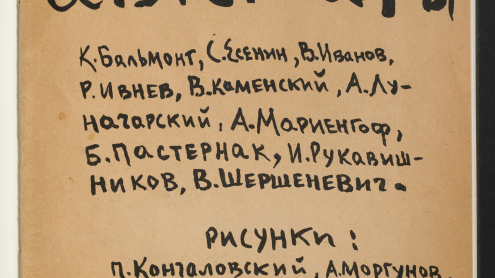

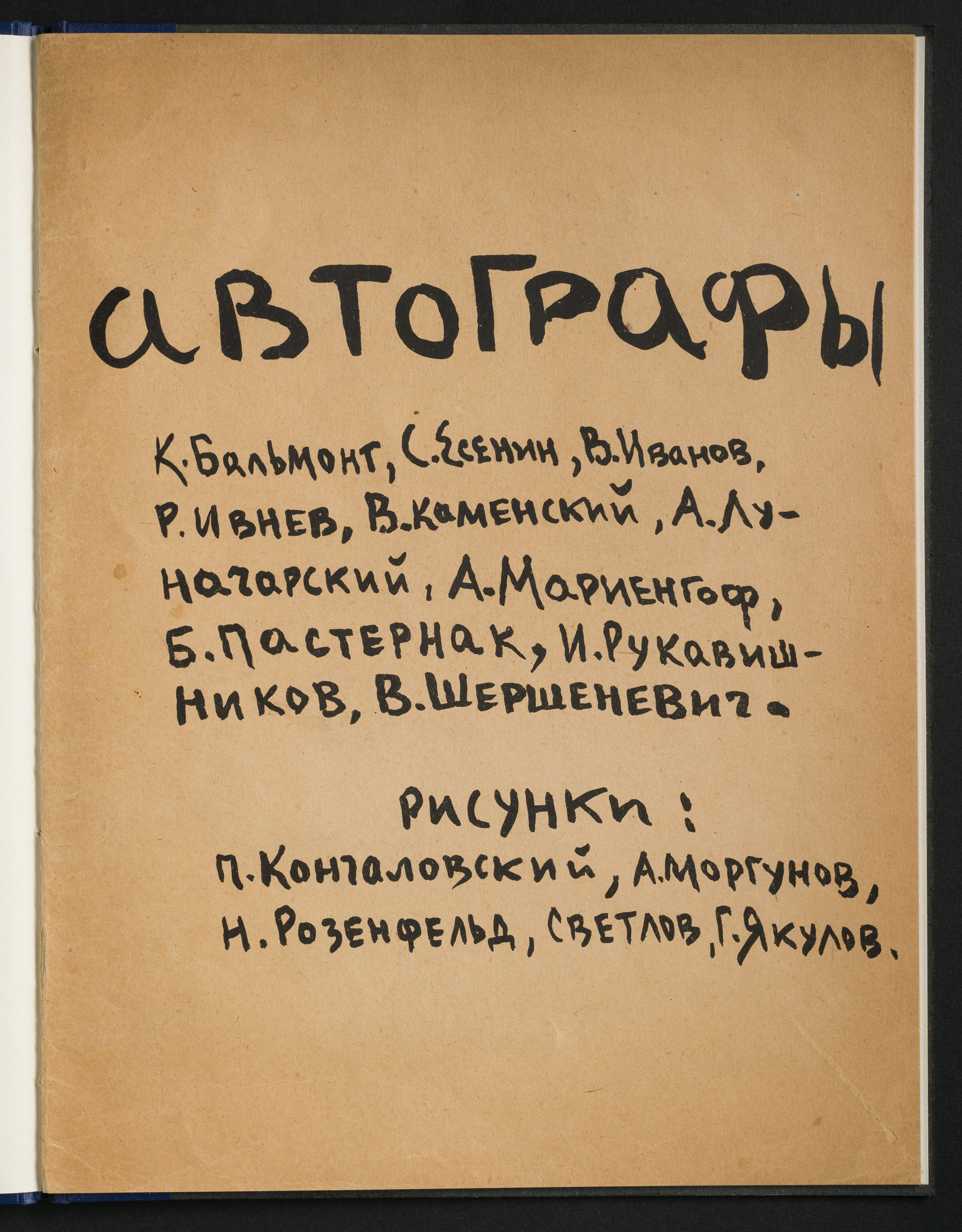

Avtografy. V. Kamenskij u.a. Faksimileausgabe. S.l., nach 1920.

Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz

Signatur: 4“ 824337

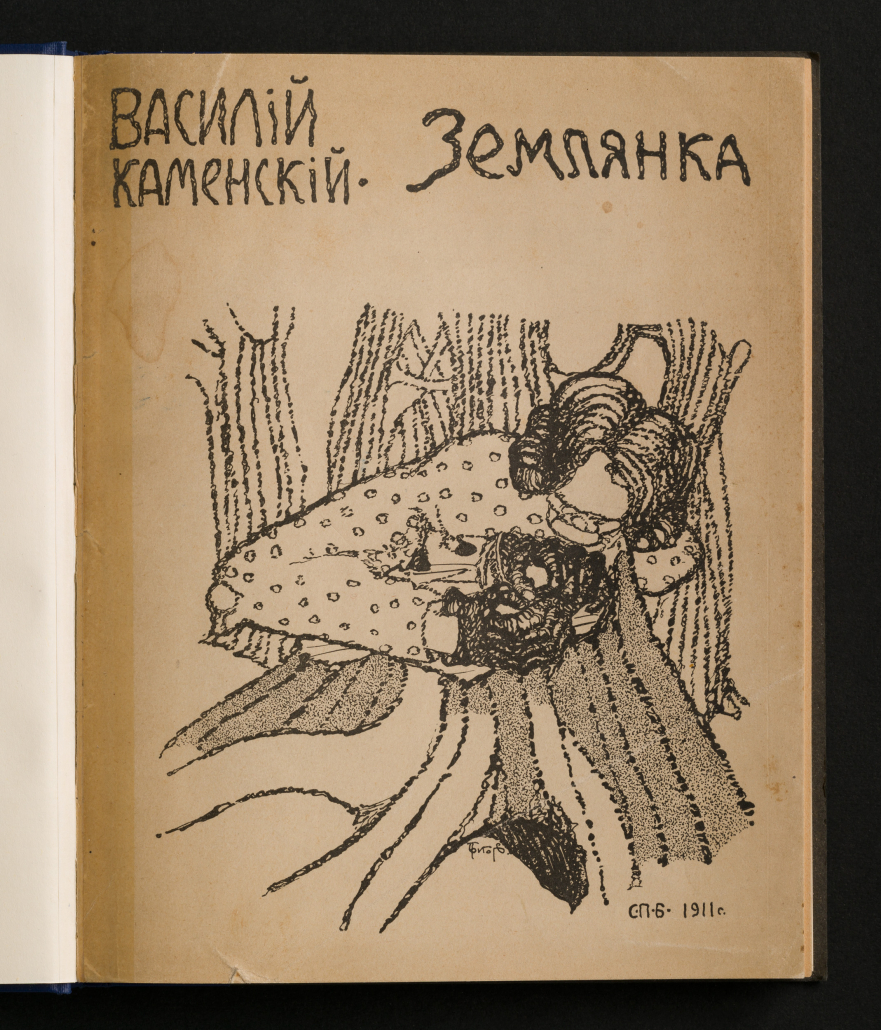

Kamenskij, Vasilij

Zemljanka. Sankt-Peterburg, 1911.

Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz

Signatur: 3 A 21407

Kamenskij, Vasilij

Zemljanka. Sankt Petersburg, 1911.

Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz

Signatur: 3 A 21407

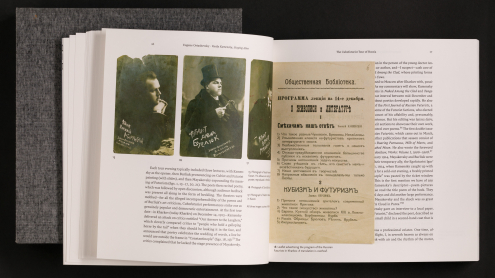

Kamensky was born in 1884 near the town of Perm, close to the Ural Mountains. After an adolescence spent working on the railroad, touring as an actor and being imprisoned for organizing strikes during the Revolution of 1905, he moved to St Petersburg. There he edited the literary journal The Spring (Vesna), took part in exhibitions as a painter, wrote poems and helped form the nascent avant-garde circle that included the poet Victor (Velimir) Khlebnikov, the painter David Burliuk and his siblings, the composer Mikhail Matiushin and the writer Elena Guro. In early 1910 Kamensky edited the group’s anthology Critics Creel (Sadok sudei), considered in hindsight to be the first Russian Futurist publication. It was printed on wallpaper, as Tango with Cows would be four years later. He finished his next project, the experimental novel The Earth Hut (Zemlianka, see image), while on vacation that summer. The narrator of this impressionist prose-and-poetry work abandons the inhuman city of modernity for life in an earthen hut in the forest. The book was illustrated by the young modernist Boris Grigoriev (1886-1939). Unfortunately, the release of The Earth Hut in November 1910 coincided with the death of Leo Tolstoy. “The whole world being occupied with the great passing of Tolstoy, it had no time for my novel,” wrote the disappointed author. Shortly after the botched release he quit literature for aviation.

Kamenskij, Vasilij

Devuški bosikom. Stichi. Tiflis, 1916.

Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz

Signatur: 50 MA 7351

To escape conscription during World War I, Kamensky toured near the Black Sea with Vladimir Holzschmidt, the self-styled “Futurist of Life,” who lectured on yoga, hypnotized chickens and broke wooden boards with his head. In the fall of 1916, Kamensky stayed in cosmopolitan Tiflis (today known as Tbilisi). There he met young Russian avant-garde poets, the Blue Horns group of Georgian modernist poets, the Armenian Futurist Kara-Dervish and the professional wrestler Ivan Zaikin, who got him a gig with the Yesikovsky Brothers Circus. For seven nights between October 19 and 25, 1916, Kamensky declaimed poems while riding a horse around the ring. He recounts this experience in one of the last poems of Girls Barefoot (Devushki bosikom), a collection published in Tiflis in November: “I was the First Poet in the World / Who magnificently appeared / On the Circus arena / In a kaftan of brocade / And astride a black horse—/ I put up a monument to myself / Under the big top and trapeze.” He was so successful as a circus poet that a poster of the Sukhumi circus from November 1920 lists “the pride, beauty, and coryphaeus of Russian Futurism Vasily Kamensky” as the show’s main attraction.

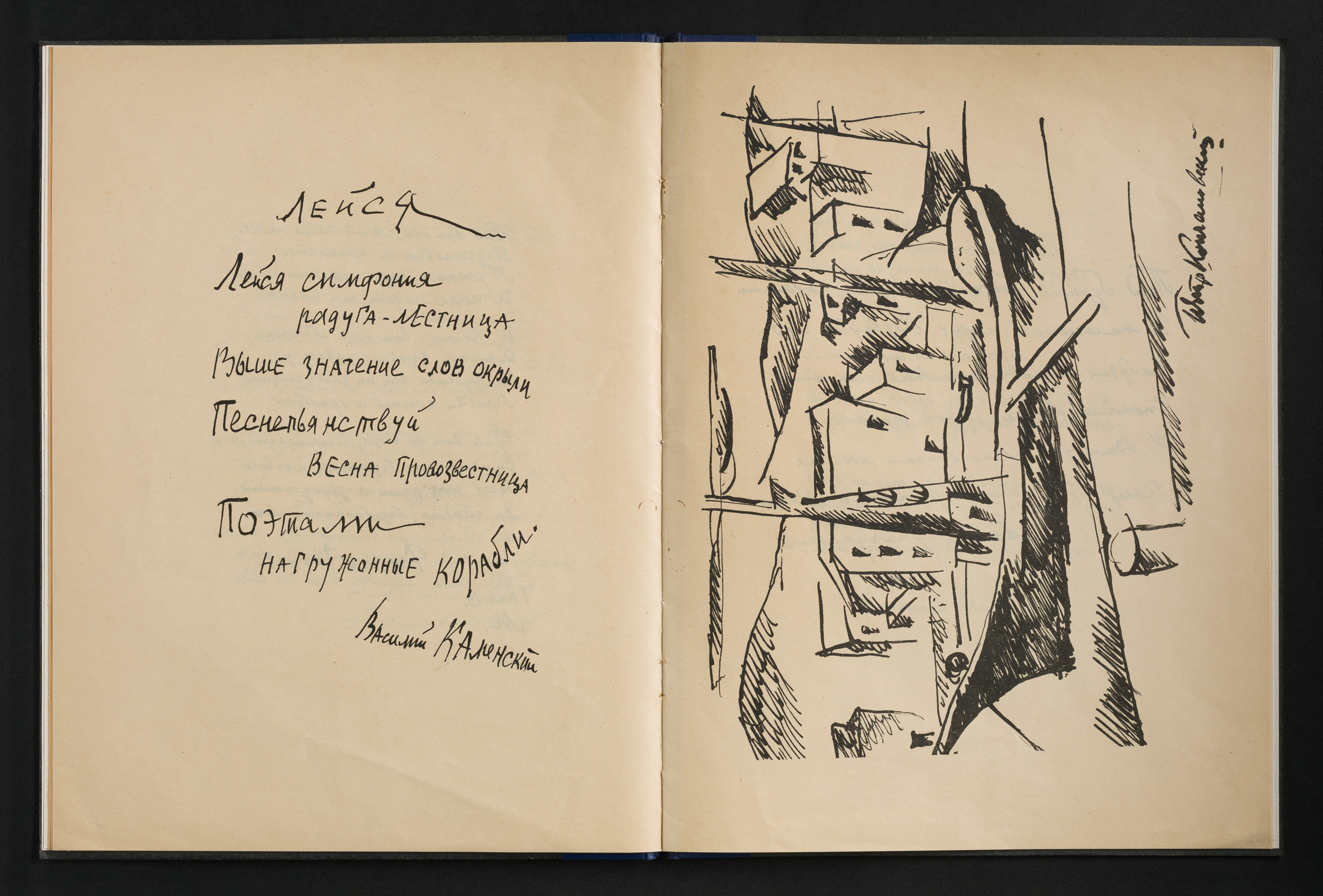

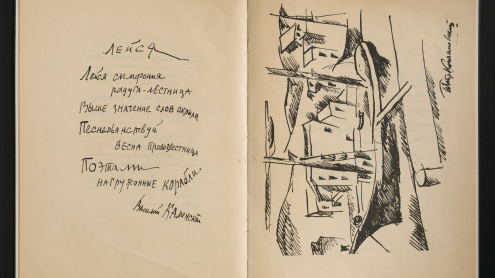

Avtografy. V. Kamenskij u.a. Faksimileausgabe. S.l., nach 1920.

Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz

Signatur: 4“ 824337

This collection of author autographs put together in the early 1920s shows four lines from Kamensky’s long poem Tsuvamma, a meaningless name of his invention, in his own handwriting. Located either above the Polar Circle or in the stars above it, the utopia of Tsuvamma is inhabited by either poet-aviators or poet-birds. The strongly rhythmical poem, first published in its entirety in Tiflis (Tbilisi) in 1920, is full of made-up words, some of which are easily legible compounds and some of which are abstract sound structures.

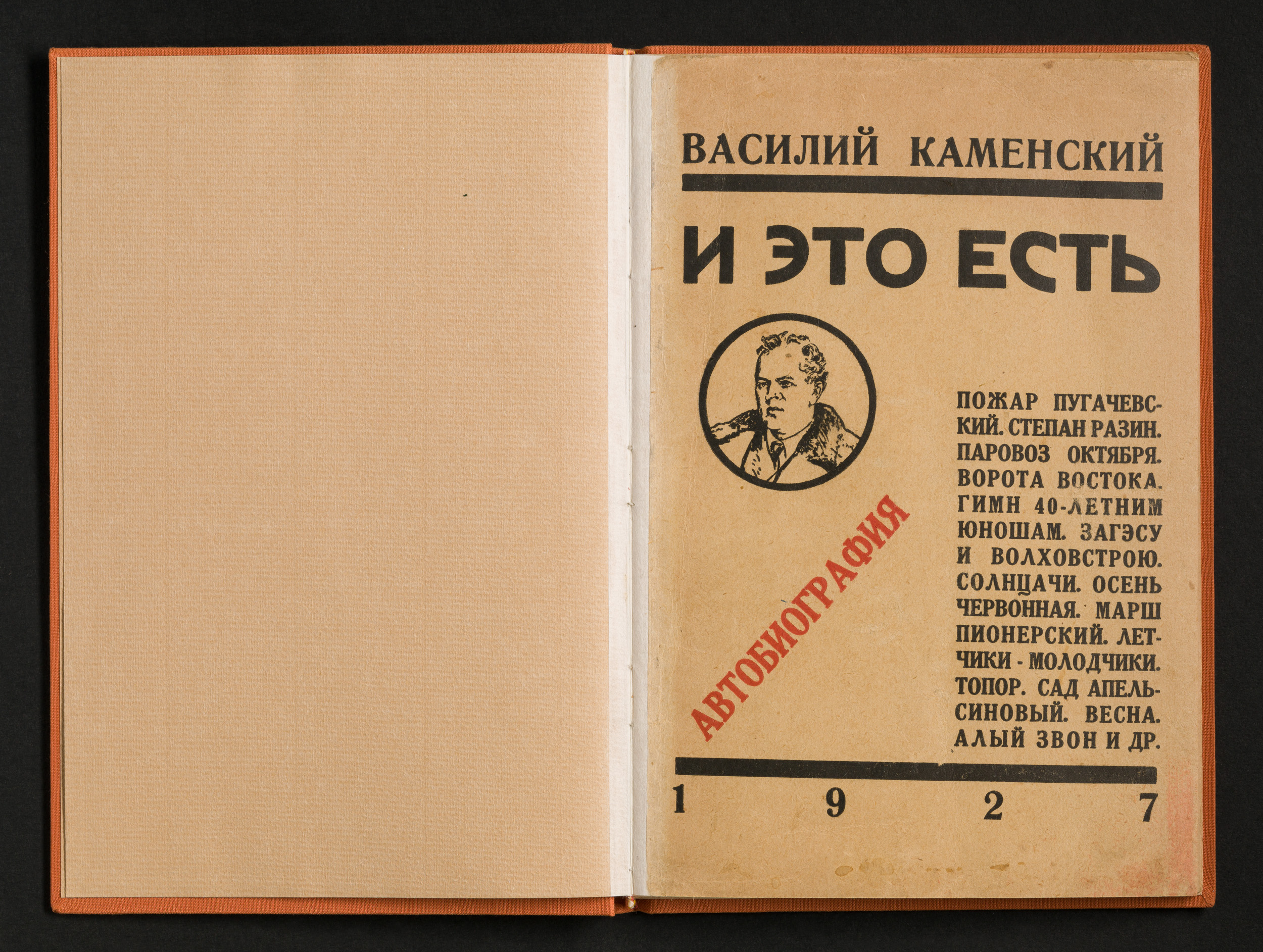

Kamenskij, Vasilij

Avtobiografija. Kak ja žil i živu. Tiflis, 1927.

Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Rara-Sammlung

Signatur: 421355

In the late 1920s and early 1930s Kamensky published several titles with the Russian-language publishing house Zakkniga (Transcaucasian Book), run by his long-time friends in Tiflis (Tbilisi). And There’s This, Too: Autobiography and Poems (I eto est’: Avtobiografiia, poemy, stikhi) opens with an autobiography of several pages. It represents the author as an enthusiastic, hard-working, politically-minded proponent of the new world and a lover of nature to boot. The poems that follow are mostly in praise of industrialization. As much of Kamensky’s work, they are rich in rhythmic and phonetic effects, created to be read out loud with great energy. Vladimir Mayakovsky and Victor Shklovsky also published with Zakkniga at the time.

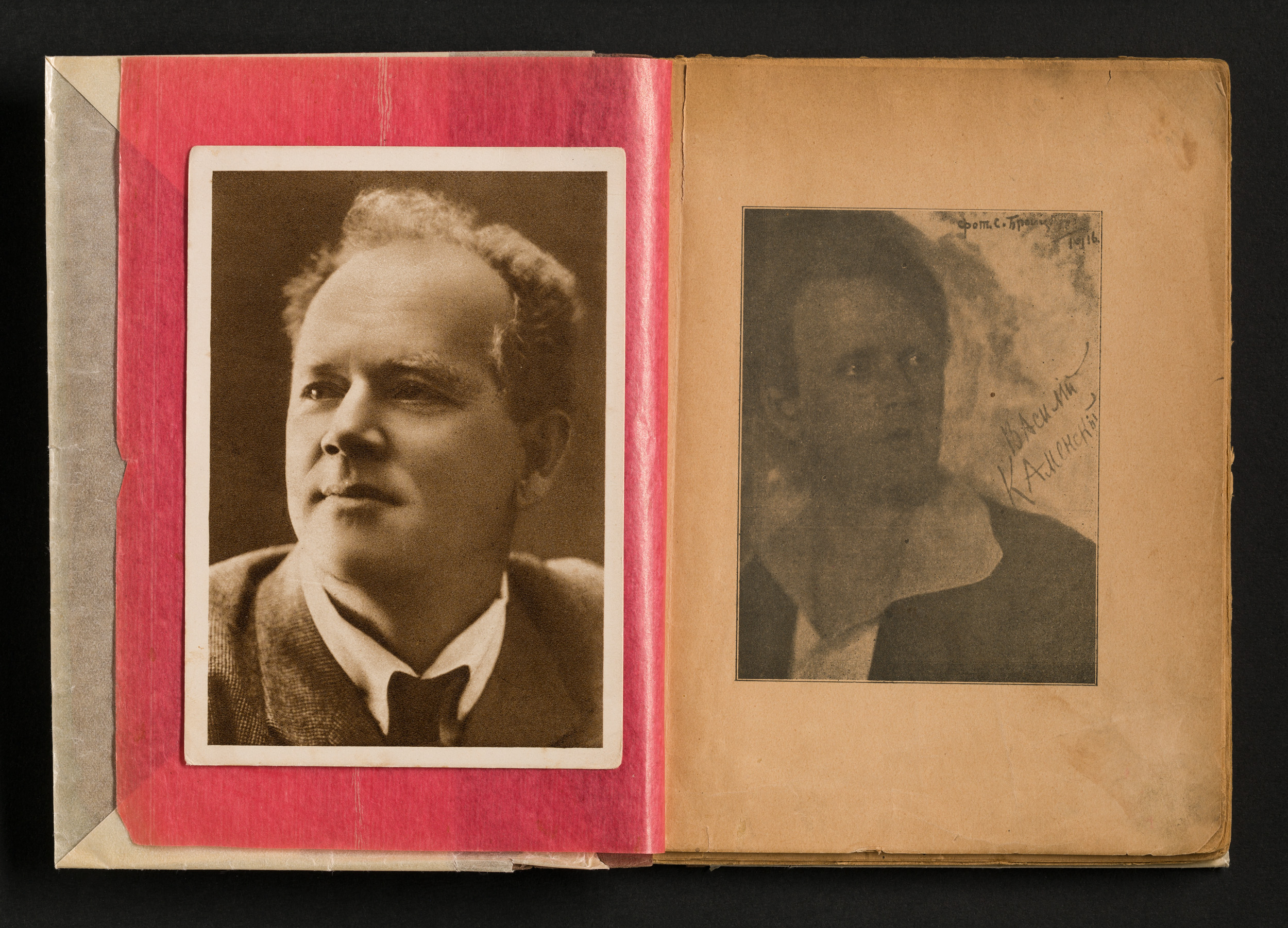

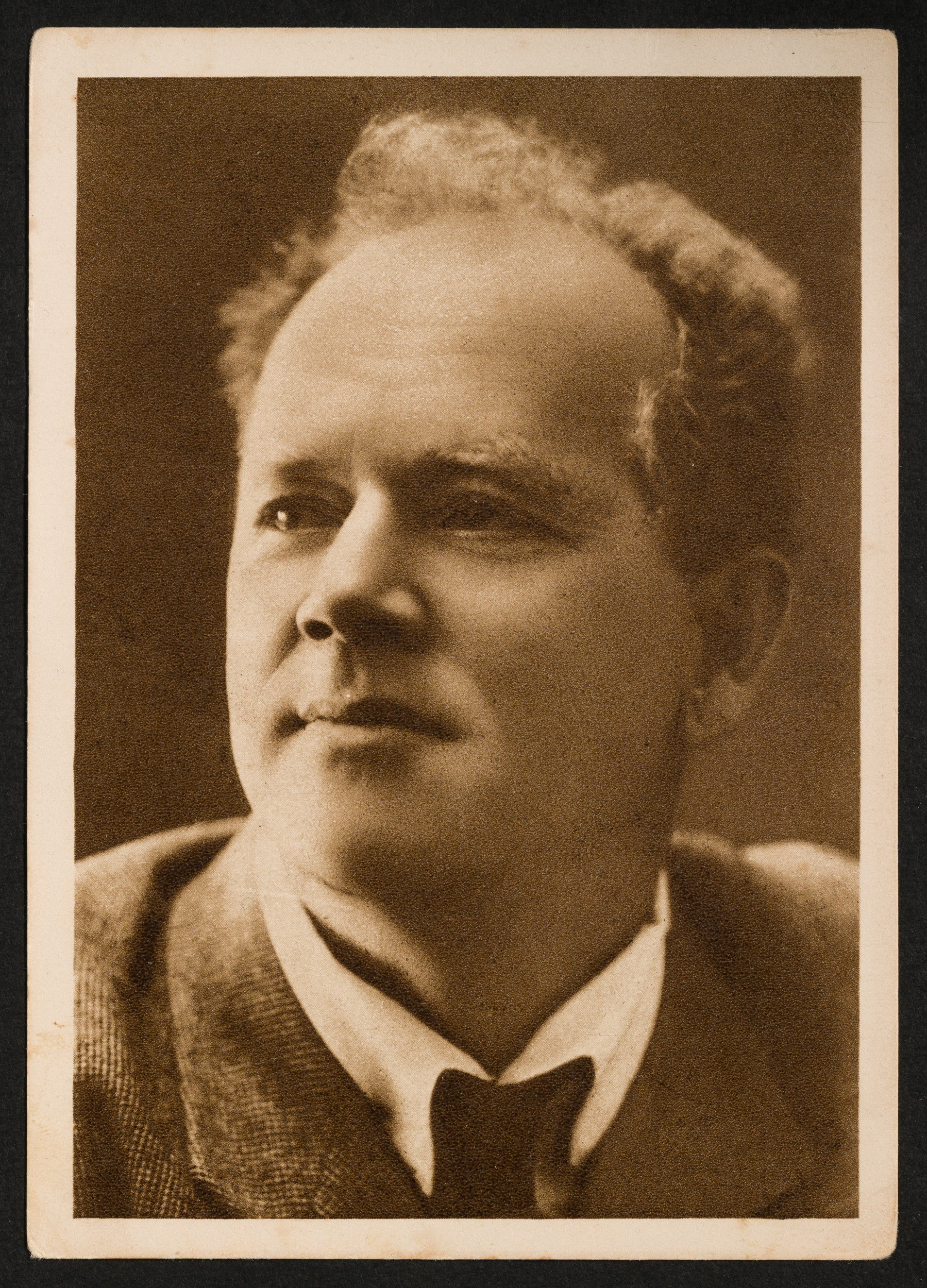

V. V. Kamenskij. 1934.

Privatsammlung

In 1932-33, the Soviet state celebrated prominent writers to show the benefits of state patronage on the eve of forming a single Union of Soviet Writers. The main celebration of Kamensky’s 25th anniversary of literary activity took place in the Grand Hall of the Moscow Conservatory on March 26, 1933. The poet wrote to a friend that he was placed on a throne, crowned with laurels and serenaded by “the best wind orchestra of the USSR—that of the OGPU,” the political police. Two thousand spectators were in attendance. Lazar Kaganovich, the Politburo member who took care of literature when not too busy orchestrating the mass terror-famines of 1932-1933, kindly sent Kamensky a truckload of firewood as a surprise gift. Later that year, the poet was also celebrated in Soviet Georgia and Azerbaijan. This postcard shows Kamensky on his fiftieth birthday in 1934. That was the year a competitor prevented him from becoming a representative at the First Congress of the Union of Soviet Writers, which possibly saved his life during the Great Purge of 1937-1938, when a third of the participating writers were shot.

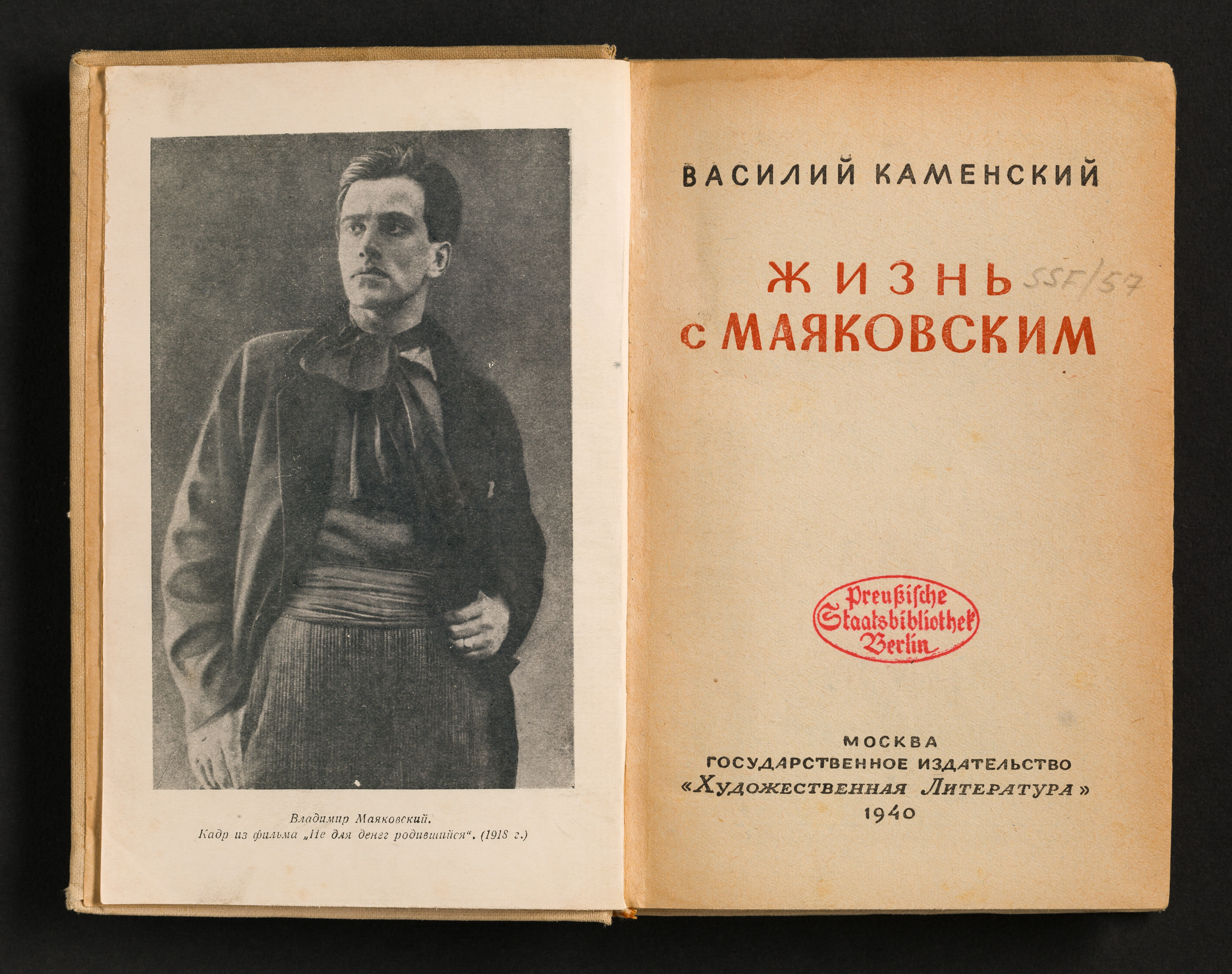

Kamenskij, Vasilij

Žiznʹ s Majakovskim. Moskva, 1940.

Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz

Signatur: Ax 6678/3/66

At the end of the 1920s, former Futurists took up memoir writing. Kamensky revisited his Futurist years in three major works: Mayakovsky’s Youth (Iunost’ Maiakovskogo, 1931), The Way of the Enthusiast (Put’ entuziasta, 1931) and My Life with Mayakovsky (Zhizn’ s Maiakovskim, 1940). Mayakovsky killed himself in 1930 but his Soviet career served to justify the preservation of the memory of Russian Futurism in subsequent decades. The frontispiece of the memoir shows the poet in 1918, when he starred in a silent film based on Jack London’s novel Martin Eden. Kamensky’s reminiscences are lively but their historical accuracy sometimes falls victim to literary effect.

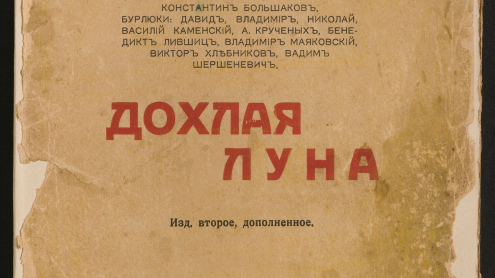

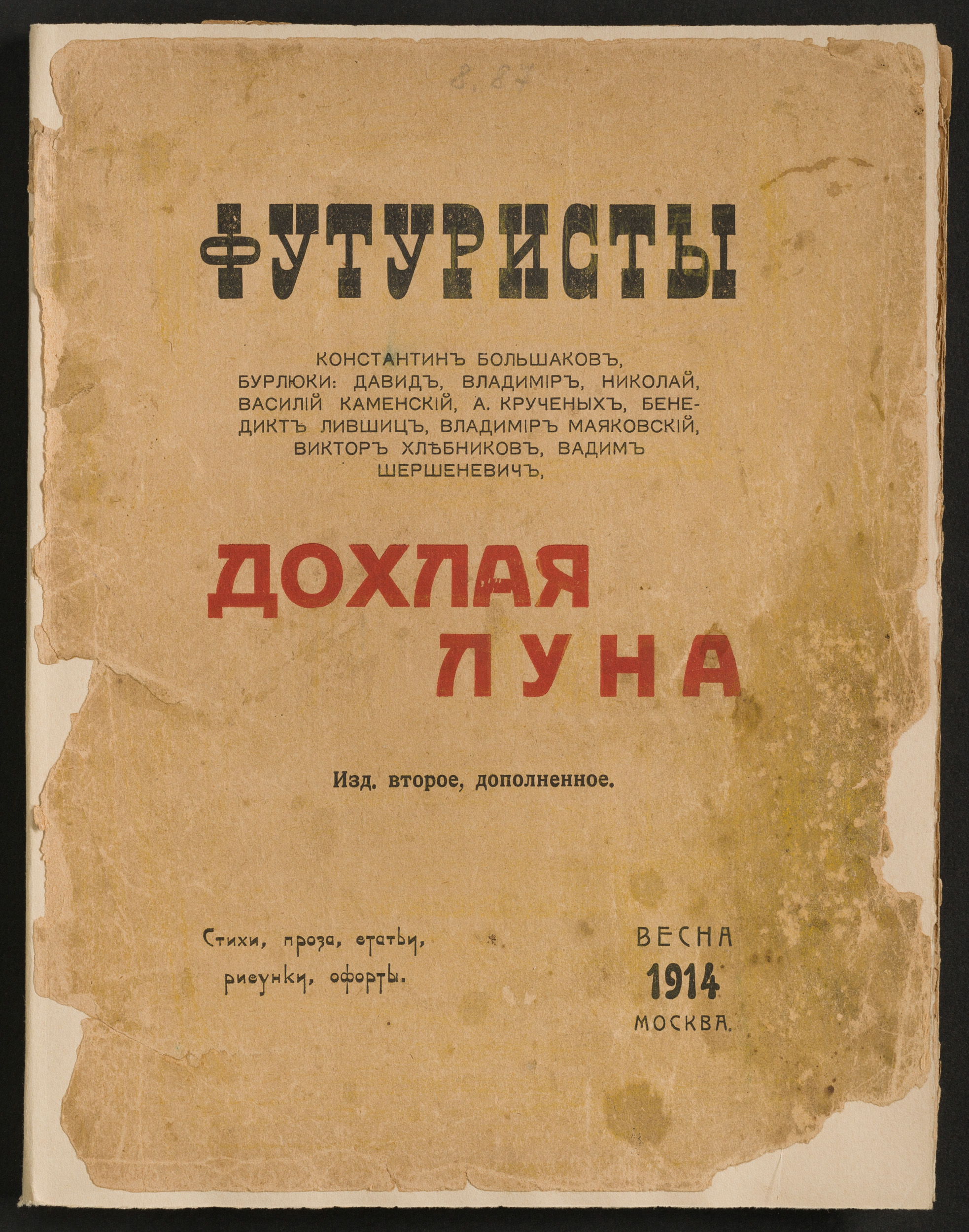

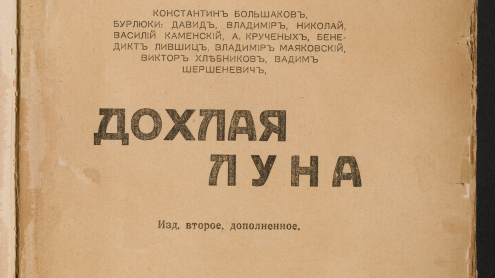

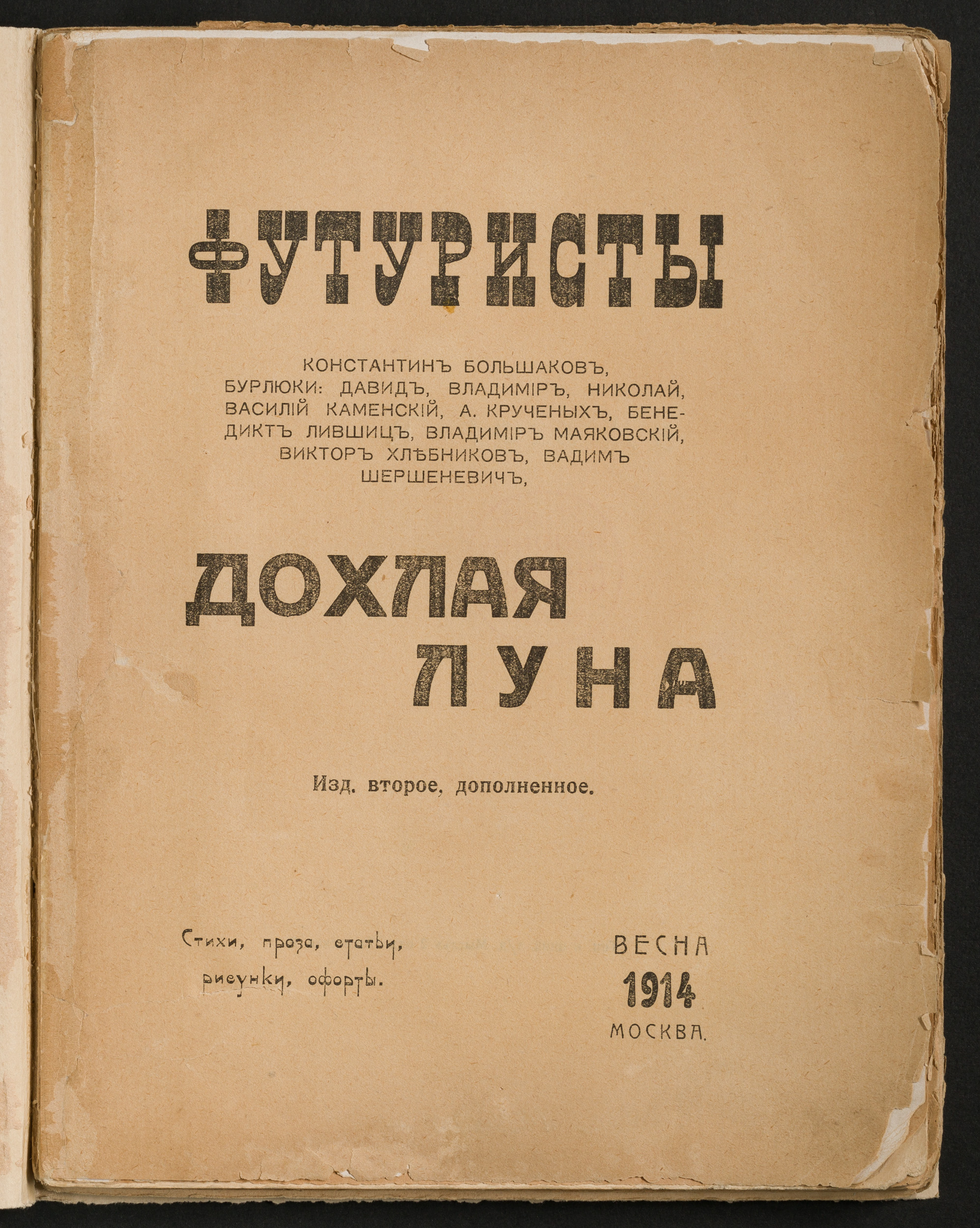

Futurist Networks

Dochlaja luna. Futuristy Konstantin Bol’šakov, Burljuki: David, Vladimir, Nikolaj, Vasilij Kamenskij, A. Kručenych, Benedikt Livšic, Vladimir Majakovsij, Viktor Chlěbnikov, Vadim Šeršenevič. Stichi, proza, stat’i, risunki, oforty. Izd. 2., dop. Moskva, 1914.

Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Rara-Sammlung

Signatur: 3 A 6201

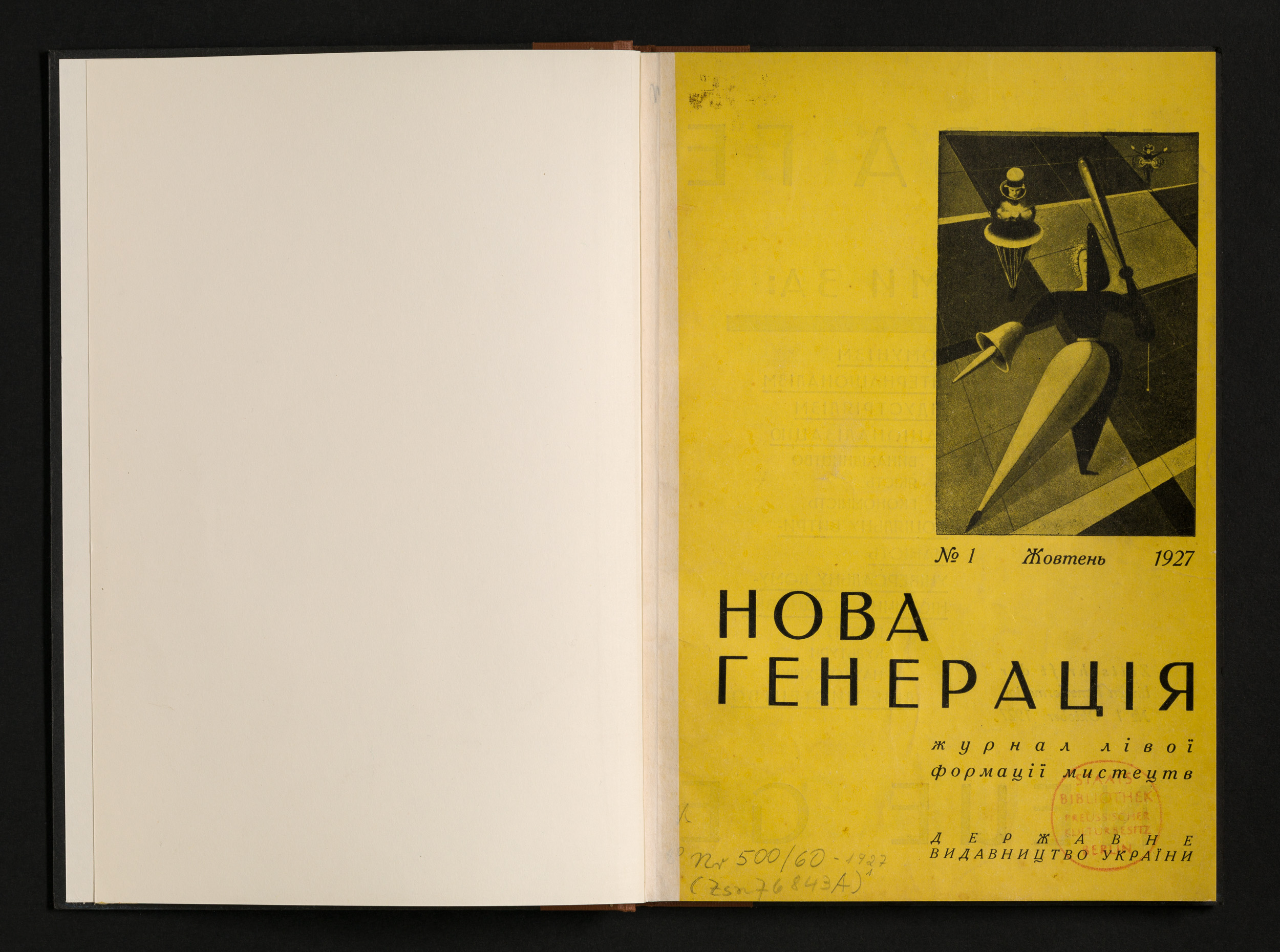

Nova generacija. Žurnal livoï formaciï mystectv. Charkiv, 1927.

Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz

Signatur: Nr 500/60-1927,1/3(N=2)

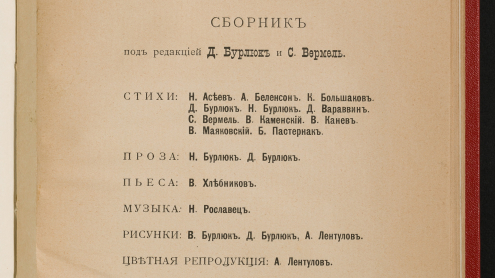

Vesennee kontragentstvo muz. Sbornik. Pod red. D. Burljuk i. S. Vermel‘. Moskva, 1915.

Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz

Signatur: 3 A 23594

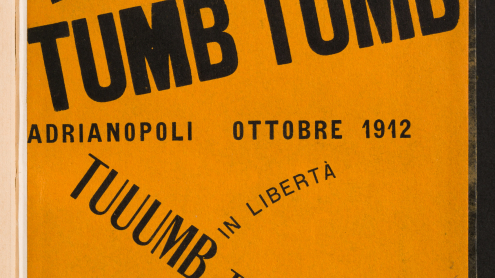

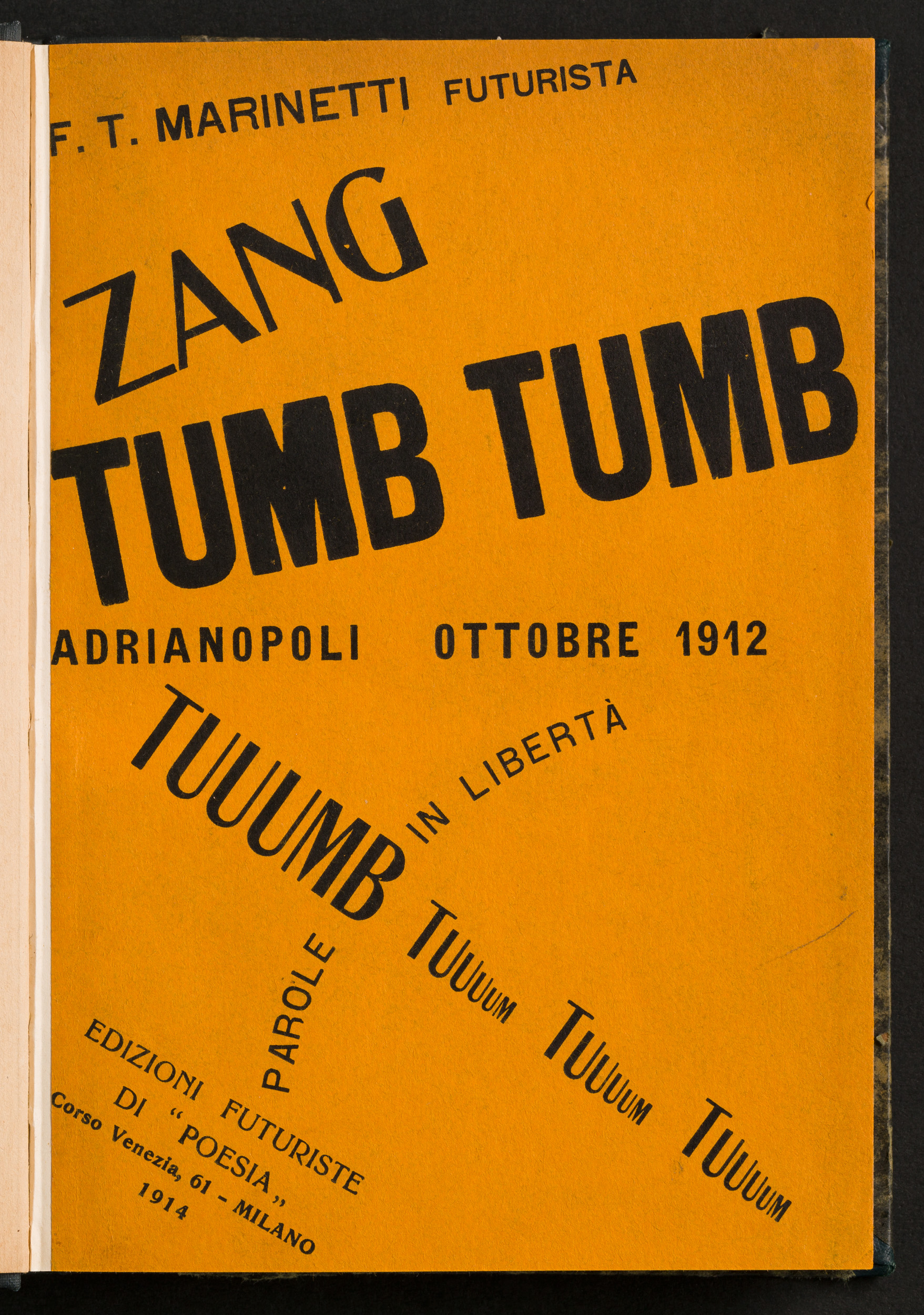

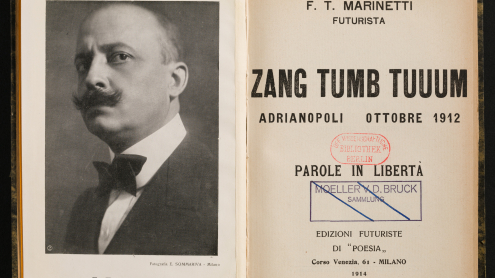

Marinetti, Filippo Tommaso

Zang tumb tuuum. Adrianopoli ottobre 1912. Parole in libertà. Milano, 1914.

Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Rara-Sammlung

Signatur: 19 ZZ 10374

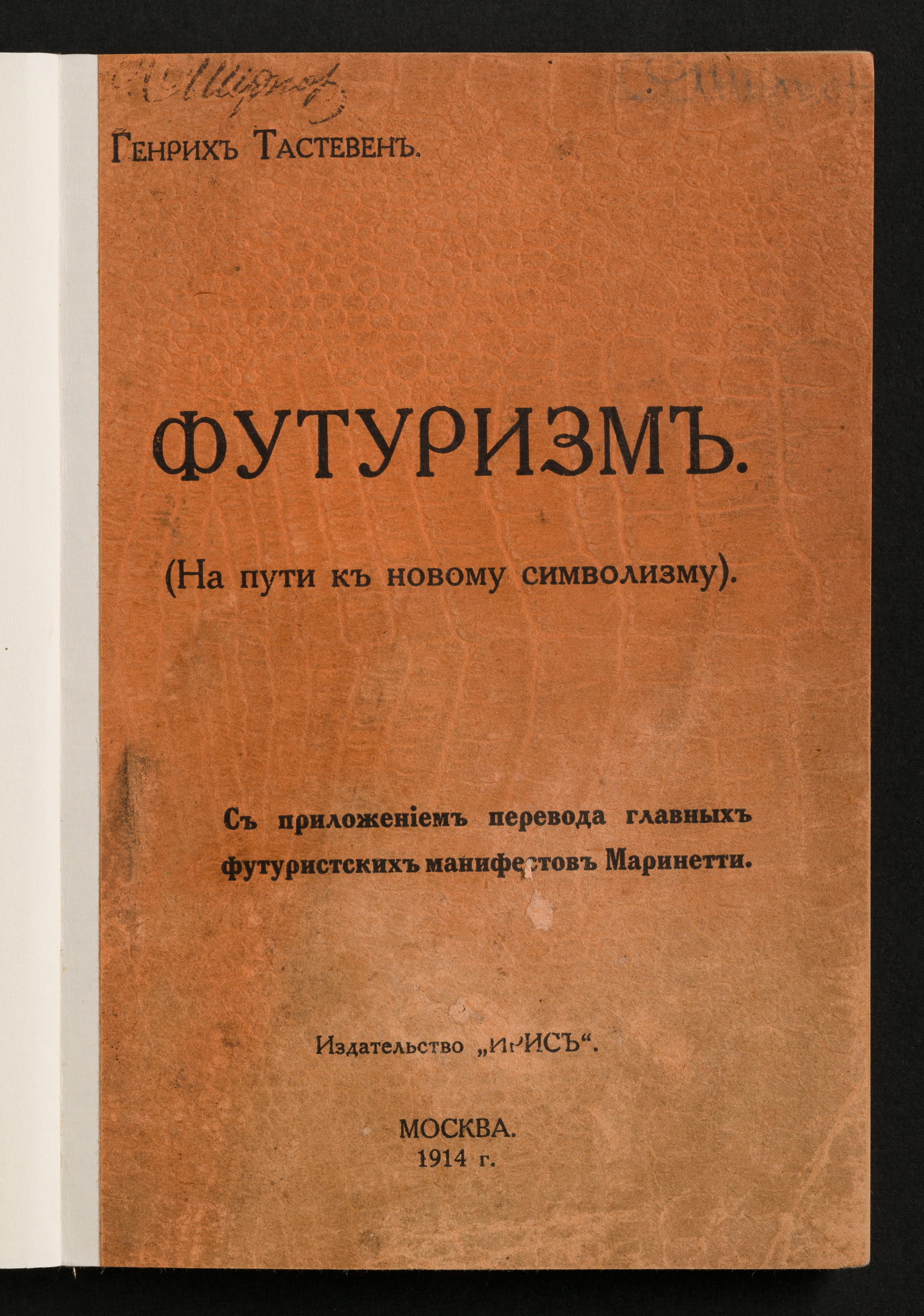

Tasteven, Genrich

Futurizm. (Na puti k novomu simvolizmu). S priloženiem perevoda glavnych futuristskich manifestov Marinetti. Moskva, 1914.

Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Rara-Sammlung

Signatur: 3 A 21418

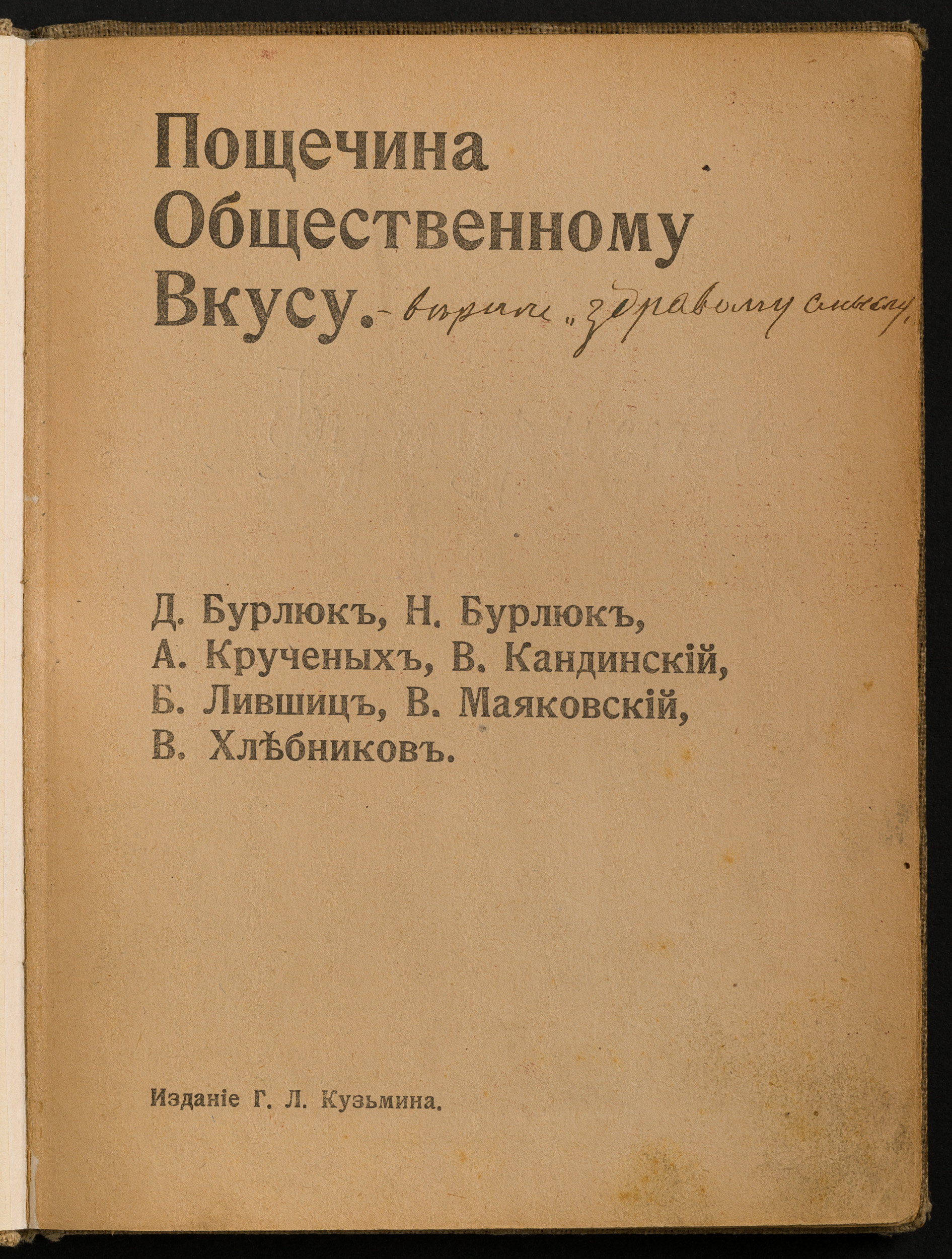

Burljuk, David Davidovič

Poščečina Obščestvennomu Vkusu. Moskva, 1912.

Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Rara-Sammlung

Signatur: 421373

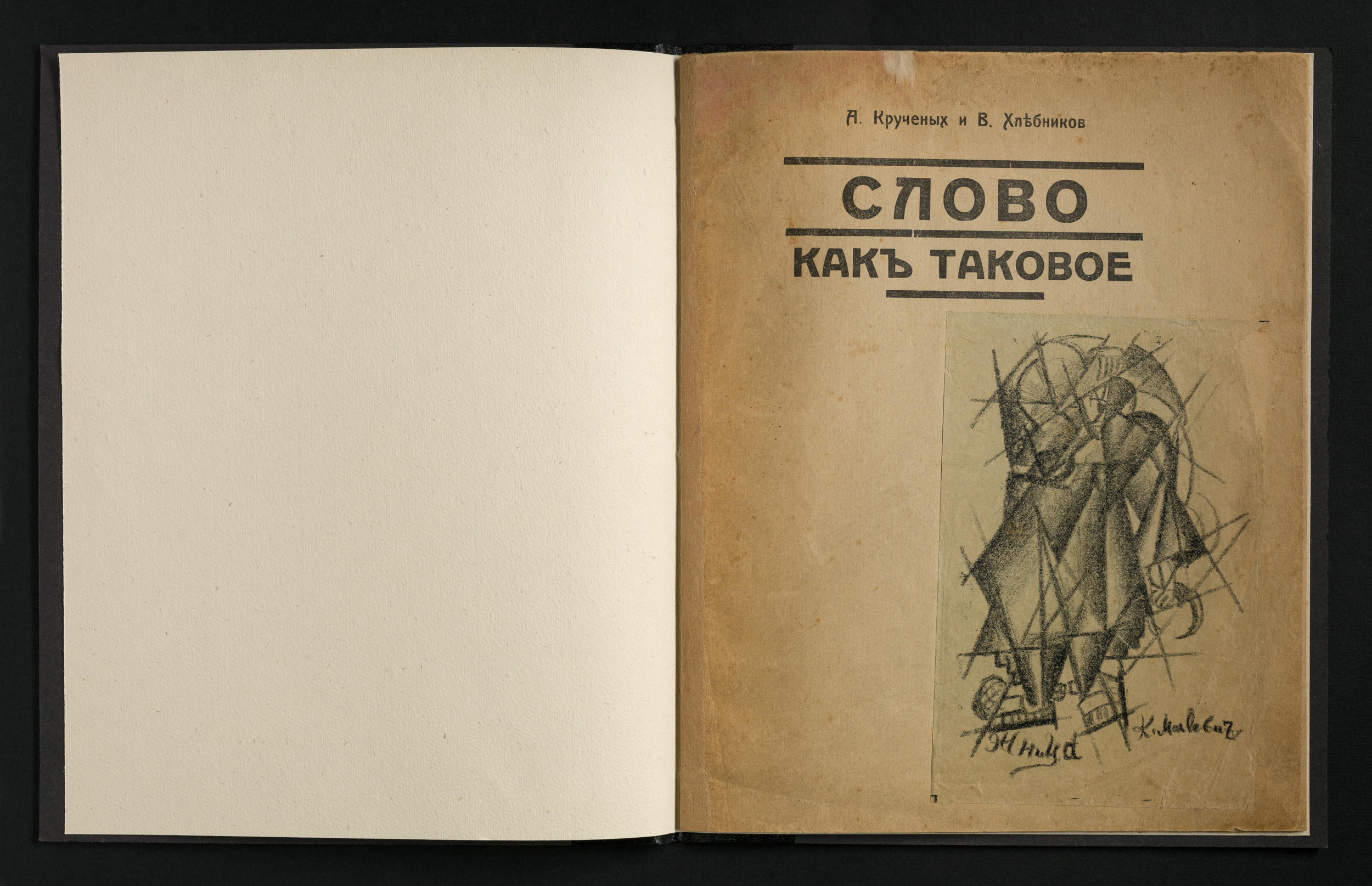

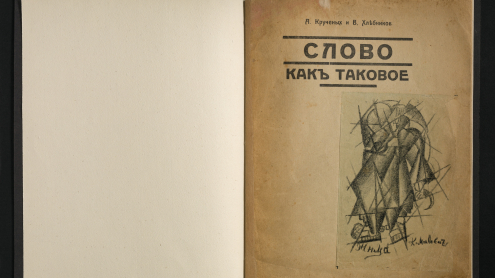

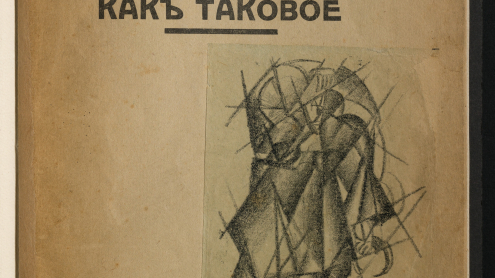

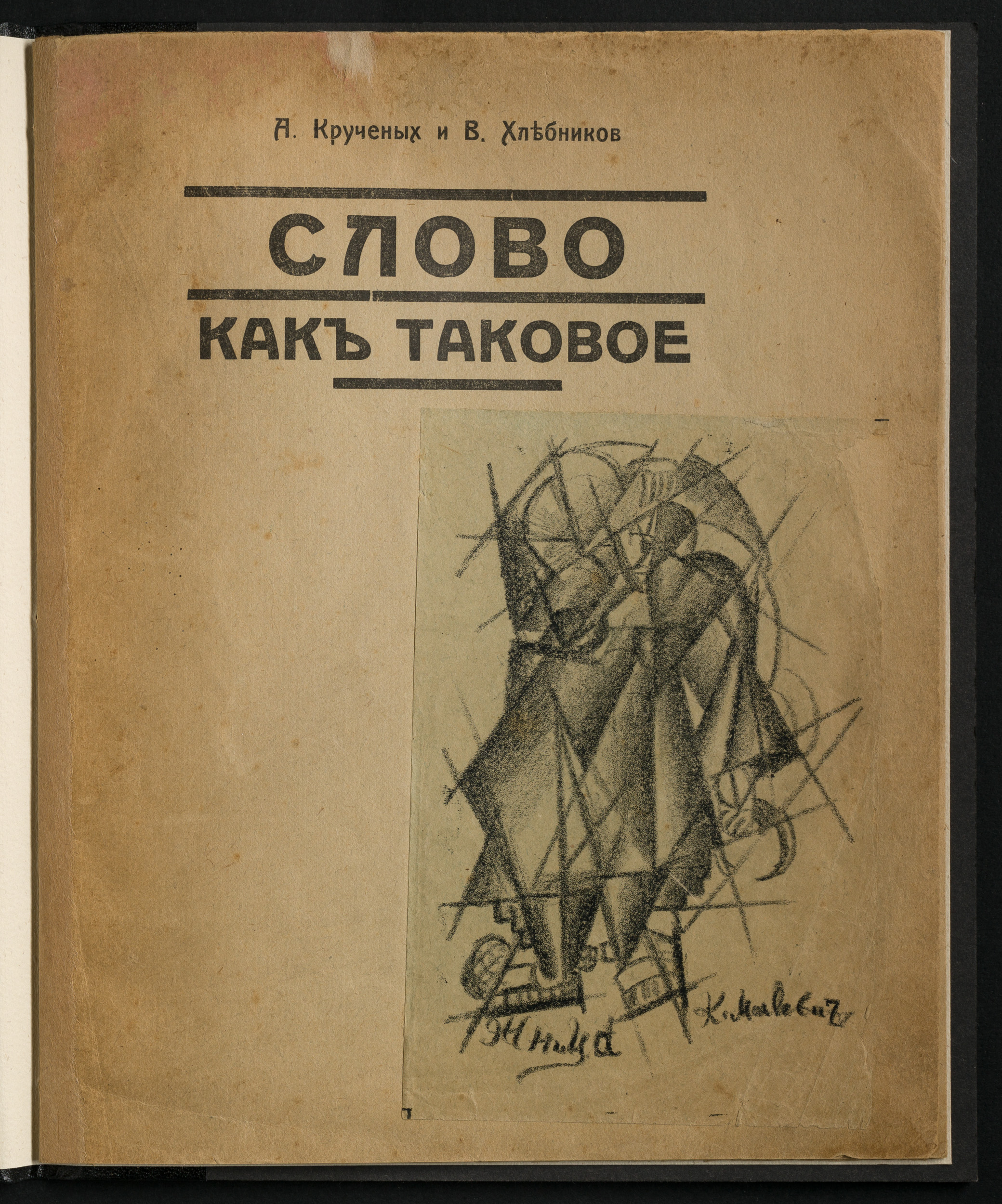

Kručenych, Aleksej Eliseevič; Chlebnikov, Velimir

Slovo kak takovoe. Moskva, ca. 1913.

Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Rara-Sammlung

Signatur: 46 MA 426

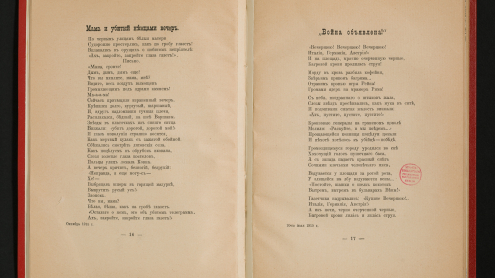

Vesennee kontragentstvo muz. Sbornik. Pod red. D. Burljuk i. S. Vermel‘. Moskva, 1915.

Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz

Signatur: 3 A 23594

David Burliuk edited the Futurist anthology The Spring Forwarding Agency of the Muses (Vesennee kontragentstvo muz) with the actor and poet Samuil Vermel’. Published in May 1915 in a huge run of 5000 copies, the anthology unites Moscow Futurists from what had been rival factions: the Hylaea Cubofuturists (Burliuk, Kamensky, Mayakovsky, Khlebnikov), Centrifuge (Aseyev, Pasternak), and the factionally polyamorous Konstantin Bolshakov. It also includes more marginal figures, such as Vermel’ himself, who wrote faux-Japanese tankas. The Kontragentstvo carries no manifestos and opens with Kamensky’s poems about aviation. The painter Aristarkh Lentulov did the cover.

Kručenych, Aleksej Eliseevič; Chlebnikov, Velimir

Slovo kak takovoe. Moskva, ca. 1913.

Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Rara-Sammlung

Signatur: 46 MA 426

Kruchenykh’s The Word as Such (Slovo kak takovoe) is one of the first theoretical declarations of Cubofuturist poetics. The text was composed possibly with some criticism by Khlebnikov, who is nonetheless listed as co-author. The cover features a drawing by Kazimir Malevich of a peasant woman reaping corn. Kruchenykh published the brochure in October 1913, as he, Malevich and Matiushin were planning the staging of his opera Victory over the Sun in St Petersburg. The Word as Such calls attention to the phonetics of the poetic text and argues for slowing down the act of reading by rendering the phonetic and metaphorical texture more difficult to consume. Kruchenykh draws a parallel between the breaking up of the object in Cubofuturist painting and the breaking up of the word in Cubofuturist poetry: “Futurist painters like to make use of parts of bodies, their cross sections, while Futurist poets use chopped-apart words, halfwords, and their fanciful clever combinations (transrational language).” The phrase “transrational language” (zaumnyi iazyk or, later, just zaum) refers to semantically indefinite “words” constructed for the sake of their sound, a Russian Futurist practice that anticipates Dada Lautgedichte.

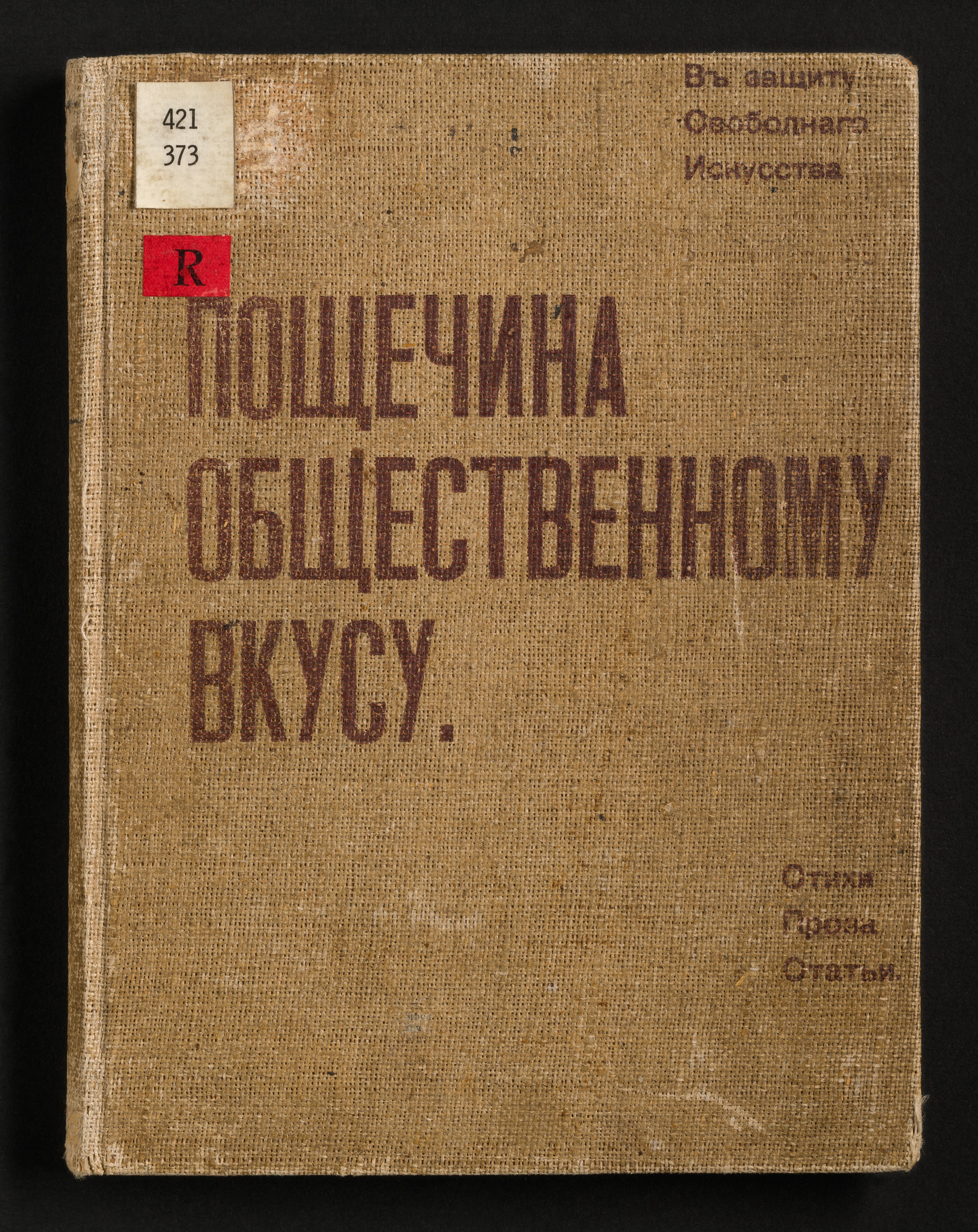

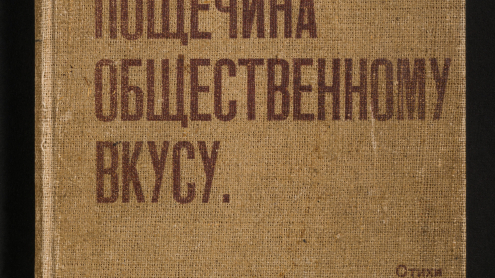

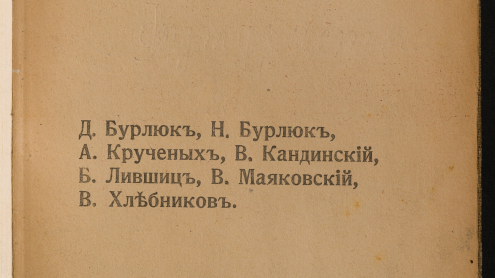

Burljuk, David Davidovič

Poščečina Obščestvennomu Vkusu. Moskva, 1912.

Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Rara-Sammlung

Signatur: 421373

A Slap in the Face of Public Taste (Poshchechina obshchestvennomu vkusu), released in Moscow in December 1912, was the first anthology of the Hylaea group, also known as the Cubofuturists. It is also the first anthology to include a manifesto, a genre associated with the Italian Futurists. The manifesto announces the Futurist poetics of lexical innovation (neologisms) and famously calls for Pushkin, Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy and other classics to be “thrown… off the steamship of modernity.” The signers would be reprimanded for this gesture, which aped Marinetti’s call to burn museums and libraries, to the end of their days. A Slap includes work by the Burliuk brothers and Khlebnikov, veterans of the 1910 collection Critics Creel (Sadok sudei), as well as the powerful newcomers Mayakovsky, Kruchenykh and Benedict Livshits. Kamensky was not included because he was taking it easy after crashing his plane during a show flight in Poland. Four texts from Kandinsky’s Klänge were included without permission. In the theory section, Burliuk’s essay on Cubism introduces the concepts of sdvig (dislocation) and faktura (texture), while Khlebnikov gives many examples of the coinage of the new words. The burlap cover of A Slap in the Face of Public Taste is a slap in the face of public taste.

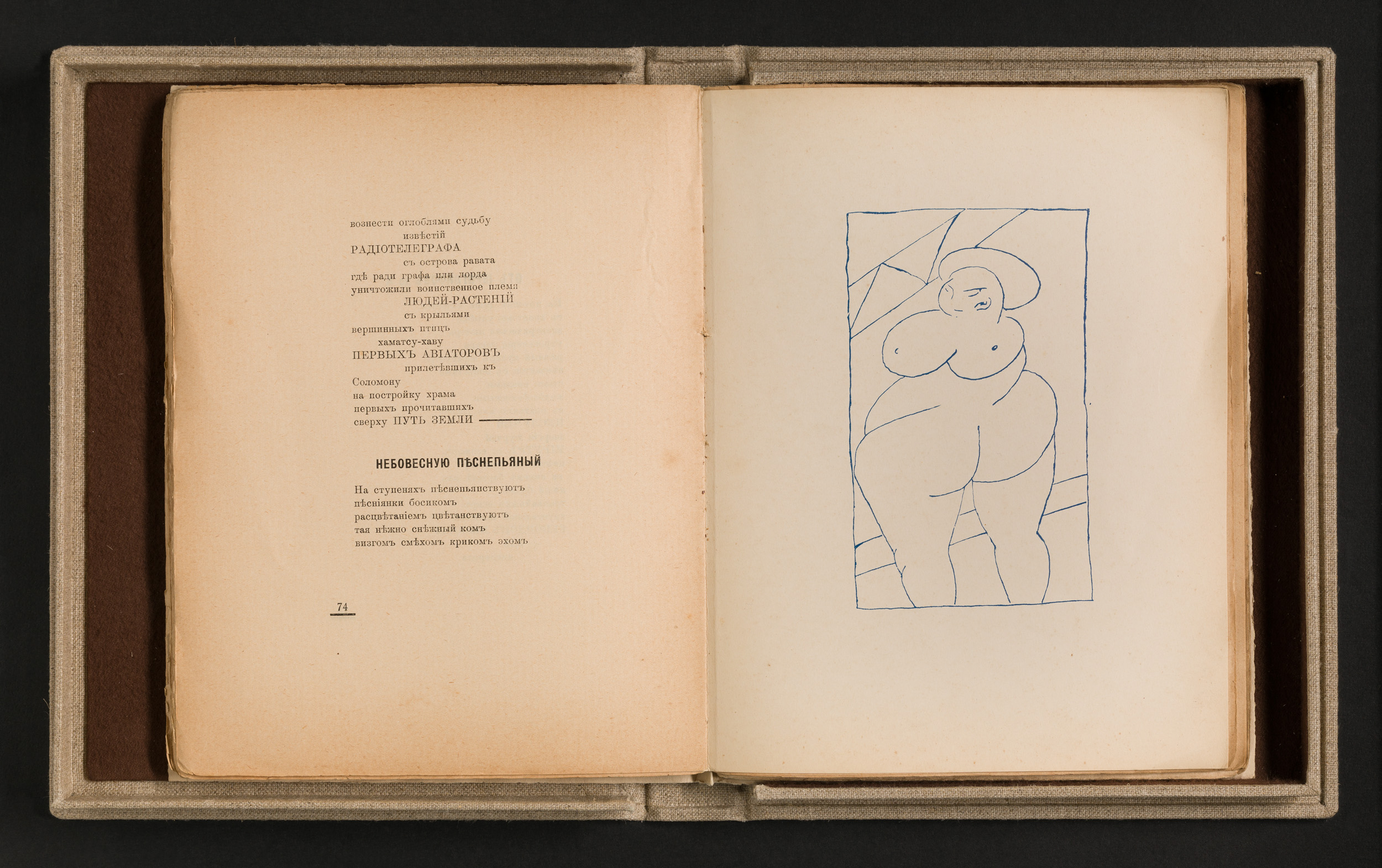

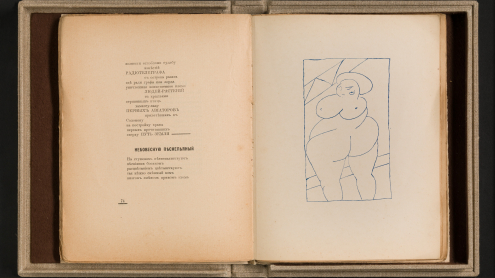

Dochlaja luna. Futuristy Konstantin Bol’šakov, Burljuki: David, Vladimir, Nikolaj, Vasilij Kamenskij, A. Kručenych, Benedikt Livšic, Vladimir Majakovsij, Viktor Chlěbnikov, Vadim Šeršenevič. Stichi, proza, stat’i, risunki, oforty. Izd. 2., dop. Moskva, 1914.

Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Rara-Sammlung

Signatur: 3 A 6201

The first edition of Dropping Dead Moon (Dokhlaya luna) came out in the fall of 1913. Kamensky is not in it, because he had not yet joined the Cubofuturists. The second, substantially expanded edition, shown here, was published in the late spring of 1914. It includes not only poems by Kamensky, but also those by members of other Futurist groups, who had collaborated with the Cubofuturists during the winter of 1913-14 (Shershenevich, Bolshakov, Severyanin). The anthology thus suggests that the period of acute rivalry between factions, characteristic of 1912-13, is at an end. Dropping Dead Moon opens with “The Liberation of the Word,” a theoretical essay in which Benedict Livshits argues that words in a poem must be “liberated” from meanings and instead follow phonetic, prosodic and compositional laws that affect them as material objects. While Livshits’s title alludes to Marinetti’s new poetic language of parole-in-libertà, the liberation advocated by Marinetti affects syntax but not semantics. The nude on the facing page by David Burliuk exemplifies his early idea of the sdvig, or dislocated construction, since its body parts are moved from their natural positions.

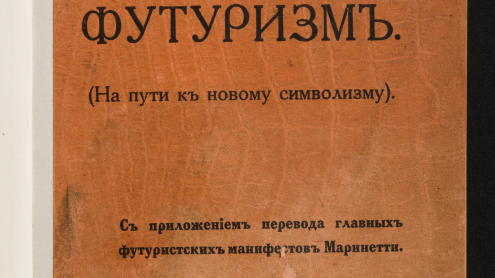

Tasteven, Genrich

Futurizm. (Na puti k novomu simvolizmu). S priloženiem perevoda glavnych futuristskich manifestov Marinetti. Moskva, 1914.

Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Rara-Sammlung

Signatur: 3 A 21418

The critic Henri Tastevin organized Marinetti’s visit to Moscow and St Petersburg between January 26 and February 17, 1914 (according to the Julian calendar used in Russia before 1918). Marinetti delivered six lectures in total. He spoke in French and was ecstatically welcomed by the Russian press as a cultured, wealthy European and an authentic Futurist, unlike his Russian imitators who were just bohemian crazies. Naturally, the bohemian crazies denounced Marinetti and denied owing him anything but their name. Khlebnikov and Livshits tried to disrupt his lecture in St Petersburg. Burliuk and Mayakovsky tried to debate him in Moscow, but the moderator would not let them reply in Russian, and their French was not good enough. A near-riot ensued. Tastevin’s book was printed in expectation of Marinetti’s visit, and the Italian Futurist received an advance copy of it upon arrival in Moscow. Tastevin argues that both Futurisms, and especially the more radical Russian version, are extreme developments of the ideas of Mallarmé.

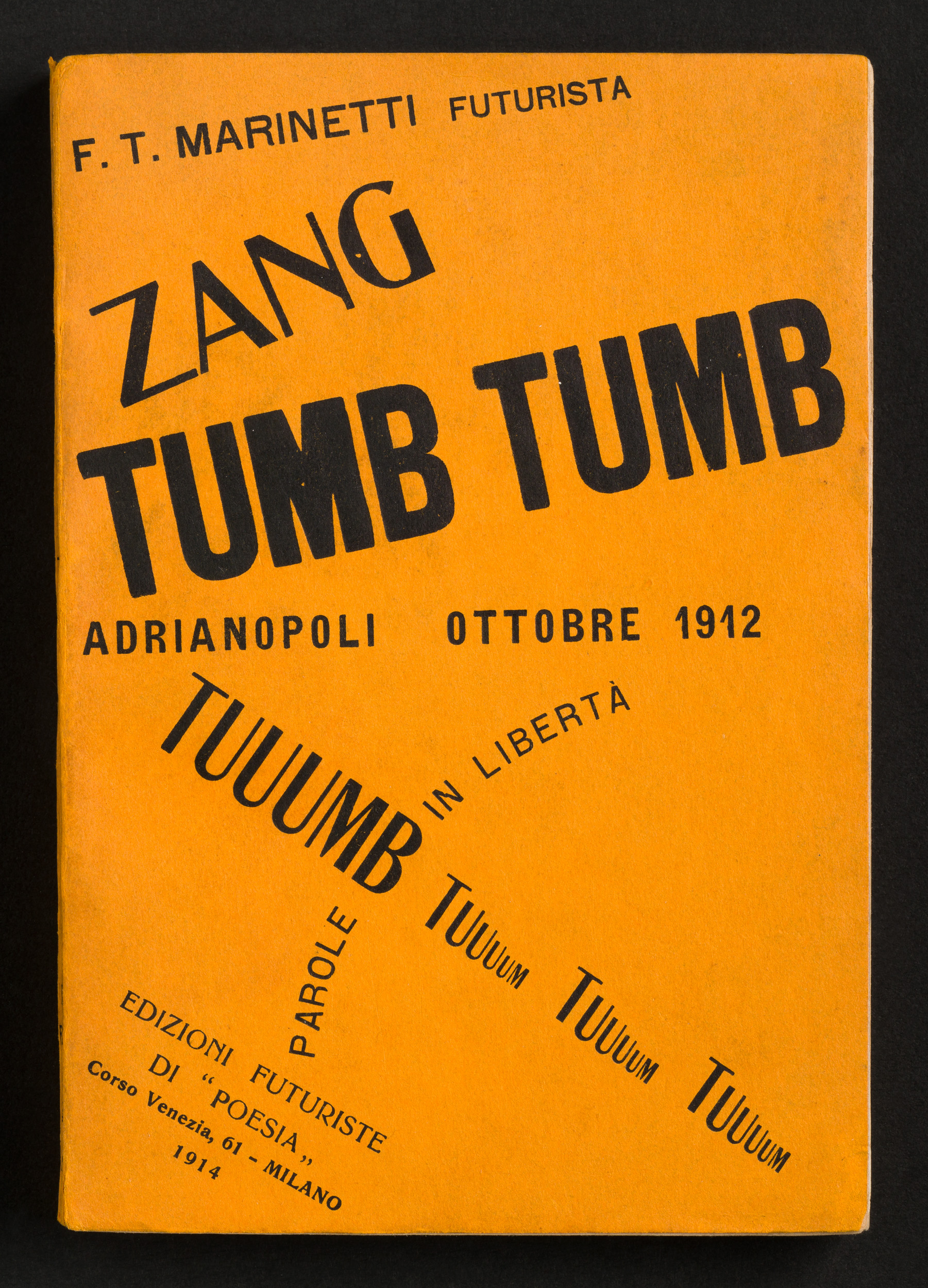

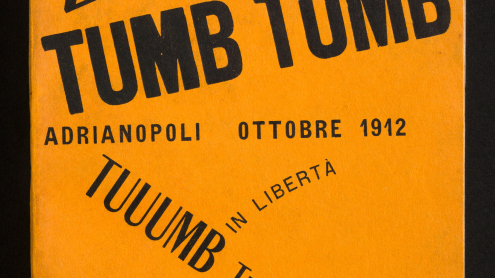

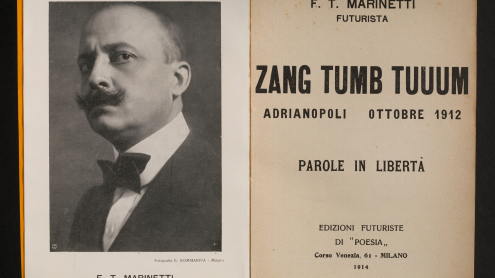

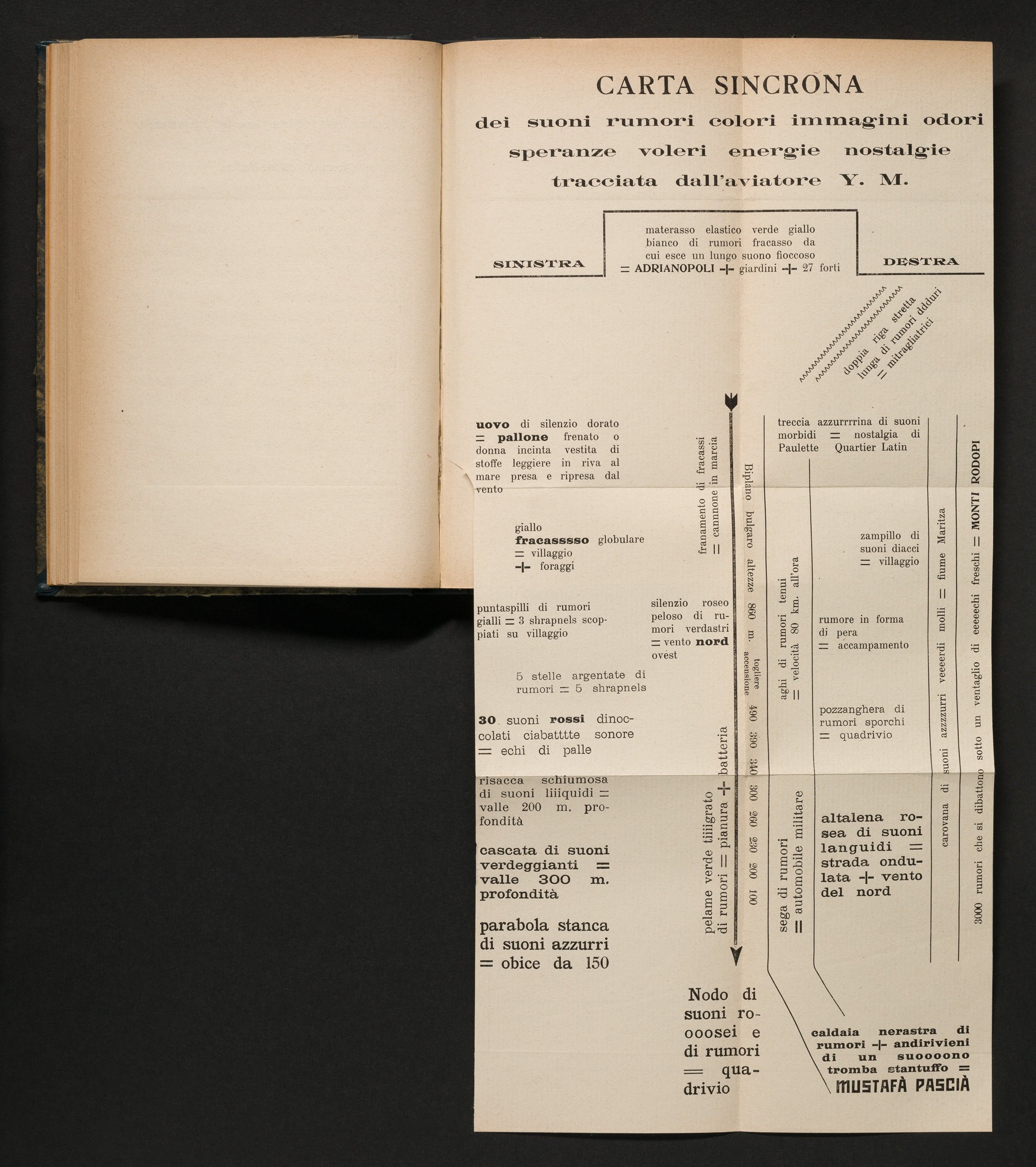

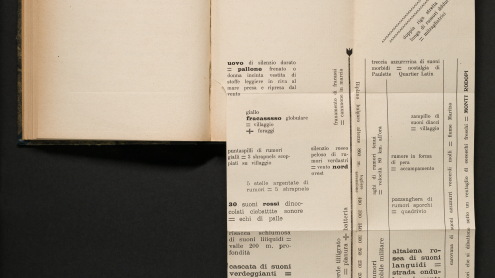

Marinetti, Filippo Tommaso

Zang tumb tuuum. Adrianopoli ottobre 1912. Parole in libertà. Milano, 1914.

Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Rara-Sammlung

Signatur: 19 ZZ 10374

Marinetti’s Zang Tumb Tuuum, published in Milan in March 1914, is the first book-length example of the new poetic language of Italian Futurism: parole-in-libertà, or words-in-freedom. It tells of the siege of Ottoman Adrianople (Edirne) by Bulgarian and Serbian armies during the First Balkan War. Marinetti saw the modern war of mass armies and industrial machinery to be as suitable a subject for Futurist writing as the siege of Troy was for Homer’s world of heroic individuals. This foldout displays the perceptions, sensations and memories of a Bulgarian aviator flying over Adrianople. Far-flung poetic analogies, given without any syntax except the equal sign (the capacity for such analogies is called “wireless imagination”), represent what the aviator sees, feels and thinks. The absence of distinction between the outside and the inside, perception and memory, constitutes one aspect of what Italian Futurists called “simultaneity.” Another aspect of simultaneity is that, as in Kamensky’s ferroconcrete poems but unlike most of Zang Tumb Tuuum, the text is given all at once, without any necessary reading order but rather as a picture composed of words and typographic signs, whose borders coincide with those of a page. It used to be thought that Tango with Cows might have been inspired by Zang Tumb Tuuum, but Kamensky’s poems were composed and even set weeks before he could have seen Marinetti’s novel.

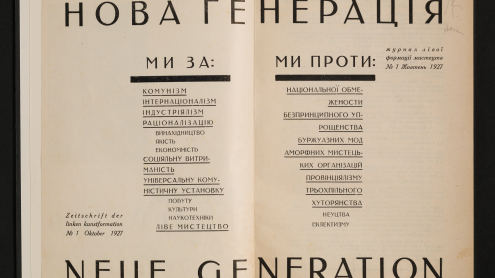

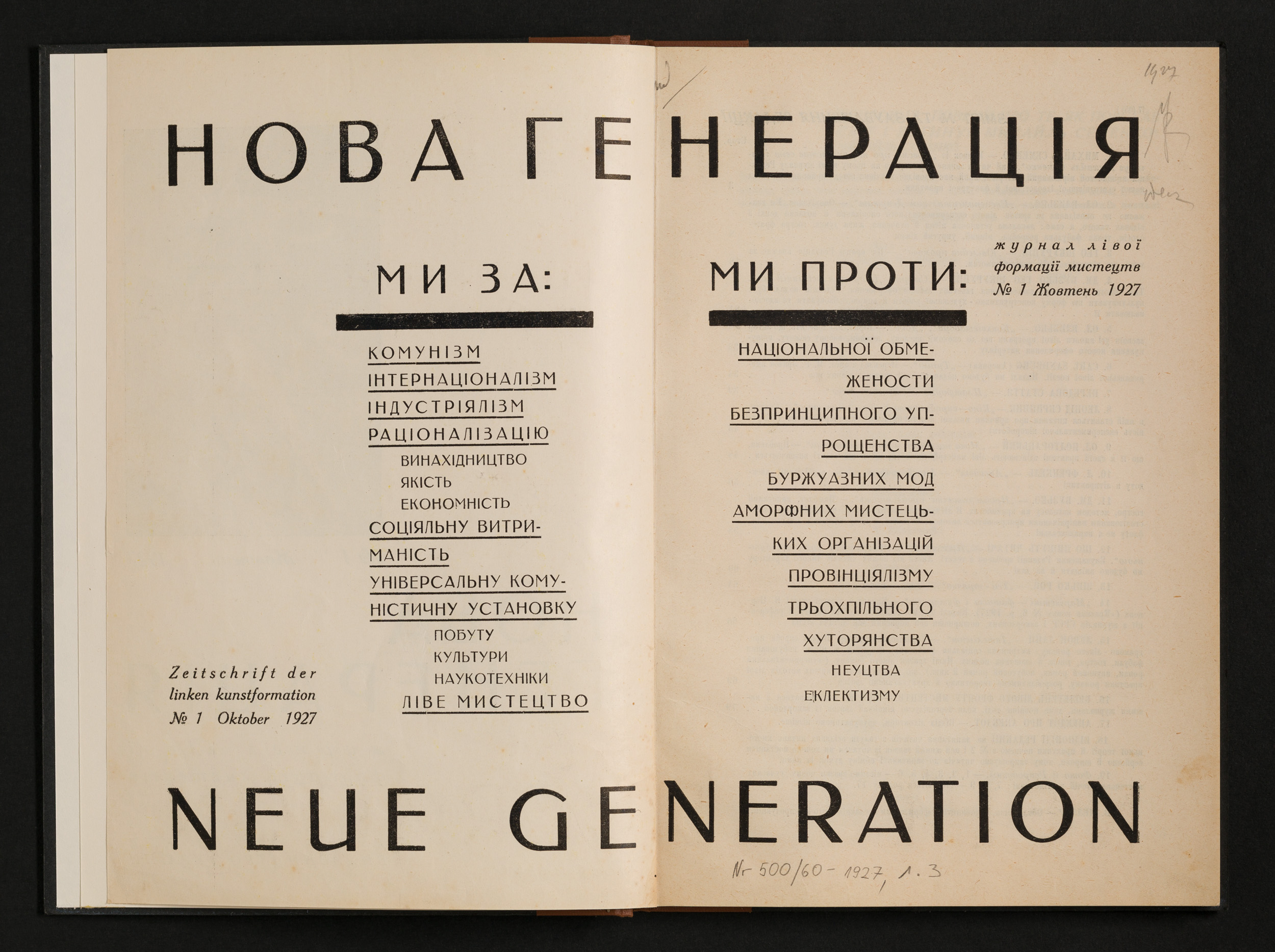

Nova generacija. Žurnal livoï formaciï mystectv. Charkiv, 1927.

Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz

Signatur: Nr 500/60-1927,1/3(N=2)

New Generation (Nova generatsiia) was the monthly of Ukrainian Futurists published in Kharkiv from October 1927 to December 1930. Its founder and editor-in-chief, the poet Mykhail’ Semenko, had pioneered Ukrainian Kverofuturism (from the Latin quaero, to seek) already in 1914. In the early 1920s, Semenko, Geo Shkurupii and others in their group developed a movement they called “Panfuturism” to emphasize its synthesis of all avant-garde techniques and ideas. Positioning themselves as true Communists in the post-revolutionary situation, and highly committed to the project of the making of the new world for the new man, the Panfuturists argued that Great Art of the past—the irrational, individualist art of the bourgeoisie with its mystifying cult of genius—was at an end. It would be superseded by rational, scientific, process-based and technologically savvy new art which would permeate everyday life rather than be confined to museums and libraries. This position put the Panfuturists in conflict with the Party’s growing preference for the resuscitation of bourgeois aesthetics and artworks for proletarian use. When Semenko’s group founded New Generation as their first regular periodical in 1927, the term “Panfuturism” did not appear in the first issue. Instead, the journal aimed to promote “the theory and practice of the Left Front of the Arts,” a motto that positions the magazine politically and aesthetically, corresponding to the motto of the Russian journal “Novyi LEF” (meaning “New Left Front of the Arts”), edited by Mayakovsky. On the constructivist-style frontispiece, New Generation declares itself to be in favor of “Communism, Internationalism, Industrialism, Economic Rationalization (inventiveness, quality, austerity),” and “The Application of Universal Communist Principles to Everyday Life, Culture, Science and Technology, and Avantgarde Art.” By contrast, it declares itself in opposition to the more traditionalist groups on the Ukrainian literary and intellectual scene, which it regarded as affected by “National Narrow-Mindedness, Unprincipled Simplification, Bourgeois Fashions… Provincialism, Redneckery, Semiliteracy, Eclecticism.” Multilingual and cosmopolitan, New Generation envisioned Ukraine as a modern nation, unhampered by past traditions. It saw itself as a full-fledged participant in the European and international avant-garde movement, with no need for Russian intermediaries. Called upon to repent for its independence in 1930, New Generation resisted and was forced to fold. Many of the journal’s staff members, including Semenko and Geo Shkurupii, were shot in the purge of 1937.

Taking the initial number of Nova generacija as a starting point, Dr. Galina Babak (Masaryk Institute and Archives of the Czech Academy of Sciences), Prof. Susanne Frank (Eastern Slavic Literatures and Cultures, Humbolt-Universität zu Berlin) and poet Eugene Ostashevsky talk about Ukrainian futurism and its resonances, about concepts of nationality and internationalisation in an Avant-Garde context.

Futurism and Popular Culture

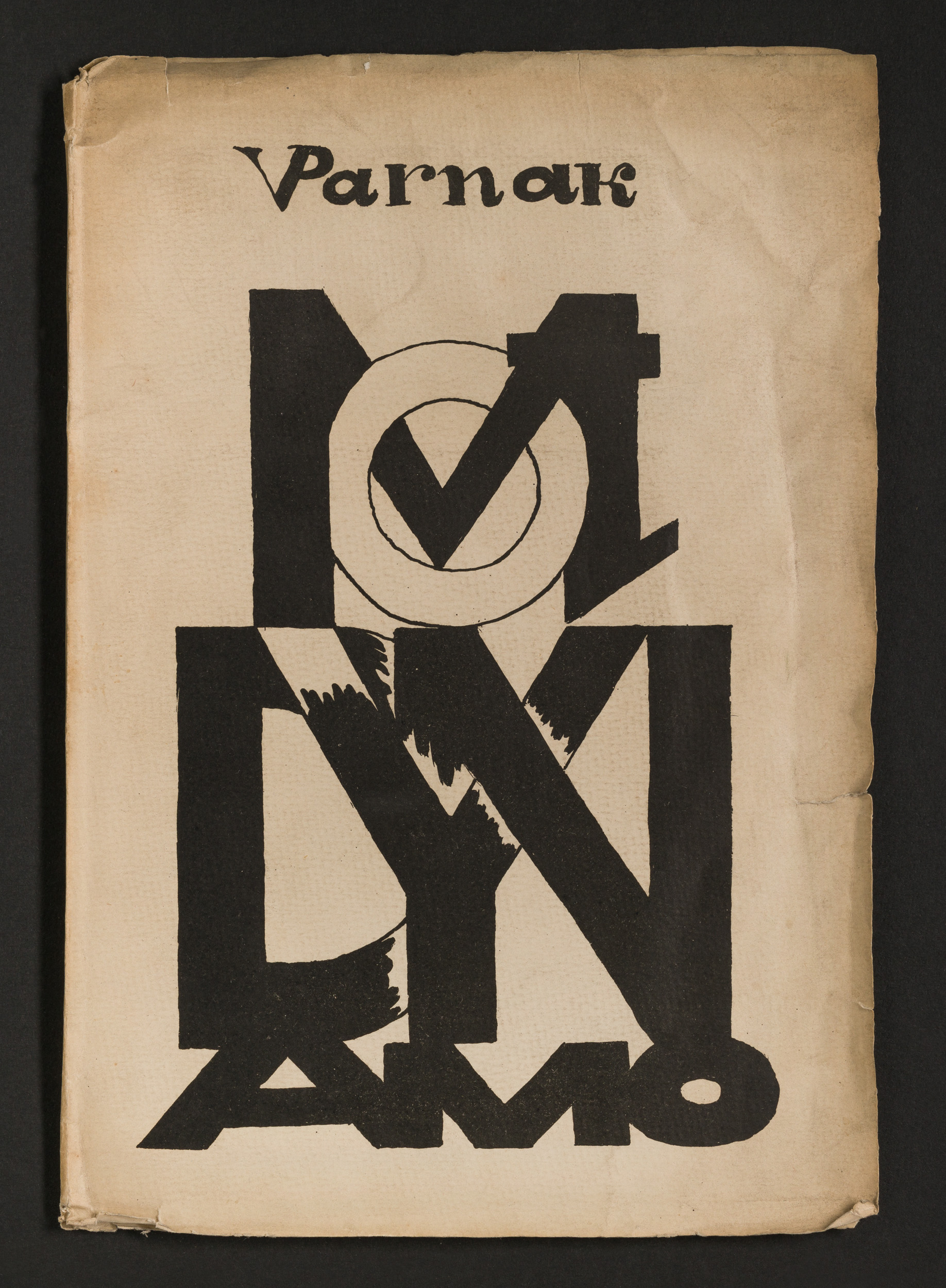

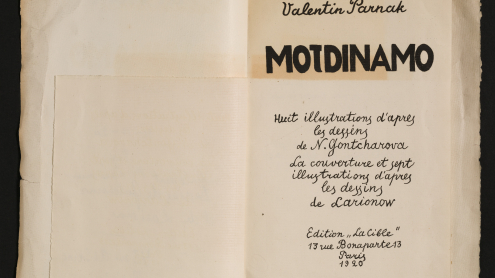

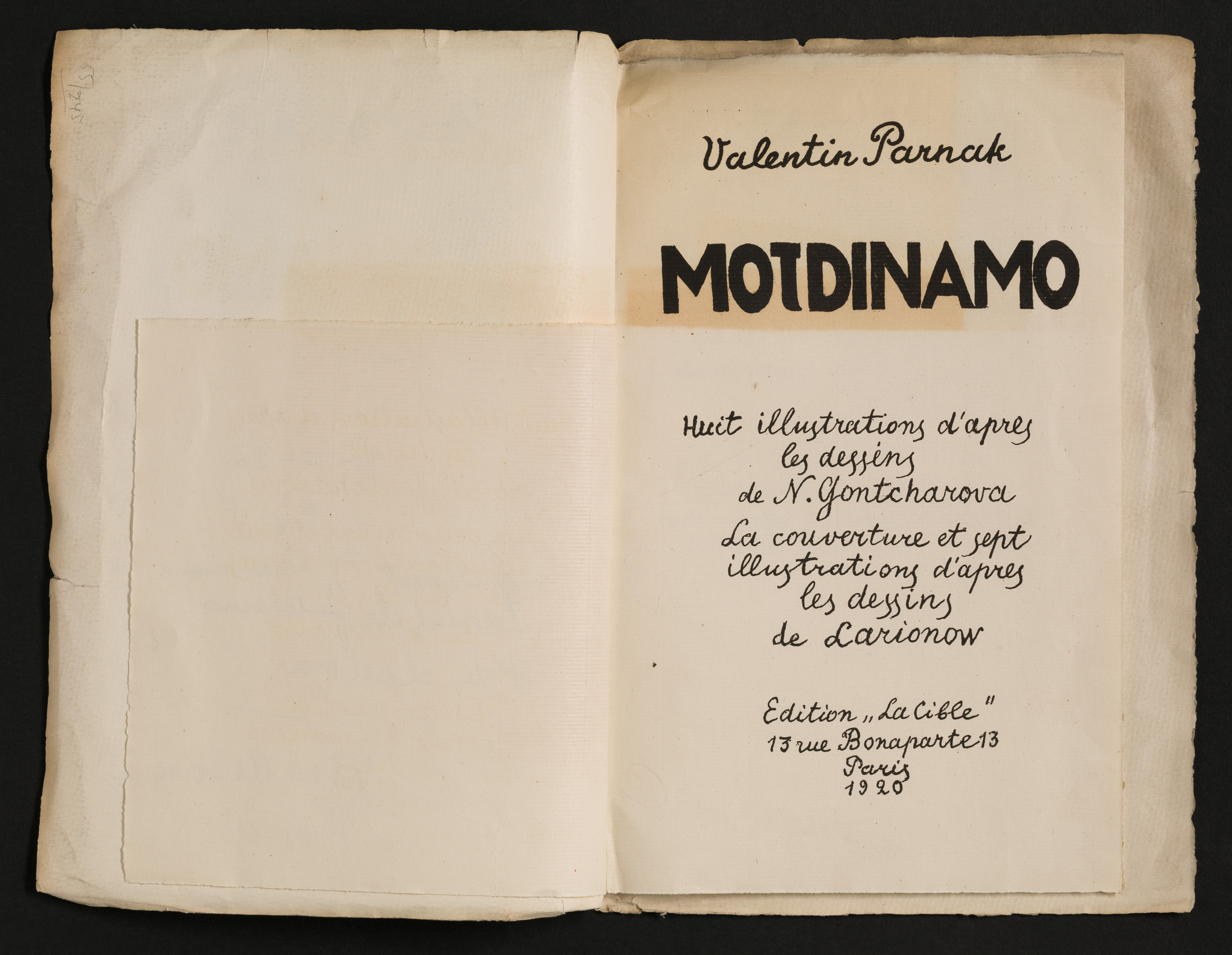

Parnach, Valentin Jakovlevič

Motdinamo. 8 ill. d’après les dessins de N. Gontcharova. La couverture et 7 ill. d’après les dessins de Larionow. Paris, 1920.

Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Rara-Sammlung

Signatur: 4” 19 ZZ 10248

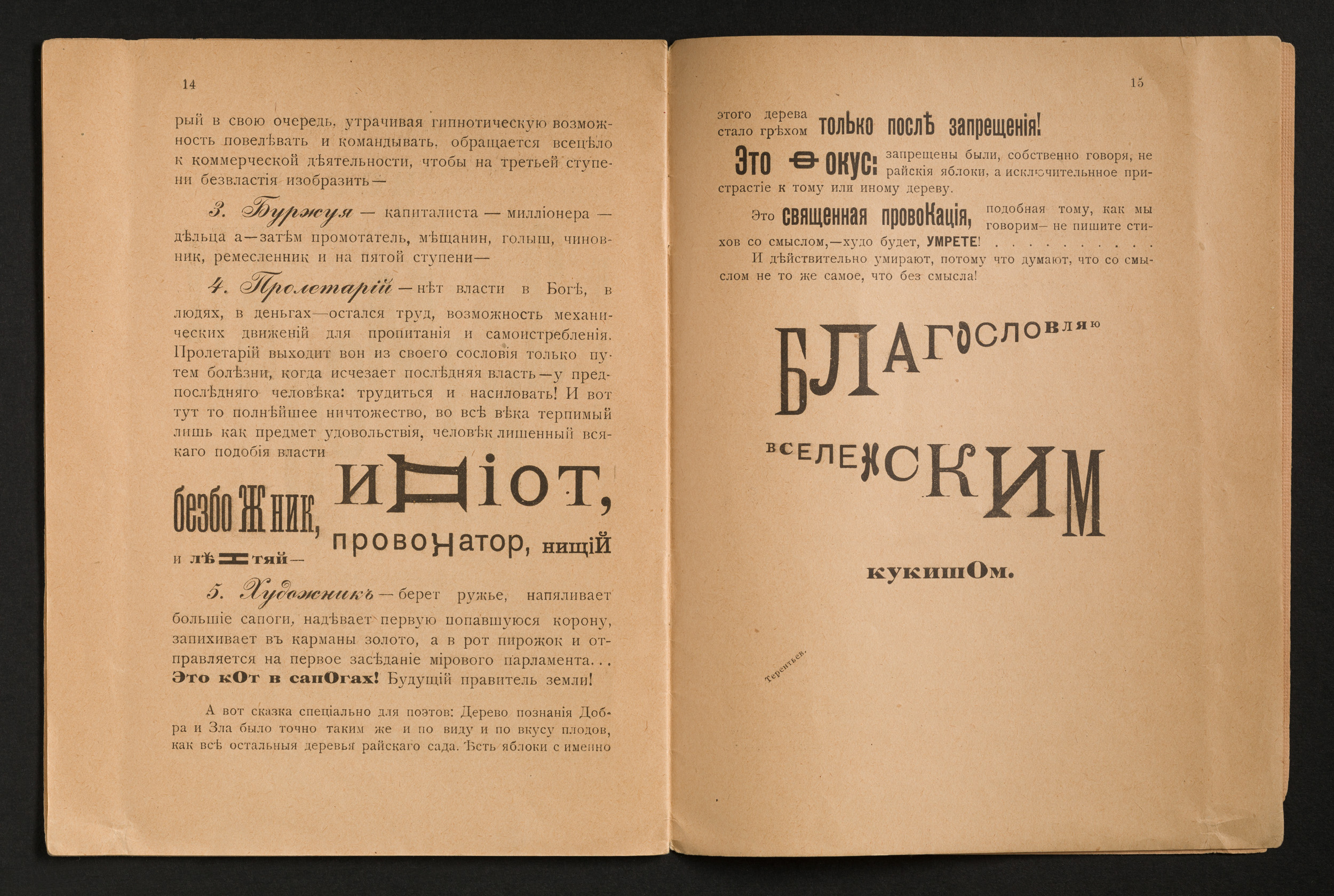

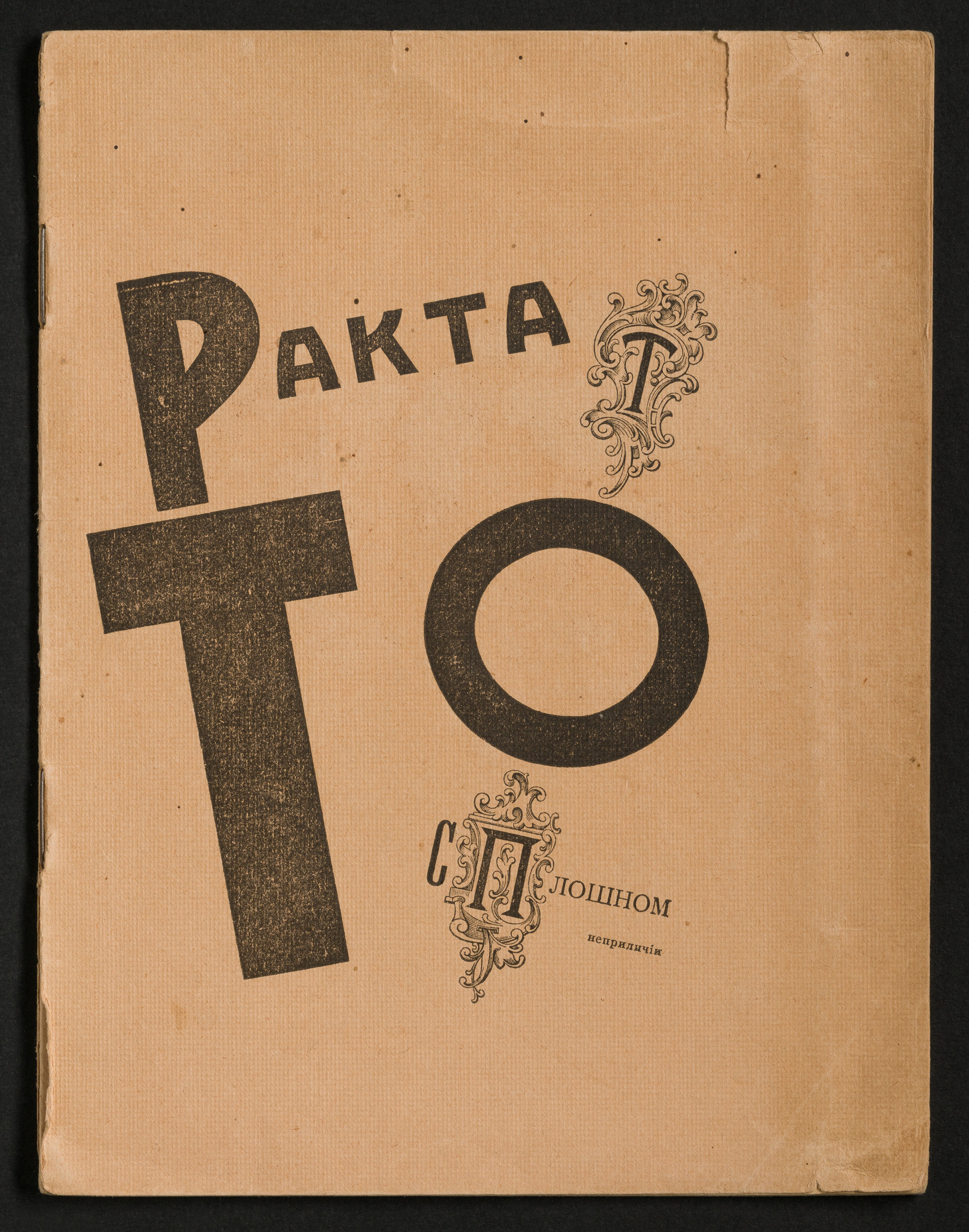

Terentʹev, Igorʹ Gerasimovič

Traktat o splošnom nepriličii. Tiflis, 1919.

Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Rara-Sammlung

Signatur: 3 A 170565

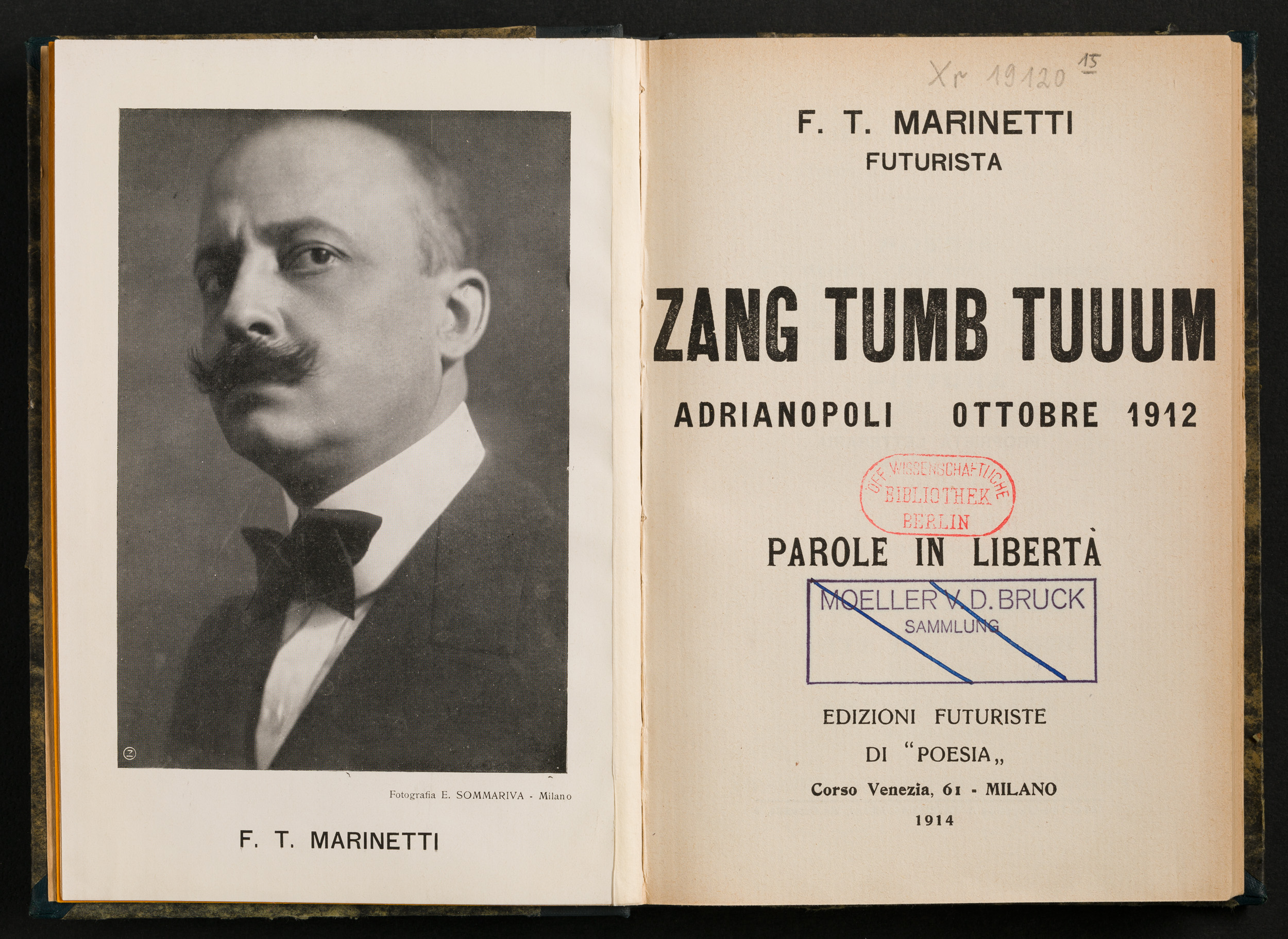

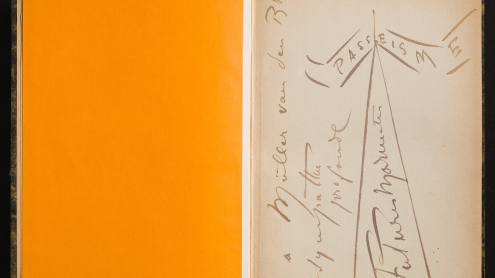

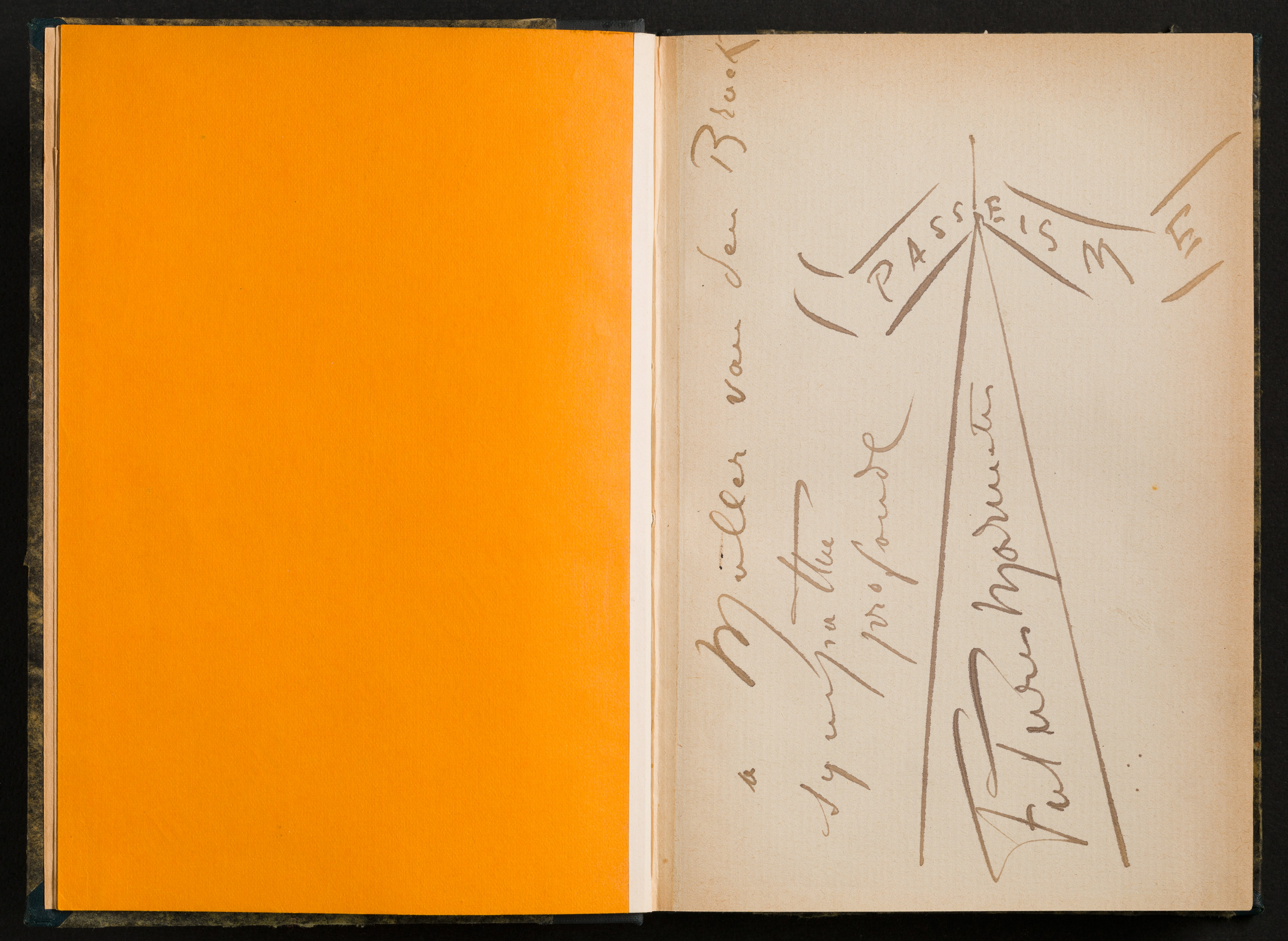

Marinetti, Filippo Tommaso

Zang tumb tuuum. Adrianopoli ottobre 1912. Parole in libertà. Milano, 1914.

Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Sammlung Künstlerische Drucke

Signatur: Xr 19120<15>

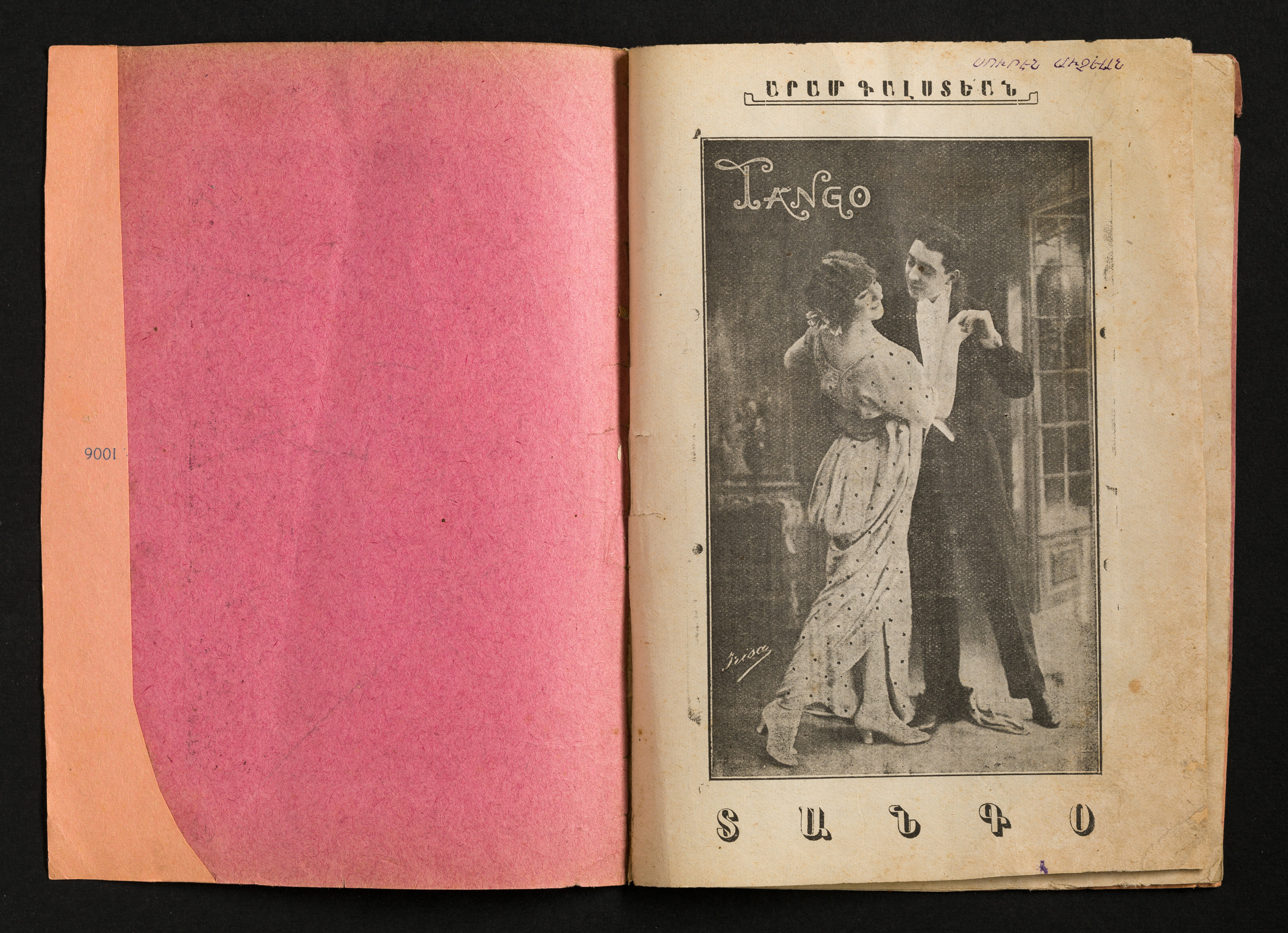

Galstean, Aram

Tango. Tiflis, ca. 1914.

Privatsammlung

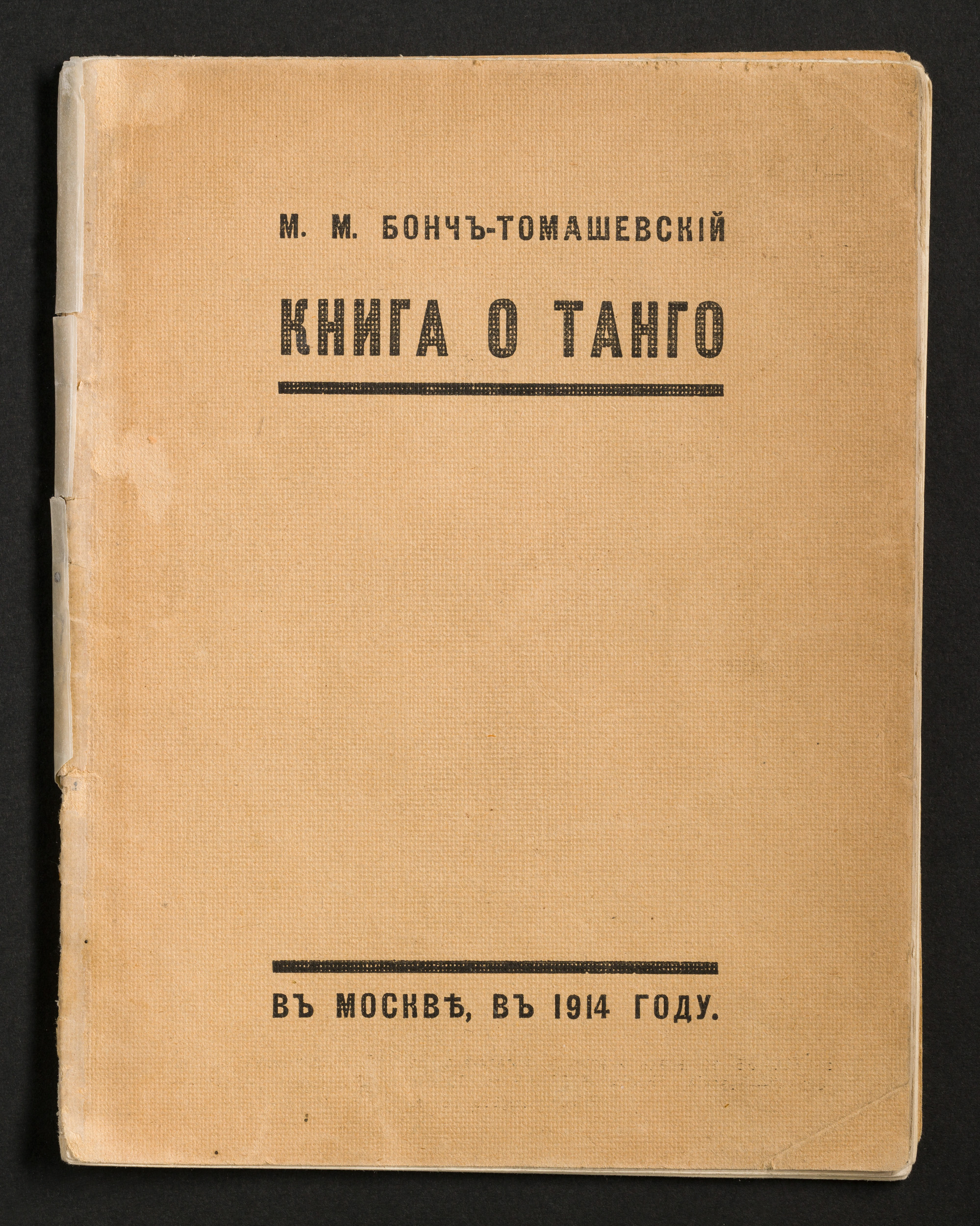

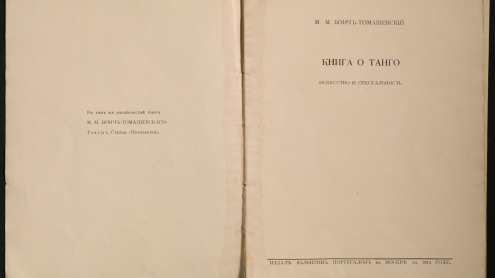

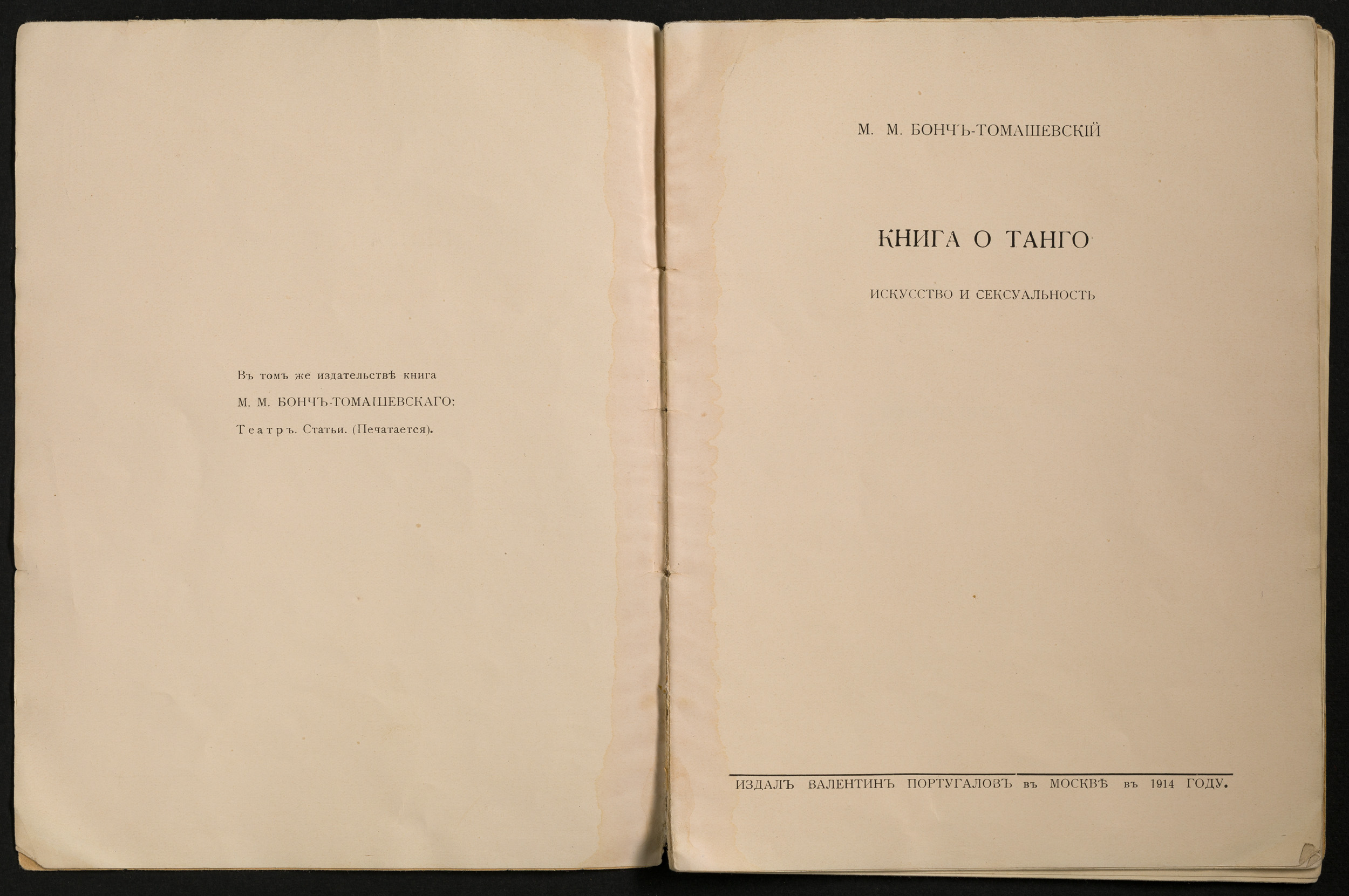

Bonc-Tomaševskij, Michail Michajlovič

Kniga o tango. Iskusstvo i seksual’nost‘. Moskva, 1914.

Privatsammlung

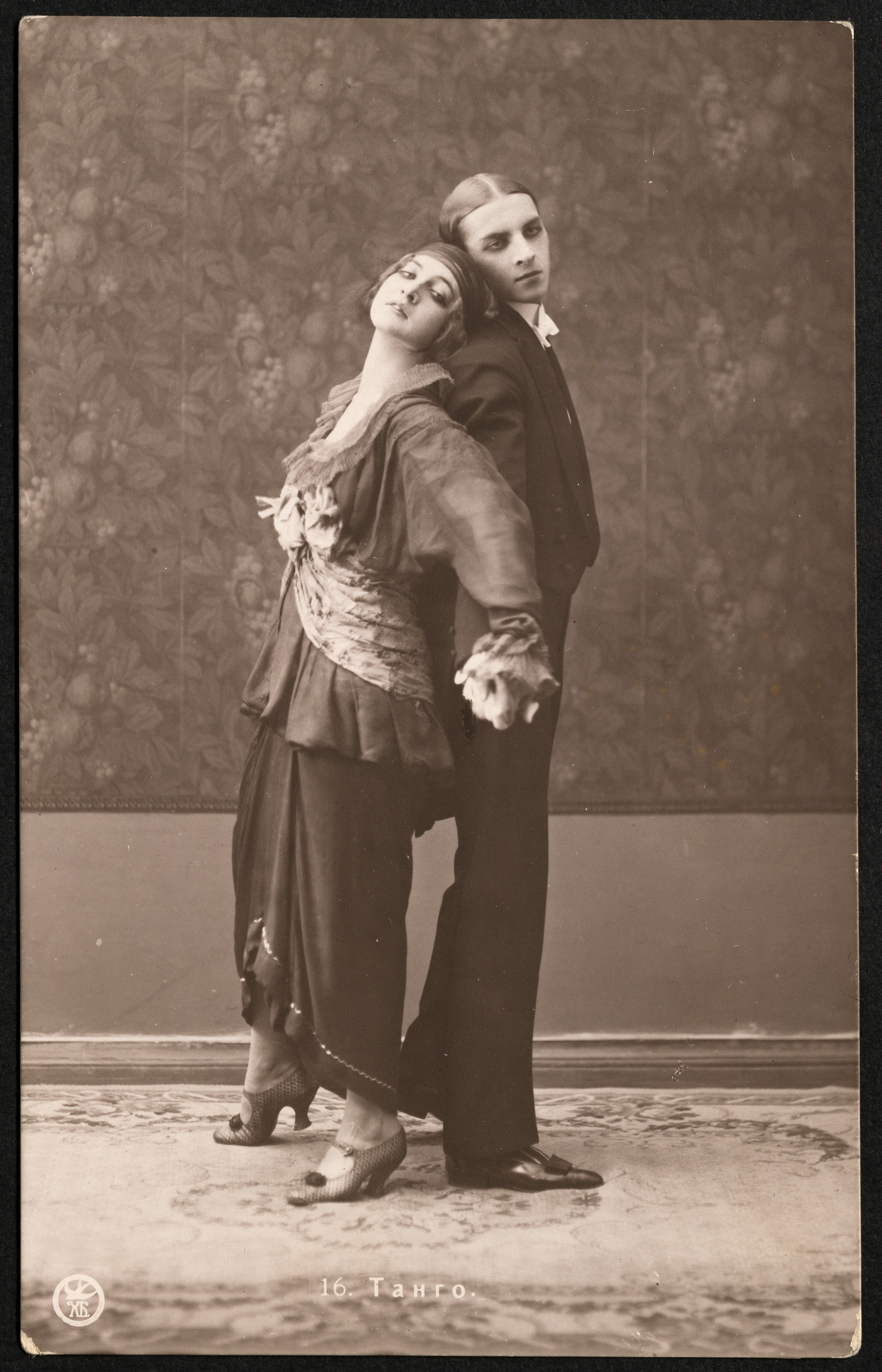

Elsa Krüger und Wally tanzen Tango.

Postkarten von D. Chromov and M. Bachrach. Moskva, 1914.

Privatsammlung

Marinetti, Filippo Tommaso

Manifesto tecnico della letteratura futurista. Milano, 1912.

(Manifesti del Movimento Futurista, 10)

Privatsammlung

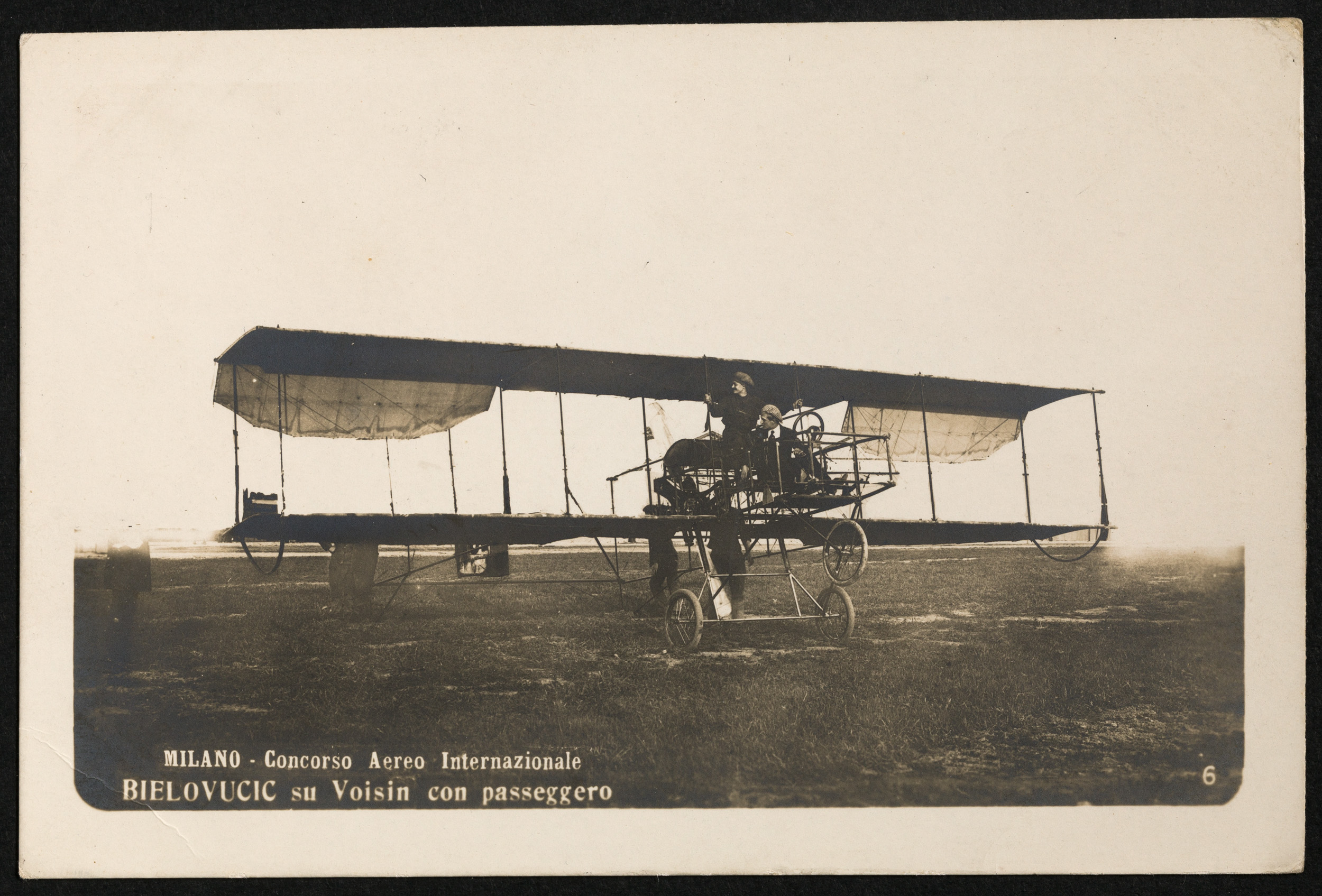

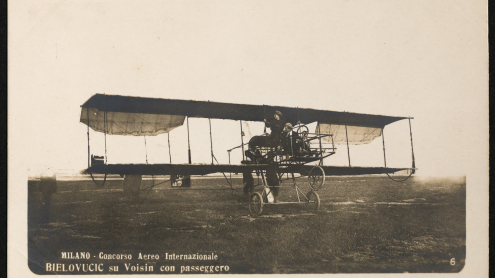

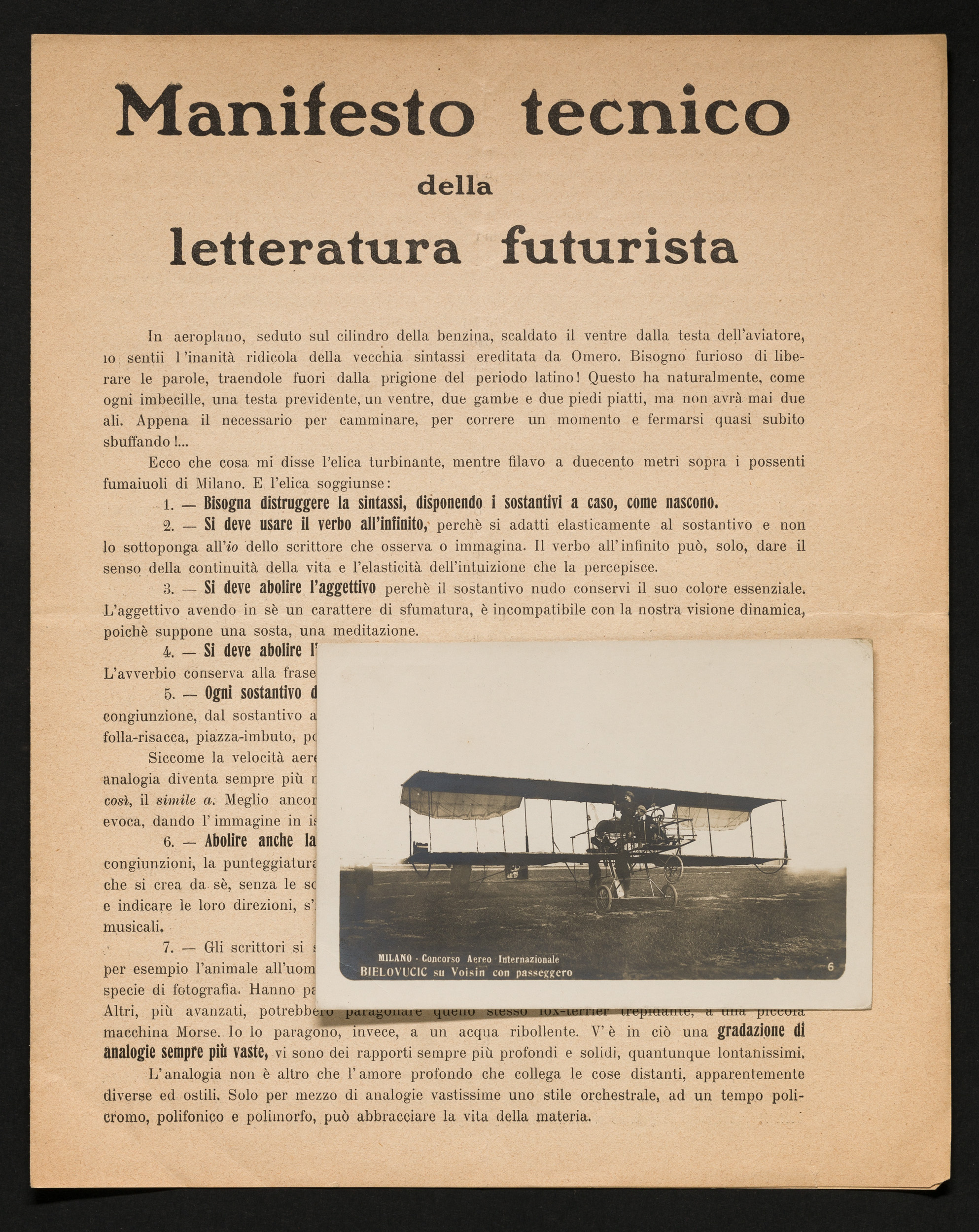

Milano. Concorso Aereo Internazionale. Bielovucic su Voisin con passaggero. September 1910.

Privatsammlung

On September 1-3, 1910, the French-Croatian-Peruvian airman Juan Bielovucic set a world record by flying from Paris to Bordeaux with stopovers for meals and lodging. At the end of the month, he and his adjusted Voisin biplane, named the Type Bordeaux after his exploit, also won several prizes at the International Air Competition in Milan, held from September 24 to October 3. It was a feature of airshows that aviators sometimes took VIP passengers to give them a taste of the air. Marinetti first flew as a passenger with Bielovucic at the Milan Competition. This postcard shows Bielovucic, his plane and a passenger, who is sitting behind and slightly above the pilot, with the propeller and the Gnome 50-horsepower motor located at the back of the fuselage.

Marinetti, Filippo Tommaso

Manifesto tecnico della letteratura futurista. Milano, 1912.

(Manifesti del Movimento Futurista, 10)

Privatsammlung

Marinetti mythologized his flight with Bielovucic almost two years later by claiming it inspired his invention of the new poetic language of parole-in-libertà. “In an airplane, sitting on the fuel tank, my belly warmed by the head of the pilot, I realized the utter folly of the antique syntax we inherited from Homer. A furious need to liberate words, dragging them free of the prison of the Latin rhetorical sentence!” So starts The Technical Manifesto of Futurist Literature, Marinetti’s first literary program, dated 11 May 1912. The manifesto calls for a poetic language even more expressive of modernity than the free verse which was the initial form of Italian Futurist poetry. The sentence was to be subjected to drastic syntactic reductionism, evoking the disjunctive structure of wireless telegraphy or the periodicity of “the spinning propeller.” Parole-in-libertà was to consist of nouns and verbs in the infinitive, but be deprived of conjugation, punctuation, prepositions, conjunctions, articles and even adjectival and adverbial modifiers. It was to look like a list. The Italian Futurists published Italian leaflets such as the one shown here for domestic consumption and French leaflets for foreign relations, mailing them, often unsolicited, to cultural figures across Europe. Kamensky read neither Italian nor French, but a hand-written translation of Italian Futurist manifestos survived among his personal papers. He therefore studied the manifestos in the fall of 1913, before Marinetti’s visit, when three collections of translated manifestos came out at once. (Indeed, the grammar of Tango with Cows is as reduced as the grammar of parole-in-libertà.) Kamensky would have been especially interested in the Italian Futurist linguistic program because of its association with aviation—unlike Marinetti, he had flown as a pilot, not just as a passenger!

Marinetti, Filippo Tommaso

Zang tumb tuuum. Adrianopoli ottobre 1912. Parole in libertà. Milano, 1914.

Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Sammlung Künstlerische Drucke

Signatur: Xr 19120<15>

Marinetti’s second manifesto of Futurist literature, “Destruction of Syntax—Wireless Imagination—Words in Freedom,” published between the spring and fall of 1913, tried to compensate for the syntactic reductionism of parole-in-libertà by calling for an expressive typography of multiple typefaces. Some of the pages of Zang Tumb Tuuum are masterpieces of iconic typographic arrangement. For example, the page on the left shows a Turkish observation balloon conveying messages by wireless telegraph (TSF): from a height of 400 meters, it has discovered that the enemy attack on the town of Süloğlu was a diversion for their true objective. The language of the wireless, invented by the Italian Marconi, provided both syntactic and imagistic models for parole-in-libertà.

Taking a closer look at Jean Cocteau’s Le Cap de Bonne Espérance (1919) and Kamensky’s Tango s korovami (1914), Dr. Anna Luhn (EXC Temporal Communities, Freie Universität Berlin) and poet Eugene OStashevsky draw connections between avant-garde poetics, dreams of aviation and acrobatic superhumanity.

Bonc-Tomaševskij, Michail Michajlovič

Kniga o tango. Iskusstvo i seksual’nost‘. Moskva, 1914.

Privatsammlung

The Book of Tango (Kniga o tango), subtitled “art and sexuality,” develops a lecture on the dance that the theater director Mikhail Bonch-Tomashevsky delivered on February 6 and 12, 1914, in St Petersburg and Moscow, respectively. The Moscow lecture was part of a colloquium on “Society and Young People,” in which Mayakovsky and Burliuk hijacked the discussion to talk about Futurism. Bonch-Tomashevsky sees the tango as an expression of “the modernity of the big city,” its discontinuous, controlled moves conveying “the rhythmic contours of the world of factories and machines.” His essay, whose arguments are more wide-ranging than deep, is illustrated by photographs of Elsa Krüger and her partner Wally demonstrating tango steps.

Elsa Krüger und Wally tanzen Tango.

Postkarten von D. Chromov and M. Bachrach. Moskva, 1914.

Privatsammlung

These are two of about two dozen postcards in which Elsa Krüger and Wally, dancers at Maria Artsybusheva’s Theater of One-Act Plays, Moscow, demonstrate the moves of tango and maxixe. The postcards are probably promotion material for an instructional reel, starring Krüger and Wally, that ran in Moscow movie theaters around the New Year of 1914 but has not survived. Elsa Krüger, Moscow’s “Queen of Tango,” is said to have associated with the Larionov-Goncharova gang. The group’s promotional tactics in the fall of 1913 included going into night clubs in the company of society women dancing the tango, whose arms and chests they painted with Futurist designs. However, Krüger did not star in Drama in Futurist Cabaret Number 13, a parodic two-reel by the group which was shown in movie theaters in January 1914 but also has not survived. In 1920 Krüger moved to Berlin, where she danced with the , starred in films (Die Villa im Tiergarten, 1927, and Grenzfeuer, 1934) and even had a brand of cigarettes named after her. Each pack of Elsa Krüger cigarettes contained a different photo of Elsa like a tiny heart.

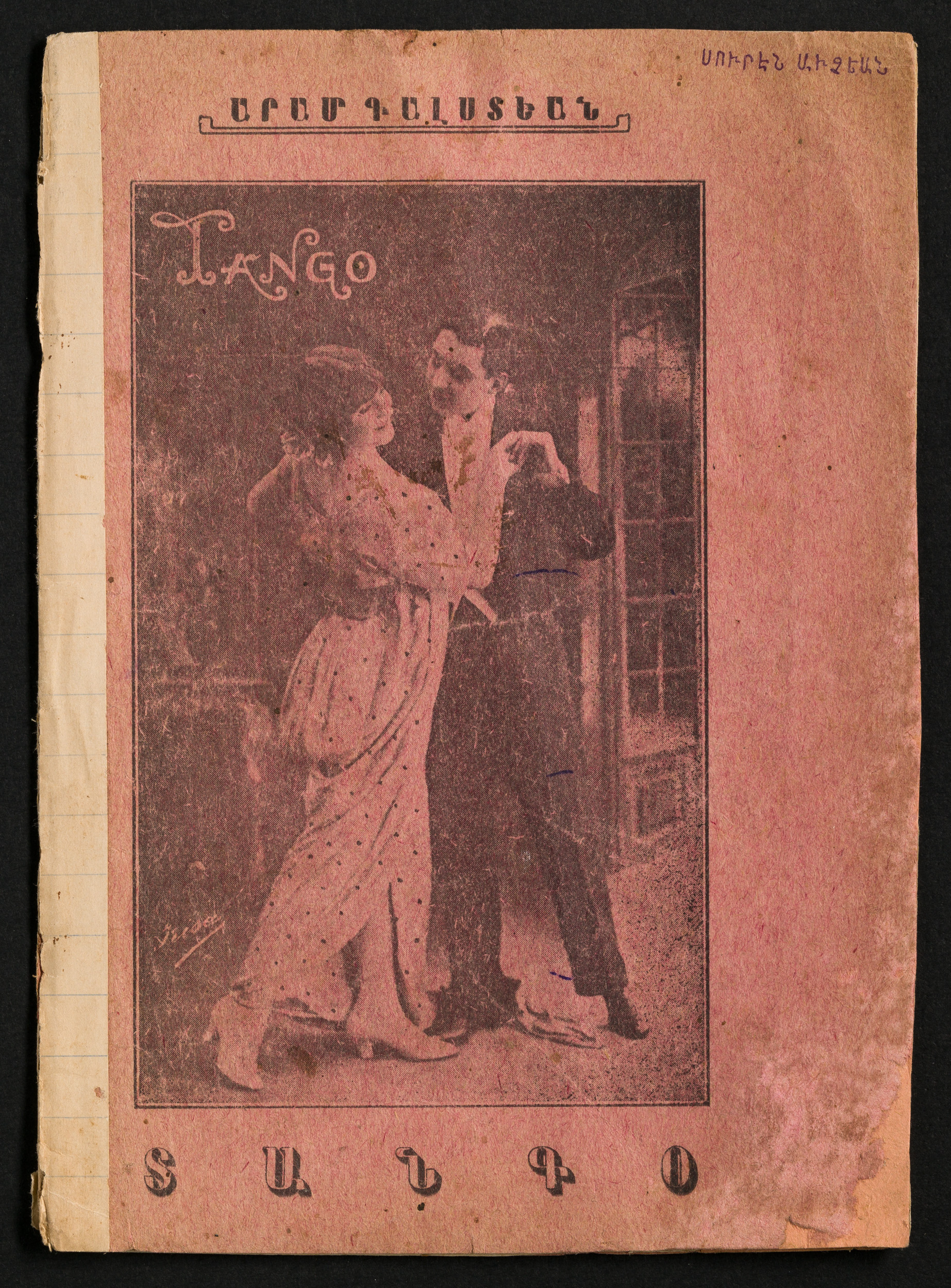

Galstean, Aram

Tango. Tiflis, ca. 1914.

Privatsammlung

The tango craze of 1913-14 was a global phenomenon with its epicenter in Paris rather than Buenos Aires, where the dance had been born. “Tangomania” was not just about dancing, but also about shopping. Tango-themed merchandise, clothes as well as other luxury items flooded the market in places as far apart as Oakland, California, and Tiflis (Tbilisi), Georgia. This chapbook called Tango, presumably from 1914 or thereabouts, was self-published by Aram Galstyan (also Galustov), an Armenian amateur poet residing in Tiflis. It laments the effect of tangomania on family budgets and relations. “Husbands suffer greatly / On account of their wives / Buying goods called “tango” / Emptying out their pockets // Husbands go mad / Drown themselves from grief / Their daughters and wives / Demand tango dresses // Married couples break up / They live separately / They don’t talk to one another / Because of tango pumps // … Dresses, hats and shoes, / Hat pins and flower vases, / Cutlery, trays, and glasses / Anything you want comes in the style of tango!”

Terentʹev, Igorʹ Gerasimovič

Traktat o splošnom nepriličii. Tiflis, 1919.

Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Rara-Sammlung

Signatur: 3 A 170565

Igor Terentiev’s Tractatus on Sheer Obscenity (Traktat o sploshnom neprilichii) was released in the capital of then-independent Georgia in 1920. It came out under the label of 41°, the extreme Futurist group composed of Alexei Kruchenykh, Ilya Zdanevich and Terentiev himself. The 41° group favored zaum (abstract sound poetry) and developed avant-garde typography in response to the multilingual environment of Tiflis, and to Georgian and Armenian languages and alphabets in particular. Many of their positions evoke the contemporaneous Dada movement. Terentiev was the group’s irrepressible offender. The projectile vomit that is the Tractatus rejects intellectualism in favor of the “entirely meaningless, useless, angry, plain, uncomfortable, simple, and whining NAKED FACT!” Challenging his reader to embrace their inner stupid, the author fills his text with sexual and scatological puns, a 41° practice which they arrived at by reading Freud (so much for anti-intellectualism). It is possible that Zdanevich realized the brochure’s stunning typography.

Parnach, Valentin Jakovlevič

Motdinamo. 8 ill. d’après les dessins de N. Gontcharova. La couverture et 7 ill. d’après les dessins de Larionow. Paris, 1920.

Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Rara-Sammlung

Signatur: 4” 19 ZZ 10248

Motdinamo or Slovodvig (Wordmove) is the second book of poems by Valentin Parnakh published by the artists Mikhail Larionov and Natalia Goncharova in Paris. Larionov and Goncharova, who regularly collaborated with poets on lithographed chapbooks, met the poet after they moved to the French capital. The multitalented Parnakh was performing as an “eccentric dancer” at French Dada events while writing poetry with the more avant-garde Russian émigrés. His Motdinamo presents the handwritten text in Russian and then in French self-translation. The book tried to compose poetry about dance that would itself be like dance. Its syncopated rhythms are full of dance terms, some of which may be presumed semantically opaque for its readers; they are therefore read gesturally, as if they were dance moves or sound poems. Imagine, for example, the French reader confronted by the following “translation,” which is really an exercise in translingualism: “Khabarda! / Dans le désespoir des Revolutions massacrez / Le corps des notes, la Doubinouchka, le Czardas! / Voici qu’à Petrograd, à Budapest / L’orchestre fait explosion! Un orde / De Fox-trot domine le monde, / Clameur du côté de Caucase ¡Khabarda!” and so on. (“Dubinushka” is a Russian song, “Czardas” is a Hungarian dance, “Khabarda,” derived from Persian, means “watch out”; also note the punctuation, originating in Parnakh’s study of Spanish.) Among his many other achievements, Parnakh was the first Russian jazzman. He returned to Moscow in 1922 with exotic musical instruments in his baggage, founding “The Eccentric Orchestra Jazz Band of Valentin Parnakh,” the first Russian jazz ensemble. In Moscow Parnakh was roommates with Osip Mandelstam, who makes ungentle fun of him in The Egyptian Stamp, even laughing at the expensive vergé paper that Motdinamo is printed on. Returning from France again in the 1930s, Parnakh published an anthology of translations of Jewish poets persecuted by the Inquisition, and, in the 1940s, an abbreviated version of Agrippa d’Aubigné’s epic of the persecution of French Protestants during the Wars of Religion, Les Tragiques. How somebody like that managed not to get killed during the Stalin years is beyond comprehension.

Dr. Alexandra Ksenovontova (EXC Temporal Communities, Freie Universität Berlin) and poet Eugene Ostashevsky discuss the interrelations of dance, words in movement, and avant-garde translation in Valentin Parnach’s Motdinamo (1920) and Kamensky’s Tango with Cows (1914).

„Танго с коровами – Tango s koróvami – Tango with Cows“

Kamenskij, Vasilij; Ostashevsky, Eugene; Mellis, Daniel

Tango with cows. Translation, Facsimile and Commentary. Chicago, 2022.

Geschenk an die Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz

Kamenskij, Vasilij

Tango s korovami. Faksimile. Moskva, 1991.

ISBN 5-212-00585-X

Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz

Signatur: 50 MA 17066

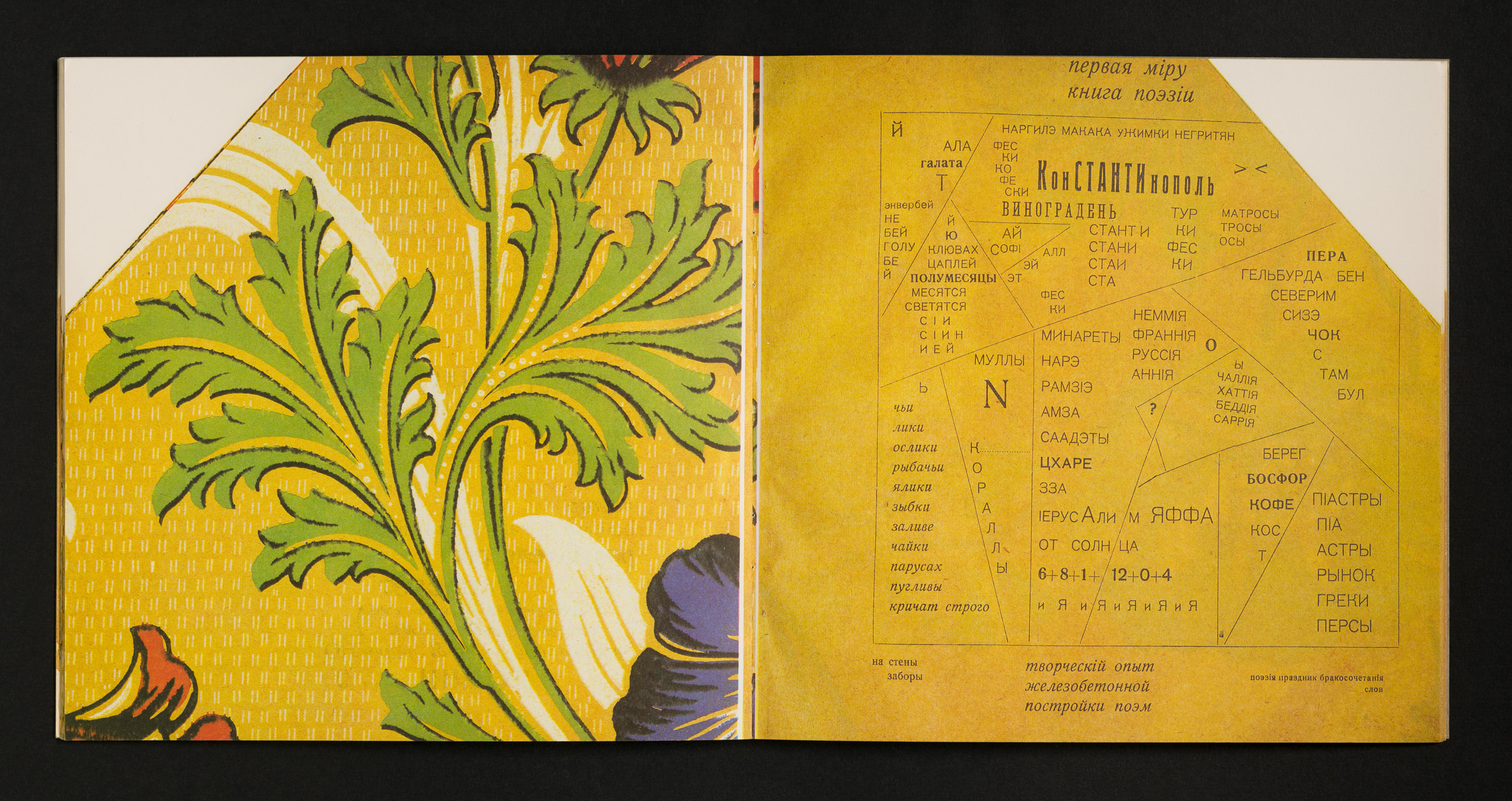

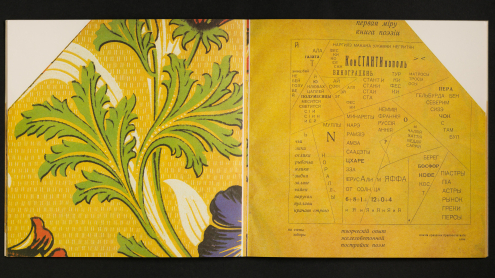

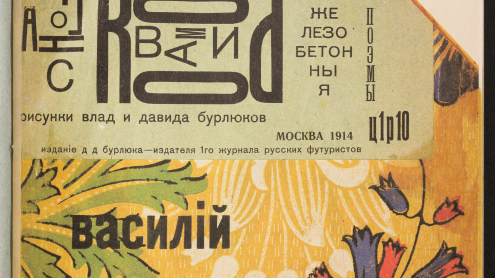

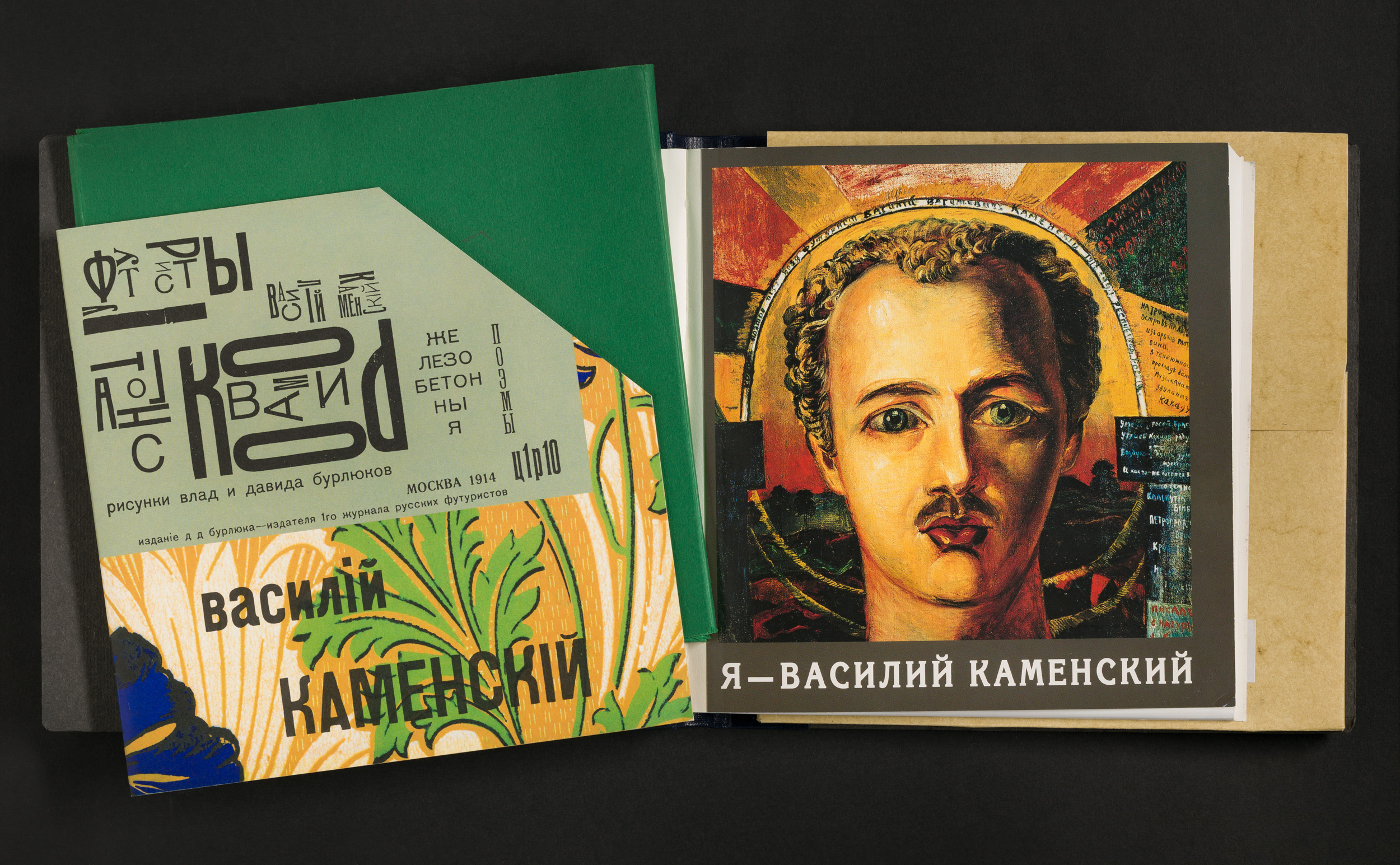

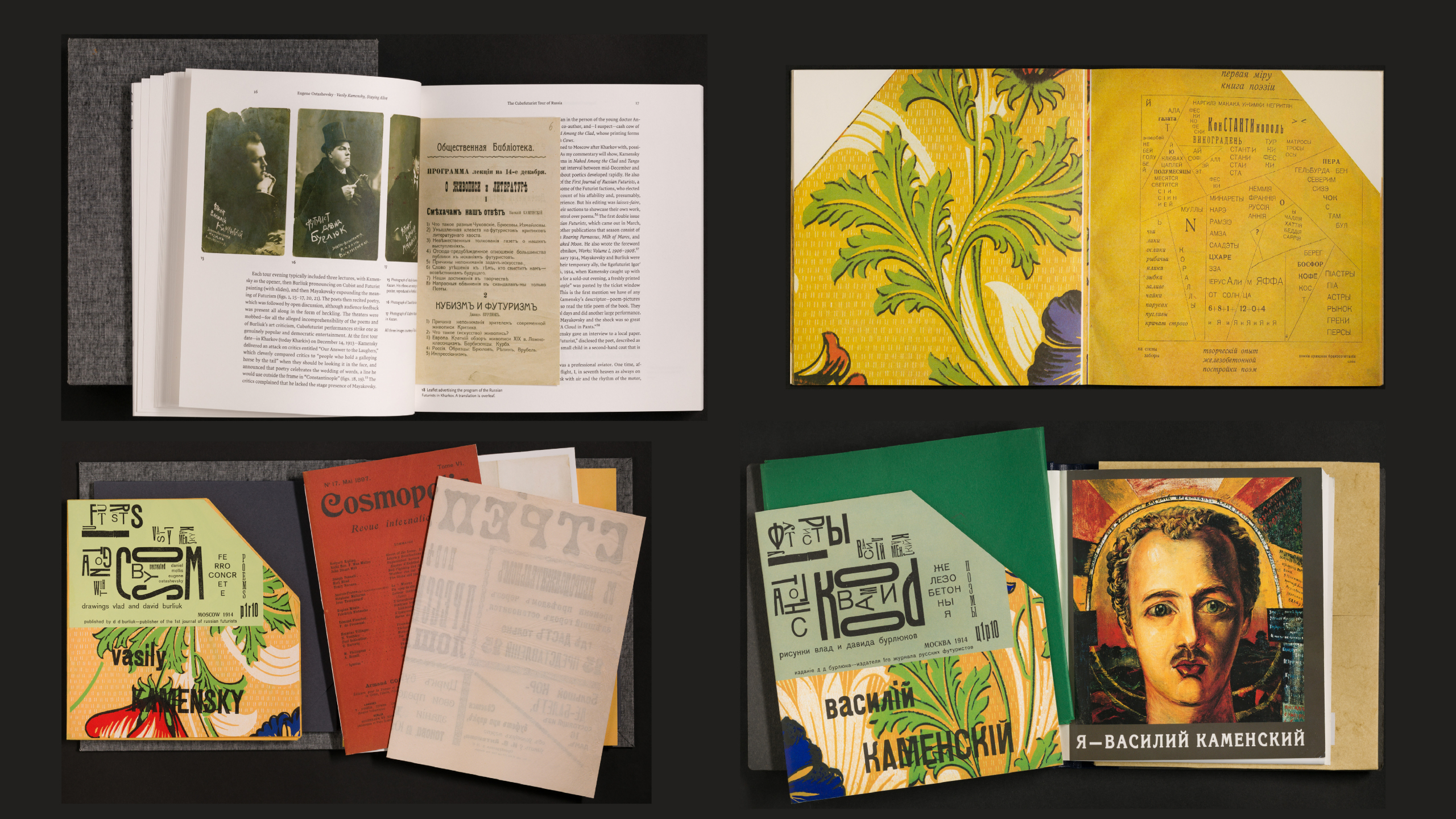

This is a facsimile edition of Kamensky’s Tango with Cows (Tango s korovami), published in Moscow in 1991. The original came out in March 1914 in an edition of 300 copies printed on the back of brash, “tango”-colored cheap wallpaper. Only a few dozen remain in museums and libraries. The Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin does not own a copy, but the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek does. The book’s cornucopia of typefaces recalls the eye-catching typography of posters for Cubofuturist readings, where different typefaces formed a single word. Kamensky invented the term “ferroconcrete poems” to describe the typographic visual poems in this book (and in its predecessor, the even rarer Naked among the Clad (Golyi sredi odetykh), published in February). The especially experimental “ferroconcrete poems” were those which, framed and broken up into compartments, look like Cubist paintings made of words. Like pictures, they have no clear reading order, nor do they carry over to the next page. They consist mostly of nouns, recalling the parole-in-libertà of Italian Futurism, but the words are connected to one another by sounds and puns, which is a Russian Futurist technique. Other Russian Futurist techniques in Tango with Cows are the tendency to look at words as letter sequences which may be disassembled, shortened or reordered at will, and also the employment of such sequences without definite meaning (zaum). Kamensky’s ferroconcrete poem “Constantinople” supposedly relates his impressions of the city when he visited around 1905 but it also incorporates recent newspaper accounts. Many of his impressions of the city have to do with sounds, and one zaum-like sequence turns out to be a Turkish phrase. The more conventional words are broken up and punningly fitted inside other words, such as in the description of the activities on the city’s quays: “matrosy / trosy / osy” (literally, sailors / cables / wasps). Some of the techniques anticipate the concrete poetry of the 1950s and 60s. The words around the frame attest to the poem’s previous life as a poster: it hung outside a Cubofuturist reading in Odesa in January 1914.

Kamenskij, Vasilij

Tango s korovami. Faksimile. Moskva, 1991.

ISBN 5-212-00585-X

Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz

Signatur: 50 MA 17066

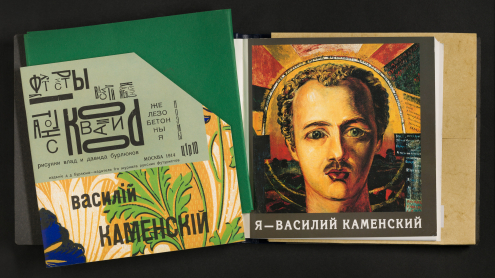

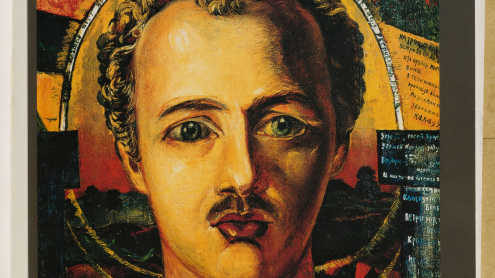

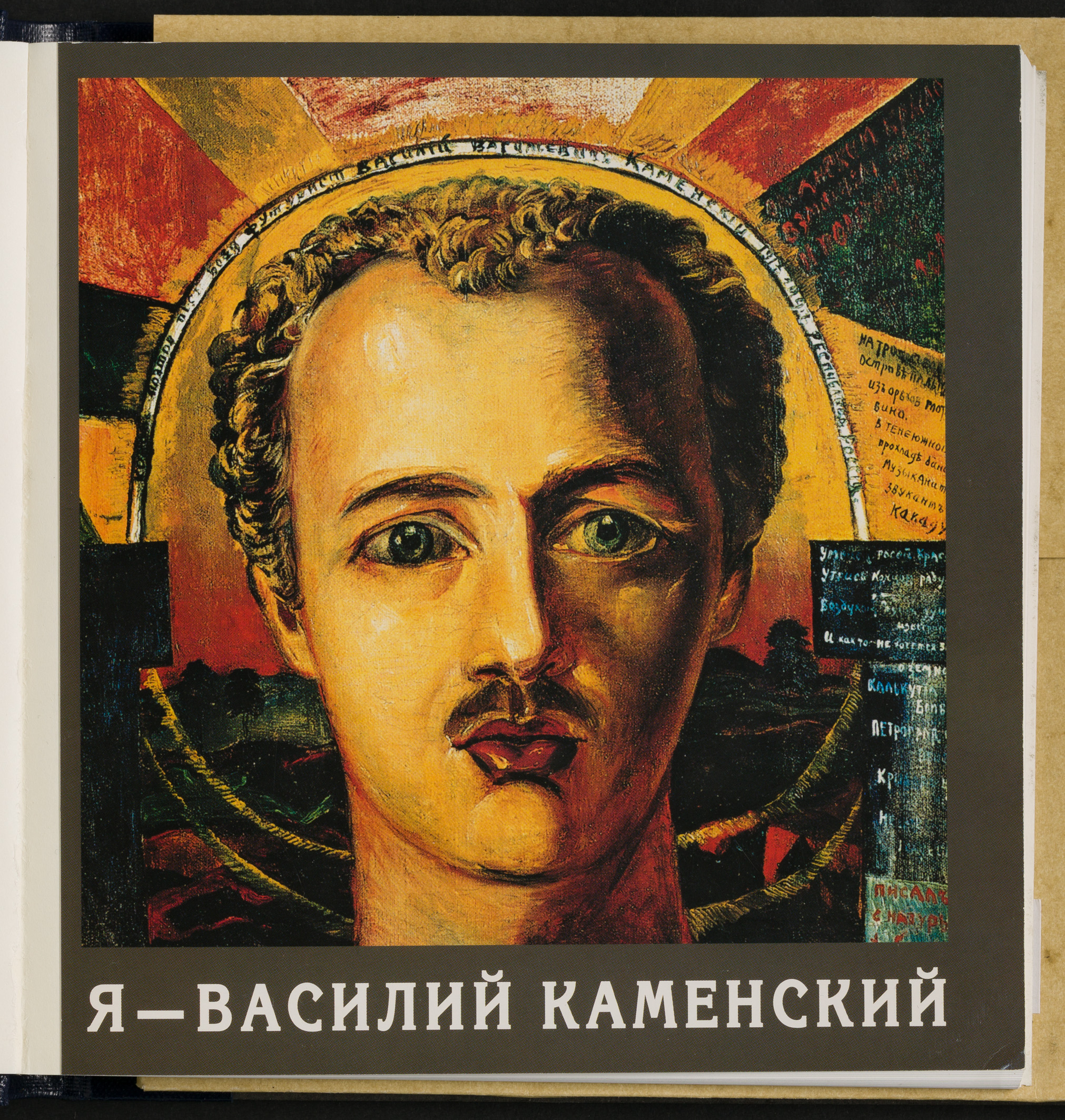

Ja – Vasilij Kamenskij. Sbornik. Sostavitel’ A. Aksenkin. Moskva, 2006.

Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz

Signatur: 3 A 140330

This volume of Kamensky memorabilia was released in 2006 by the Mayakovsky Museum in Moscow. It contains this photo of Kamensky in an Etrich Taube monoplane at the Aviata flying school on the Mokotów Field in Warsaw. The picture was taken in November 1911, when the poet passed his aviator license exam, the 67th person to receive a license from the Imperial All-Russian Aeroclub. Although Kamensky owned and subsequently flew a Blériot XI, he trained at Aviata to take his exam with a Taube. His teacher, the ace Khariton Slavorossov, would survive a dramatic crash in a show flight during the solar eclipse of April 17, 1912. Kamensky himself would survive a less dramatic crash three weeks later, during a show flight at Częstochowa. It was to be his last. Reports of these incidents, especially Slavorossov’s, possibly inspired the ending of Kruchenykh’s opera, Victory over the Sun.

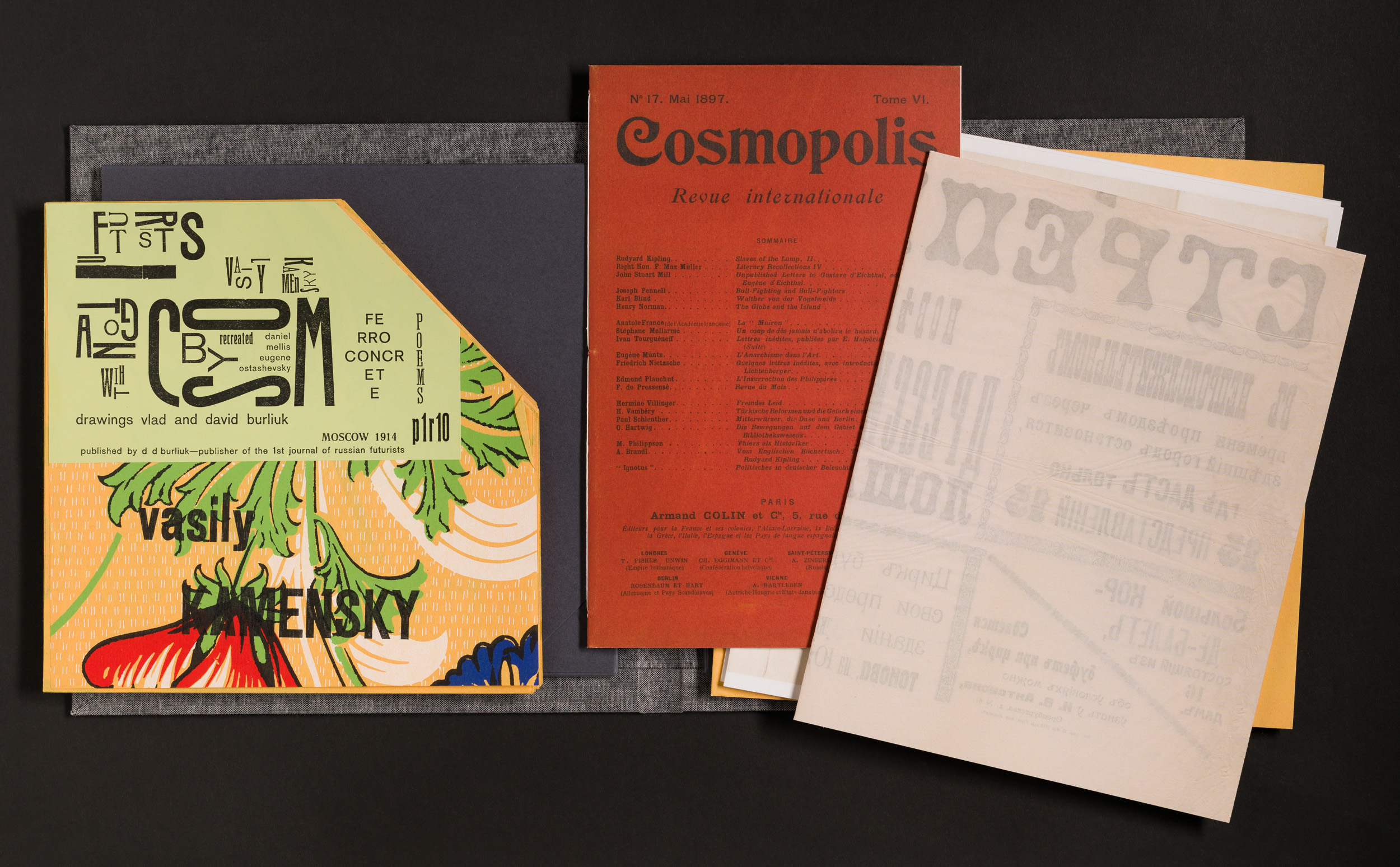

Kamenskij, Vasilij; Ostashevsky, Eugene; Mellis, Daniel

Tango with cows. Translation, Facsimile and Commentary. Chicago, 2022.

Geschenk an die Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz

Tango with Cows: Translation, Facsimile and Commentary by Daniel Mellis and Eugene Ostashevsky is a fine-press edition of Kamensky’s book that consists of a “visual translation” of the Russian original into English, a commentary volume of over 300 illustrations and a portfolio of facsimiles of related publications and ephemera. The translation aims to resemble the original not only in meaning but also in appearance. It is printed in letterpress, using the Latin counterparts to the Cyrillic typefaces employed by Kamensky’s printer Yakovlev on custom-made wallpaper that reproduces the wallpaper of the 1914 edition. The accompanying scholarly volume includes a biography of Kamensky up to 1914 and an in-depth study of the book-art aspects of Tango with Cows together with an analysis of its typefaces. The commentary chapter walks the English-language reader through the Russian original word by word, offering a “thick translation” that augments the poetic translation in the chapbook. The commentary also describes the forms and venues of popular entertainment in Moscow during the tango craze of 1913-14, indicating the nightclubs, films, the circus, roller-skating, baths and galleries that serve as the subjects of individual poems. For example, the action in “Cabaret Zon” takes place in two fashionable Moscow nightspots: the Zon café and theater, and the Maxim restaurant. Most of the poem explores the goings-on on the two floors of Zon—the onstage acts, champagne, snacks, prostitutes and tango. The words float like couples dancing to the rhythms of the music. The invisible observer’s perceptions and thoughts appear side-by-side in an example of Futurist simultaneity. After hours of dancing, he stumbles into the late-night Turkish Café in the basement of Maxim, where, too drunk to move, he is subjected to the music of Inayat Khan’s Indian Orchestra. By the way, Maxim was owned and run by the African-American entrepreneur Frederick Bruce Thomas, who also owned the roller-skating rink described in another poem in the same book. As for the Indian Orchestra, its head, the Indian Muslim poet and musician Hazrat Inayat Khan, soon returned to London, where he established a Sufi order that exists to the present day.

Diese virtuelle Präsentation begleitet die Veranstaltung

Konzept und Kuratierung: Eugene Ostashevsky mit Susanne Frank (EXC Temporal Communities / Humboldt-Universität Berlin), Olaf Hamann (Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin), Anna Luhn (EXC Temporal Communities)

Gestaltungskonzept und Umsetzung: Mara Eling (Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin), Anna Luhn, Franka Schmuck (EXC Temporal Communities)

Beratung und Provenienzforschung: Olaf Hamann, Sabine Kaiser (Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin)

Fotos: Fotostelle der Staatsbibliothek