Library Stories

Library Stories

Work and Life in the Stabi 100 Years ago

The exhibition “Library Stories. Work and Life in the Stabi 100 Years ago” was created as part of a project seminar.

In the summer semester of 2025, a group of students from the Cultural Studies (BA) and Comparative Literature and Art Studies (MA) programs at the University of Potsdam met once a week in the Oxford Room of the Staatsbibliothek to explore the history of Berlin and the library around 1900.

The central source for the seminar consisted of historical personal files of former library employees of the Stabi — a collection of biographies, employment records, letters, medical certificates, and vacation requests. During the seminar, the students learned to read and transcribe historical handwriting and, in this way, researched the curricula of five exemplary employees — their social background, education, interests, and opportunities within the library a hundred years ago.

This exhibition is the result of these investigations. It was displayed in Café Felix from October 10, 2025 to January 30, 2026 and is still visible here online.

Posters

Biographies and Excerpts from Personal Files

Friedrich Selle

Soldier, House Servant, Library Servant

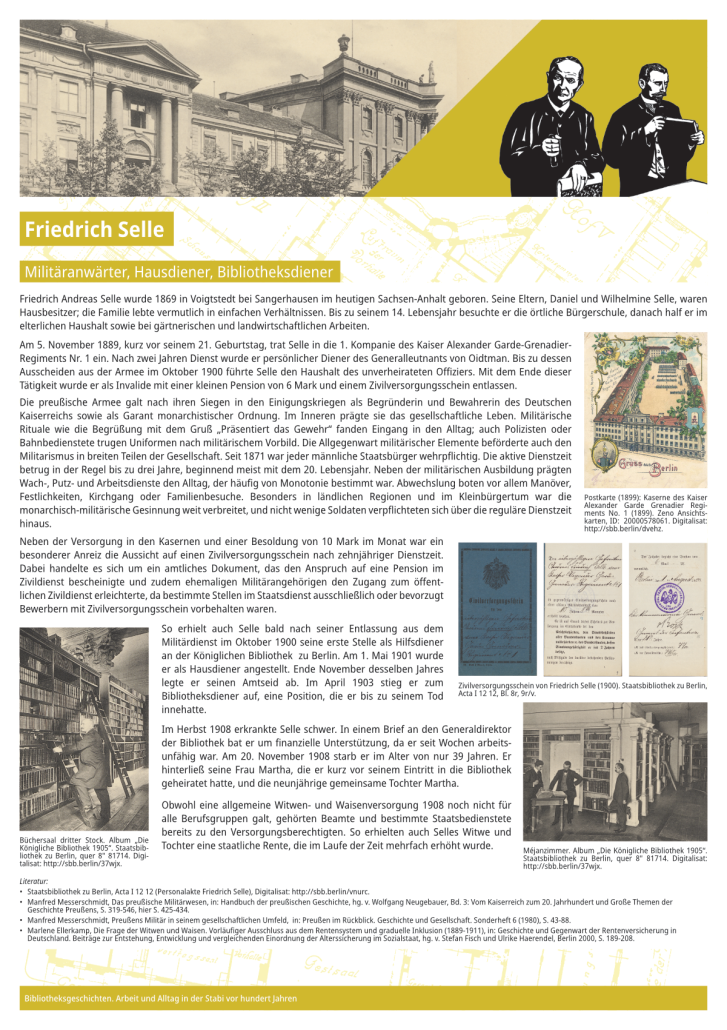

Friedrich Andreas Selle was born in 1869 in Voigtstedt near Sangerhausen, in present-day Saxony-Anhalt. His parents, Daniel and Wilhelmine Selle, were homeowners, and the family likely lived in modest circumstances. Until the age of fourteen, he attended the local elementary school, after which he helped with household, gardening, and agricultural work.

On November 5, 1889, shortly before his 21st birthday, Selle joined the 1st Company of the Kaiser Alexander Garde Grenadier Regiment No. 1. After two years of service, he became the personal servant of Lieutenant General von Oidtman. Until the officer retired in October 1900, Selle managed the household of the unmarried officer. Upon leaving this position, he was discharged as a disabled veteran, receiving a small pension of 6 Marks and a civil service certificate.

The Prussian army, celebrated for its victories in the Wars of German Unification, was regarded as the founder and guardian of the German Empire and a guarantor of monarchist order. It also shaped social life at home. Military rituals, such as the greeting “Present arms,” became part of daily life, and even police officers or railway employees wore uniforms modeled on military dress. The omnipresence of military elements reinforced militarism across broad sections of society. Since 1871, every male citizen was subject to conscription, typically serving up to three years beginning around the age of 20. Daily life was structured by guard duties, cleaning, and other work, often monotonous, with occasional relief through maneuvers, festivities, church attendance, or family visits. In rural areas and among the lower middle class, monarchist-military attitudes were widespread, and many soldiers voluntarily extended their service beyond the mandatory term.

In addition to accommodation in barracks and a monthly salary of 10 Marks, a particular incentive was the prospect of obtaining a civil service pension certificate (Zivilversorgungsschein) after ten years of service. This official document confirmed entitlement to a pension in civil service and facilitated access to public service positions, as certain state jobs were reserved exclusively or preferentially for applicants with such a certificate.

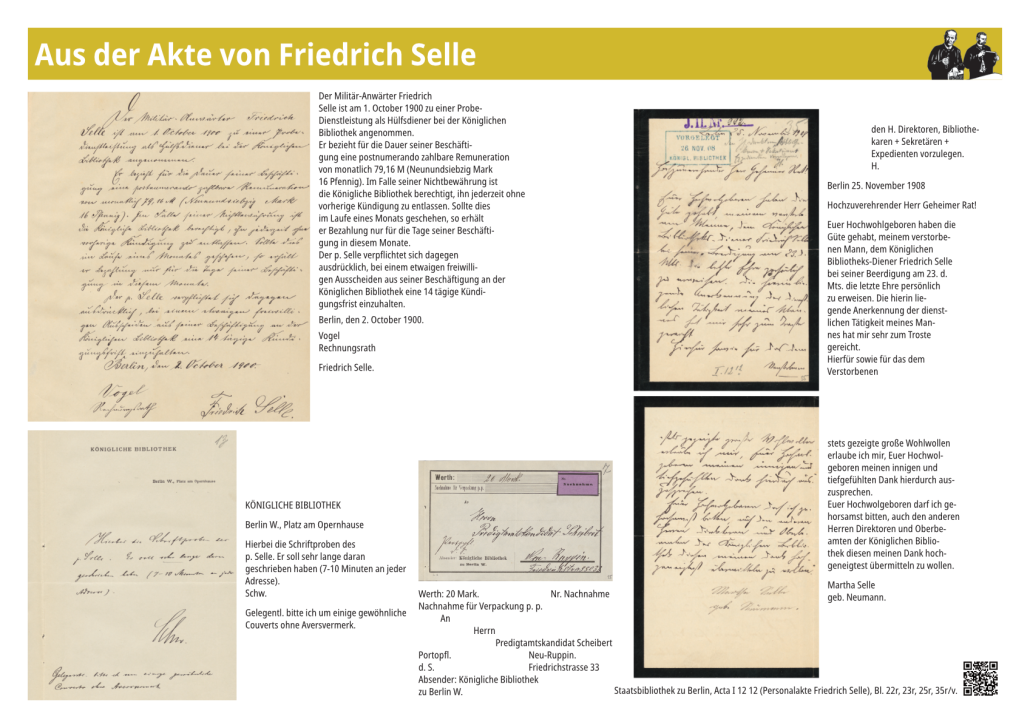

Shortly after his discharge from military service in October 1900, Selle received his first position as an auxiliary servant at the Royal Library in Berlin. On May 1, 1901, he was employed as a house servant and took his official oath at the end of November that same year. In April 1903, he was promoted to library servant, a position he held until his death.

In the autumn of 1908, Selle fell seriously ill. In a letter to the Director General of the Library, he requested financial support, as he had been unable to work for weeks. On November 20, 1908, he died at the age of only 39. He left behind his wife Martha, whom he had married shortly before joining the library, and their nine-year-old daughter, also named Martha.

Although a general widow and orphan pension system was not yet available for all professions in 1908, civil servants and certain state employees were already entitled to such benefits. Selle’s widow and daughter therefore received a state pension, which was subsequently increased several times.

Illustrations:

Postcard (1899): Barracks of the Kaiser Alexander Guard Grenadier Regiment

Civil Service Pension Certificate of Friedrich Selle (1900)

Book Hall, Third Floor

Méjan room

The German source text was translated with the assistance of ChatGPT and then revised for accuracy and style.

Emmy Tillmanns

Teacher, Auxiliary Worker, Library Secretary

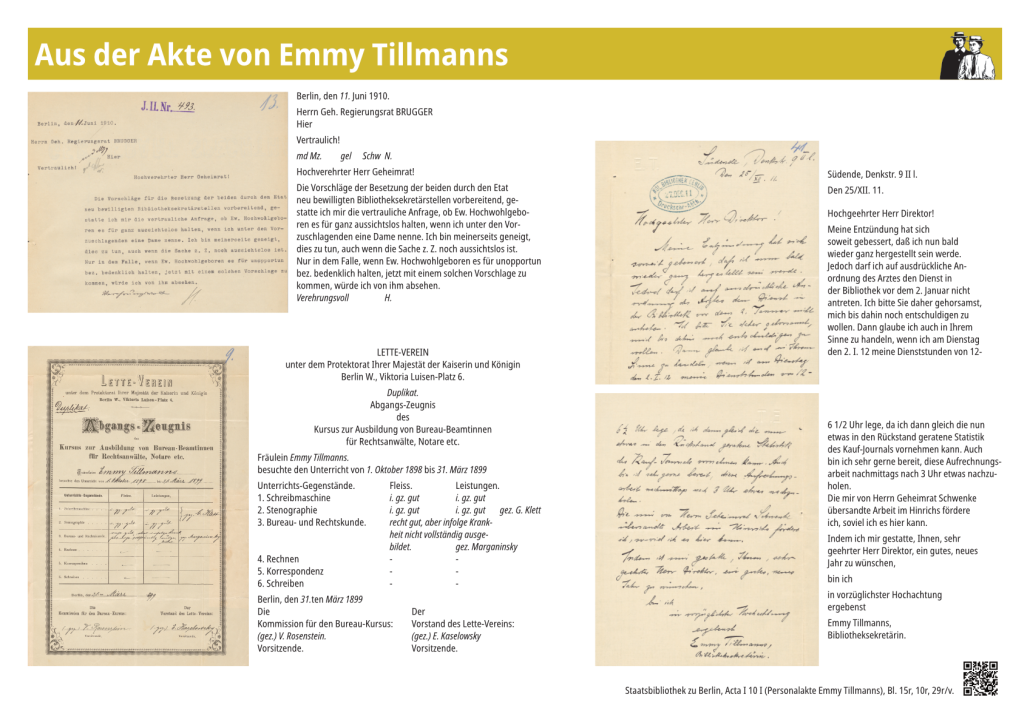

Emilia (Emmy) Wilhelmine Victoria Tillmanns was born on January 26, 1871, in Cleve. She completed her schooling at the age of 15 and then prepared for admission to a teachers’ seminar, which she attended from 1890 in Frankfurt am Main. After three years, she graduated, qualifying as a teacher for higher and middle girls’ schools as well as a handicrafts teacher. From 1893 to 1896, Tillmanns worked as a municipal teacher in Elberfeld. Due to a throat condition, she had to leave the teaching profession and subsequently provided private lessons – first in Elberfeld, later in Berlin. In 1898/99, she completed a course at the Berlin Lette-Haus in office administration, shorthand, and typewriting. The Lette Association, founded in 1866 to promote the employability of women, played a key role in advancing women’s economic independence by preparing them for professional work.

Between 1899 and 1905, Tillmanns worked as an auxiliary employee at the Society for German Educational and School History in Berlin. Her varied tasks included bibliographic work, translations from English and French, and proofreading. Her diligence, punctuality, and thoroughness were emphasized in a reference, and she was explicitly recommended for work as a librarian or private secretary. However, after an internal restructuring of the society, her position was eliminated.

In 1905, she found employment at the publishing house Hachmeister & Thal in Leipzig, where she worked as a proofreader and expedient. She handled corrections in German, French, and English, maintained manuscript books, and took on organizational tasks. Again, she was described in a reference as extremely reliable and qualified. She left the publishing house in 1906 at her own request.

On May 1, 1906, Tillmanns joined the Royal Library in Berlin as an auxiliary worker. Despite health difficulties – by 1909 she required extended hospital treatment due to chronic joint inflammation – she continued her work at the library. In 1911, she was one of the first women to be appointed as a library secretary and granted civil service status. Tillmanns worked in the Printed Works Department, specifically in the acquisitions section, recording gift acquisitions and purchases.

In the following years, her health deteriorated further. She suffered from joint inflammation and stiffness, necessitating multiple long-term leaves and stays at health resorts. In September 1913, her doctors advised her to retire, as pensioning would inevitably be required. Although she attempted to continue working, she ultimately submitted a resignation in 1916 and moved into the “Ladies’ Home of the Protestant Women’s Association for Educated, Sick Women.” On July 1, 1916, she was officially retired. As a civil servant, she received a state pension, but it was insufficient to cover the care she needed, leaving her dependent on additional financial support.

Emmy Tillmanns died on May 8, 1921, at the age of only 50 from the effects of pneumonia.

Illustrations:

Female Library Staff

Staff of the Printed Works Department

Staff of the Purchased and Legal Deposit Acquisitions (ca. 1931)

Obituary of Emmy Tillmanns

The German source text was translated with the assistance of ChatGPT and then revised for accuracy and style.

Charlotte Schmidt

Teacher, Auxiliary Worker, Library Secretary

Charlotte Schmidt was born on April 7, 1885, in Berlin. From the age of twelve, she attended the higher girls’ school run by Miss Gabriele Plehn in Berlin. In 1901, she transferred to the teachers’ training institute of the same school and successfully passed the teaching examination there in 1904.

Afterwards, Schmidt pursued further education, particularly through language courses in French and English. At the same time, she gave private lessons to students at Dr. Knauer’s Higher Girls’ School. She continued to advance her education by attending lectures at the Viktoria Lyceum in Berlin and courses by Professors Peabody and Sefton Delmer at Berlin University. She also acquired practical skills, completing training in typewriting – with a performance of 85 lines per hour – and learning shorthand in 1909/10.

Charlotte Schmidt began her professional career in 1906 as an auxiliary worker at the office of the Union Catalogue of Prussian Libraries. After completing the cataloguing work there, she had to leave the position in 1908. Her reference praised her punctuality, diligence, and conscientiousness.

On April 1, 1908, she moved to the Royal Library in Berlin as an auxiliary worker. There, she was initially responsible for the card catalogue and gained insights into the workflows of other departments. In 1910, she passed the diploma examination for the intermediate library service – for both academic and public libraries – with the grade “good.”

In 1911, she was officially appointed as a library secretary at the Royal Library, working in the Printed Works Department. Her tasks initially included cataloguing for the alphabetical card catalogue, and from 1913 she worked on title prints.

On May 14, 1918, Schmidt married a soldier in a so-called war-time wedding. Upon her marriage, she had to give up her civil service position, but with the explicit consent of the Director General, she was allowed to continue working as an auxiliary worker in the library until the end of the war.

Illustrations:

Diploma Examination Certificate

Postcards (1913)

Female staff of the Royal Library in the hospital library (Autumn 1915). The person in the first row on the far right may possibly be Charlotte Schmidt (see handwritten names added later).

The German source text was translated with the assistance of ChatGPT and then revised for accuracy and style.

Carl Georg Brandis

Classical Philologist, Librarian, Director

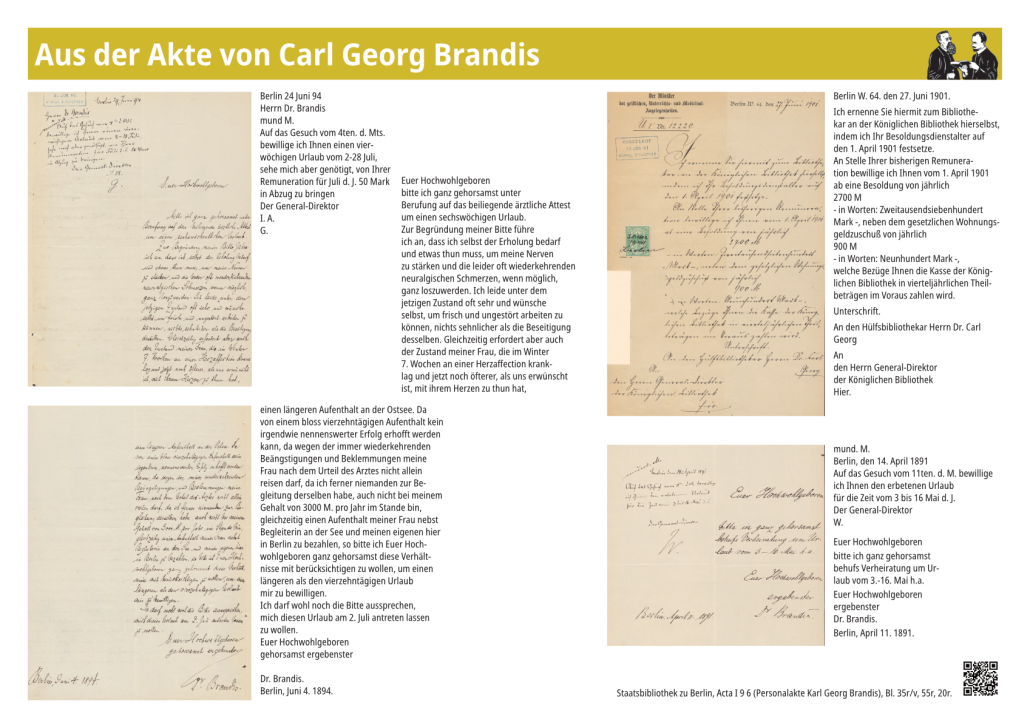

Carl Georg Brandis was born on April 10, 1855, in Copenhagen, as son of the German clergyman Christian Brandis. After the family moved to Schleswig-Holstein, he first received private lessons and then attended the Christianeum Gymnasium in Altona. He went on to study Classical Philology in Leipzig and Bonn. In 1881, he earned his doctorate with a dissertation on phonetics in Latin and obtained his teaching qualification for Latin and Greek.

Brandis began his professional career as a private tutor and educator. In Bonn, he taught the sons of Privy Councillor Roderich von Stintzing and accompanied two students to the University of Strasbourg. In 1883, he entered the service of the court of the Duke of Sachsen-Weimar-Eisenach, where he educated the princes Wilhelm Ernst and Bernhard Heinrich. The Duke placed particular importance on providing his sons with a comprehensive scientific and artistic-literary education in the spirit of Weimar Classicism. When the princes began attending a secondary school in Kassel in 1890, Brandis’s duties at court came to an end.

That same year, he began his service at the Royal Library in Berlin. Initially employed as an auxiliary worker, he advanced quickly – becoming an assistant in 1894, an assistant librarian in 1897, and finally a librarian in 1901. During this time, he was involved in cataloguing and developing the library’s collections, while also publishing numerous scholarly works on philological, historical, and archaeological topics. His articles appeared, among others, in the journal Hermes and in the new edition of Paulys Realencyclopädie der classischen Altertumswissenschaft – the most comprehensive reference work on classical antiquity – edited by Georg Wissowa from 1890 onward. His wife Frieda, whom he married in 1891, actively supported him in his work.

In 1903, Brandis moved to Jena, where he became director of the University Library. The position had originally been intended for another candidate, but after that person declined, Brandis was chosen. By accepting the post, he stepped into a role with a distinguished tradition – Johann Wolfgang von Goethe himself had directed the Jena Library from 1817 to 1824 and had significantly expanded its collection. Brandis also implemented reforms: he consolidated various catalogues, improved administrative procedures, expanded the collections, and established an extensive periodicals collection.

Alongside his duties as library director, he remained active in scholarship, continuing to publish – including studies on the history of the Jena University Library and on Goethe. In 1925, he officially retired but continued to manage the library for nearly another year until his successor took over. He then volunteered as head of the reading room.

Carl Georg Brandis passed away in Jena on July 28, 1931, only eight days after his wife Frieda. A former colleague described him as a kind and collegial superior who enjoyed the trust of everyone around him.

Illustrations:

Portrait of Carl Georg Brandis

Brandis (No. 3) at a celebration with other librarians of the Royal Library (after 1891).

The German source text was translated with the assistance of ChatGPT and then revised for accuracy and style.

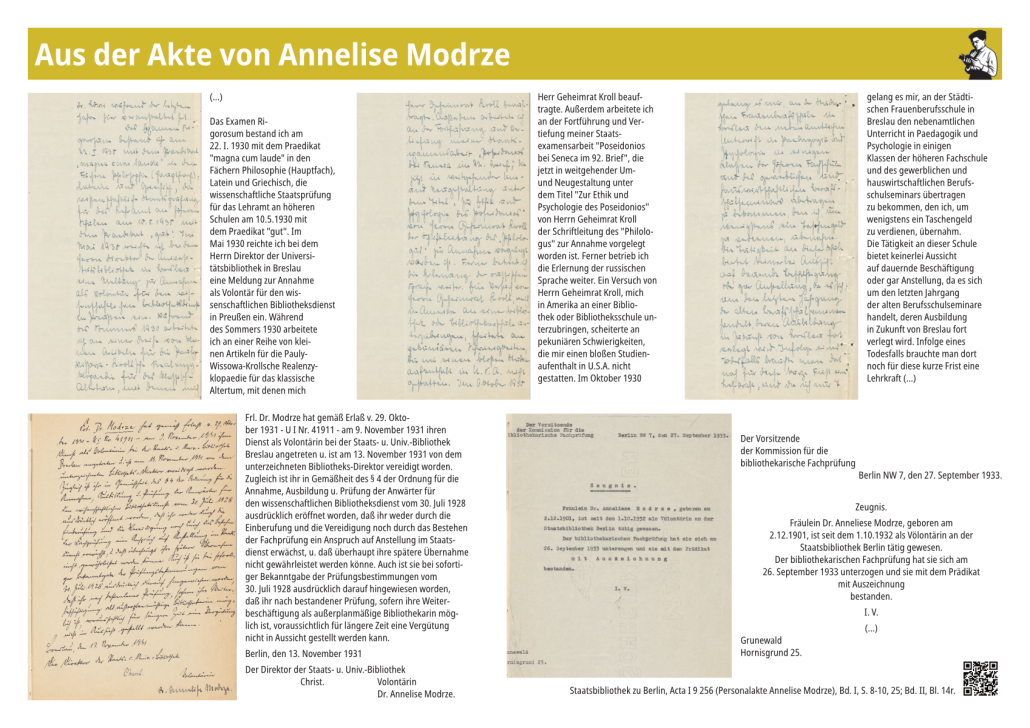

Annelise Modrze

Classical Philologist, Trainee, Academic Librarian

Annelise Modrze was born in 1901 in Kattowitz, Upper Silesia. Her father was a civil servant with the Imperial Railways in the Prussian state service, and her mother came from a Jewish family but had been baptized as a protestant. The family environment was shaped by middle-class educational values and a strong sense of duty.

After attending the Lyceum (a girls’ secondary school) in Hanover, she completed her Abitur in 1921. Although it had been possible for girls to obtain this qualification since the late 19th century, even in the 1920s only a small fraction of female students had access to higher education. Because Ancient Greek was not part of the curriculum at girls’ schools, Modrze had to learn it later at university in order to be admitted to study classical philology – an example of the structural barriers women had to overcome on their way to university.

Modrze studied philosophy, German, and history at the universities of Heidelberg and Wrocław before switching to classical philology and archaeology. In 1930, she earned her doctorate in classical philology at the University of Wrocław. Her dissertation, “On the Problem of Script: A Contribution to the Theory of Decipherment,” combined philological questions with linguistic and semiotic considerations – an approach that her examiners praised as methodologically clear and innovative.

After completing her doctorate, Modrze obtained a position as a trainee (Volontärin) at the University Library of Wrocław. Both before joining the library and during her traineeship, she authored numerous scholarly articles, including contributions to Paulys Realencyclopädie der Altertumswissenschaft. After a year in Wrocław, she continued her traineeship in 1932/33 at the Prussian State Library in Berlin. There, she worked in the Manuscript Department, cataloguing medieval manuscripts, and was regarded by both supervisors and colleagues as exceptionally diligent, well-read, and highly qualified.

In the autumn of 1933, she passed the professional examination for higher library service with top marks – a qualification that could have marked the beginning of a permanent library career. However, in the spring of that same year, the Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service had come into effect. Because of her mother’s Jewish heritage, Modrze was classified as “non-Aryan” according to Nazi racial laws and was excluded from employment. This abruptly put an end to her newly begun career in the library service.

In 1934, a new opportunity arose for her: she gained a position at Corpus Christi College in Oxford as a research assistant on the major project Codices Latini Antiquiores, led by the palaeographer E. A. Lowe, which focused on cataloguing early medieval Latin manuscripts. Modrze worked primarily on German holdings and gained scholarly recognition; however, her position remained insecure, and her long-standing health problems worsened.

After a year, she had to return to Berlin due to illness. Because of both her health and the political situation, a return to library service or an academic career was impossible. Officially, Modrze was considered “not professionally active” and lived in her mother’s household. On August 14, 1938, Annelise Modrze died at the age of only 36 at Westend Hospital in Berlin.

Illustrations:

Portrait of Annelise Modrze (ca. 1931)

Annelise Modrze, On the Problem of Writing (Dissertation), Breslau 1930. Front page and curriculum vitae.

Stolperstein Annelise Modrze in front oft the Staatsbibliothek Unter den Linden 8. Foto: A. Beser.

The German source text was translated with the assistance of ChatGPT and then revised for accuracy and style.

Library History from 1800-1945

Library History I

How did the library develop between 1800 and 1914?

Information on the library’s history before 1800 can be found at the Kulturwerk (opening hours: Wed–Sun 10 a.m.–6 p.m., Thu 10 a.m.–8 p.m.; see also https://stabi-kulturwerk.de/

1800: In the 19th century, the Royal Library began its rise to become the most important and modern library in Prussia. The acquisitions budget was doubled, and through a targeted acquisition program, the Royal Library developed into a comprehensive research library. By 1840, its collection comprised 325,000 volumes and over 6,000 manuscripts.

1842 : Founding of the Music Department

1842-1881: Development of the universal, hierarchically structured subject catalogue, one of the most important cataloguing systems of the 19th century

1859 : Founding of the Map Department

1873: The Egyptologist Richard Lepsius becomes head of the library (until 1884)

1885: According to the 1885 statute, the Royal Library was to collect German literature as completely as possible and foreign literature selectively, making it accessible. This marked the beginning of its development into a modern academic universal library. The acquisitions budget was significantly increased, and work began on creating an alphabetical card catalogue.

1886: The classical philologist August Wilmanns becomes library director (until 1905).

Founding of the Manuscript Department

1900: Around the turn of the century, the Royal Library had become the largest and most efficient library in the German-speaking world in terms of both holdings and usage (collection: approx. 1.2 million volumes).

1905: The theologian Adolf von Harnack becomes library director (until 1921)

Illustrations:

The Royal Library (so-called “Kommode”).

Circulation Desk

Office of the Manuscripts Department

Büchersaal zweiter Stock.

Reading Room, Courtyard Side

The German source text was translated with the assistance of ChatGPT and then revised for accuracy and style.

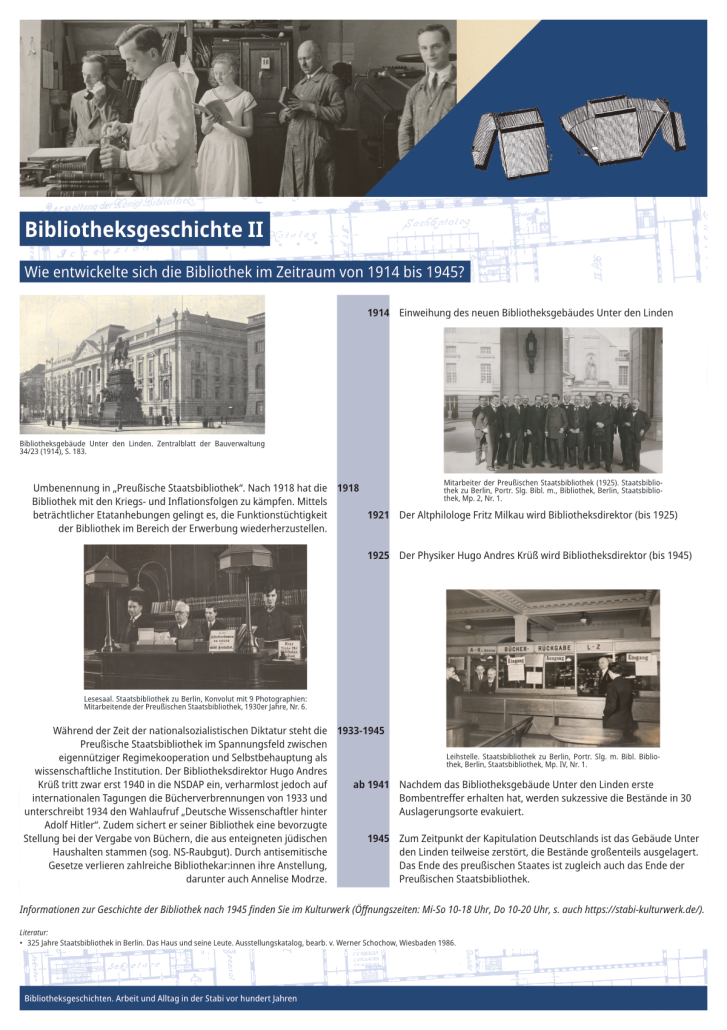

Library History II

How did the library develop between 1914 and 1945?

1914: Inauguration of the new library building Unter den Linden.

1918: Renamed as the “Prussian State Library.”

After 1918, the library struggled with the consequences of war and inflation.

Through significant budget increases, it was able to restore its functionality in the area of acquisitions.

1921: The classical philologist Fritz Milkau becomes library director (until 1925).

1925: The physicist Hugo Andres Krüß becomes library director (until 1945).

1933-1945: During the period of Nazi dictatorship, the Prussian State Library found itself caught between self-serving cooperation with the regime and self-assertion as a scholarly institution.

Library director Hugo Andres Krüß did not join the NSDAP until 1940, yet he downplayed the 1933 book burnings at international conferences, and in 1934 he signed the appeal “German Scientists Support Adolf Hitler.”

Moreover, he ensured that his library received preferential access to books confiscated from dispossessed Jewish households (so-called Nazi-looted books).

Due to antisemitic laws, numerous librarians lost their positions — among them Annelise Modrze.

From 1941 onward: After the library building Unter den Linden sustained its first bomb damage, the collections were gradually evacuated to 30 different storage sites across the country.

1945: At the time of Germany’s surrender, the building on Unter den Linden was partially destroyed, and most of the collections had been relocated.

The end of the Prussian state also marked the end of the Prussian State Library.

Illustrations:

Building of the State Library (1914)

Staff off the Prussian State Library (1925)

Reading room

Lending desk

Information on the library’s history after 1945 can be found at the Kulturwerk (opening hours: Wed–Sun 10 a.m.–6 p.m., Thu 10 a.m.–8 p.m.; see also https://stabi-kulturwerk.de/

The German source text was translated with the assistance of ChatGPT and then revised for accuracy and style.

Schooling and Education

What level of education did the library staff have?

Access to education around 1900 was strongly shaped by social background, gender, and regional structures. Most children initially attended the eight-year elementary school (Volksschule), where they acquired basic skills in reading, writing, arithmetic, and religion. Both boys and girls attended elementary school – though usually in separate classes and sometimes with different emphases. For children from working-class or rural lower-class families, schooling typically ended with the completion of elementary school, as financial and/or social constraints prevented attendance at higher-level schools. For example, library servant Friedrich Selle notes in his biography that he left school at the age of fourteen and was subsequently trained in household and agricultural work before entering military service.

Boys from middle-class families often attended advanced schools such as humanistic gymnasiums, scientific secondary schools (Realgymnasien), or upper-level secondary schools (Oberrealschulen) without classical languages. In contrast, girls from the middle class in the late 19th century could only attend so-called “Higher Girls’ Schools,” which offered instruction in foreign languages, music, and handicrafts but not in classical languages or natural sciences. The only further educational path after the girls’ school was attendance at a teachers’ training seminar. It was only from 1908 that girls could regularly obtain the Abitur and enroll at universities across the German Reich. Nevertheless, many middle-class families still considered higher education for daughters risky, fearing it might conflict with societal expectations and reduce marriage prospects.

Library secretaries Emmy Tillmanns and Charlotte Schmidt – daughters of a gymnasium teacher and a senior civil servant, respectively – followed this typical path for middle-class girls: they attended elementary school, a higher daughters’ school (Schmidt) or pursued private education (Tillmanns), and then completed the three-year teachers’ seminar. They also prepared for their careers through office courses and, in Schmidt’s case, by attending university lectures.

University studies remained largely reserved for sons of the educated middle class. Women were only granted the right to enroll in universities across the German Reich in 1908/09 – a milestone achieved largely through the efforts of the bourgeois women’s movement. After World War I, the overall number of university students increased significantly. Female students were often teachers seeking qualifications for higher teaching positions. However, married women still lost their jobs until 1920, when the so-called celibacy requirement was abolished. From 1920 onward, women were also allowed to pursue habilitation, opening the path to an academic career, although female professors still remained rare for a long time.

Librarian Carl Georg Brandis followed a typical middle-class educational path: private tutoring, gymnasium, study of classical philology, and a doctorate in Latin linguistics. Trainee Annelise Modrze was able to attend a lyceum in 1921 and obtain her Abitur. She also studied classical philology and earned her doctorate in 1930 with a dissertation on Script systems—an interdisciplinary work combining philology, philosophy of language, and semiotics at a time when the term “interdisciplinary” was not yet widely used. Both Brandis and Modrze continued to publish numerous scholarly contributions on philological and historical topics while working in the library.

With the Nazi seizure of power in 1933, the educational landscape deteriorated fundamentally. In particular, the education and professional work of women were politically restricted and ideologically devalued. The proportion of female students fell by about a quarter by 1938/39, and the number of female doctoral candidates also declined significantly. Universities were brought into line (Gleichschaltung), access became politically controlled, and academic careers were increasingly ideologically determined. From this point onward, Modrze was excluded from academic work due to her Jewish family background.

Illustrations:

Postcard: “Higher Girls’ School, Matthieustraße 33”

University of Berlin between 1890 and 1900

The German source text was translated with the assistance of ChatGPT and then revised for accuracy and style.

Selection of the library staff’s academic publications

- Modrze, Annelise (1901): Zum Problem der Schrift. Ein Beitrag zur Theorie ihrer Entzifferung, Breslau

- Wissowa, Georg (Ed.) (1890-1980): Paulys Realencyclopädie der classischen Altertumswissenschaft, Stuttgart: Metzler (Brandis‘ article)

- Wissowa, Georg (Ed.) (1890-1980): Paulys Realencyclopädie der classischen Altertumswissenschaft, Stuttgart: Metzler (Modrze’s article)

- Brandis, Carl Georg (1881): De aspiratione latina quaestiones selectae (Dissertation), Bonn

Librarian Professions

Librarian Professions

How was the work in the library organized?

Around 1900, the staff of a large scientific library was made up of various groups of employees organized in a hierarchical structure. At the top stood the library’s management, which in the Royal Library consisted of the Director General and the department directors. They were responsible for the library as a whole and oversaw the organization and management of its work processes.

The academic staff consisted of civil servants who held permanent, secure positions: the senior librarians, librarians, and assistant librarians. They were responsible for core library tasks such as selecting and purchasing books, recording new acquisitions (accession), cataloguing, organizing user services (loan and reading room operations), and managing relations with booksellers and bookbinders.

They were supported in these duties by personnel who were not civil servants: on the one hand, by volunteers who completed a two-year library training program, and on the other hand, by auxiliary workers who were not permanently employed but worked for a daily wage.

Another group consisted of the so-called sub-officials, who did not have an academic education. Within this group, a distinction was made between clerks (secretaries, office assistants), who handled office tasks such as copying documents, processing invoices, organizing files, and keeping inventory lists, and servants, who were responsible for retrieving and shelving books, packing shipments, stamping newly acquired books, running errands, as well as heating and cleaning the library premises.

The question of whether “librarian” was an independent profession or not was debated for a long time. In the 18th and early 19th centuries, it was quite common for university lecturers or other scholars to also manage libraries alongside their academic duties.

However, the view increasingly prevailed that librarianship constituted a distinct profession. This development was supported by the emergence of professional conferences and specialized studies, as well as the introduction, in the 1890s, of a two-year traineeship and a professional examination in librarianship as prerequisites for entering the academic library service.

To qualify for such a traineeship, candidates already had to hold a university degree. Because of its size and academic orientation, the Royal Library soon became the most important training library in Prussia.

Aspiring academic librarians often began their careers as auxiliary workers, initially performing simpler supporting tasks before being promoted to library assistants and later to assistant librarians, taking on more complex responsibilities.

With their promotion to the position of librarian, they assumed independent responsibility for professional duties such as the acquisition and cataloguing of books and also supervised auxiliary staff and trainees.

Illustrations:

Hierarchy of Professional Groups in the Royal Library (as of 1906)

Participants at the 8th Librarians’ Conference in Bamberg (1907).

Alphabetical Main Catalogue. Album “The Royal Library 1905.”

Periodicals Room

Librarian (ca. 1931)

Periodicals Acquisition (ca. 1931)

The German source text was translated with the assistance of ChatGPT and then revised for accuracy and style.

Women in Librarian Professions

What role did women play in the library?

While library staff in the 19th century was almost exclusively male, from around the turn of the century, women increasingly began working in libraries. Initially, they were employed as female auxiliary workers to support the academic librarians, performing tasks that required a good education but not a formal degree – matching the educational opportunities available to many women from middle-class backgrounds. This made such positions a viable option for women who wanted or needed to work.

However, these were precarious employment conditions: female auxiliary workers could be dismissed at short notice, had no entitlement to a fixed salary, and had very limited legal protection in the workplace. A significant step toward professionalization was the opening of the first library schools for women in 1900, and another milestone was the introduction of a diploma examination for the library service in 1909, which assessed professional, linguistic, and organizational skills.

Together with reports from library directors Johannes Franke (University Library Berlin) and Adolf von Harnack (Royal Library in Berlin) from 1908 and 1910, this laid the foundation for creating civil service positions for female employees. In 1911, the first female library secretaries could be employed at the Royal Library, including Emmy Tillmanns and Charlotte Schmidt.

By 1908, it is estimated that around 200 women were working in German libraries. Many of them published articles on their work. For example, in 1909, Emmy Tillmanns wrote an article titled “How Are Our Female Colleagues Trained?” discussing the situation of women in library service. Such contributions not only promoted the profession but also critically highlighted its downsides, including limited advancement opportunities, low pay, and structural discrimination.

The desire for exchange and mutual support led to the founding of the “Association of Women Working in Libraries” in Berlin in 1907, a formal interest group chaired by Emmy Tillmanns from October 1907 to autumn 1908. The association focused on advisory services, job placement, and advocating for higher training standards for female librarians. As early as 1908, the association called for the Abitur (university entrance qualification) and a three-year training program as prerequisites for the intermediate library service, as well as the admission of women to higher library service. The association grew from 90 members in its founding year to over 400 members organized in various local groups by 1912/13.

With the Reich Constitution of 1919, the professional equality of women was legally established. Subsequently, the Federation of German Women’s Associations (Bund Deutscher Frauenvereine) called on the responsible ministry, among other things, to grant women access to the academic library service and to pay them the same salaries as unmarried male civil servants.

Formal admission of women to higher library service took place in 1921. However, in practice, access remained difficult, as male applicants were often given preference. Between 1921 and 1938, only 45 women obtained a traineeship position. One of them was Annelise Modrze, who completed her traineeship from 1931 to 1933 in Wrocław and Berlin. Securing a permanent position after the traineeship was even more challenging for women.

From 1929, the philologist Käthe Iwand worked as a regular librarian at the Prussian State Library, and from 1931, the economist Klara Stier-Somlo worked as an extraordinary librarian. Nevertheless, the number of women working in higher library service remained very low. After the Nazi rise to power, career prospects for women in higher library service deteriorated further: from 1938 onward, women were only admitted to traineeships if no suitable male applicants were available, and civil service positions in higher service were generally no longer to be awarded to women.

Illustrations:

One of the first training courses for library service (ca. 1908).

Union Catalogue and Information Office (1921): Half of the staff were women, including two library secretaries, seven female auxiliary workers, and one secretarial assistant.

Subject Catalogue (1933): Among the staff were one of the first female academic librarians, Käthe Iwand, and a female auxiliary worker.

The German source text was translated with the assistance of ChatGPT and then revised for accuracy and style.

Emmy Tillmanns - a woman librarian’s perspective

- Tillmanns, Emmy (1909): Wie werden unsere Kolleginnen ausgebildet?, in: Blätter für Volksbibliotheken und Lesehallen, Leipzig, 10. Vtg., No. 5 & 6, p. 88-94

- Tillmanns, Emmy (1911): Die Bibliothekarin, in: Die Welt der Frau, Leipzig, Vtg.. 1911, p. 667-668

What does gender equality work actually involve?

The roots of gender equality work in Germany reach back to the women’s rights movements of the 19th and early 20th centuries. A decisive legal milestone was the Basic Law of 1949, which states in Article 3, Paragraph 2: “Men and women shall have equal rights.” Since its amendment in 1994, the state has been explicitly obliged to promote the actual implementation of gender equality and to eliminate existing disadvantages. On this basis, numerous laws, programs, and institutions have been established to support equality between women and men.

In the public sector, gender equality work is especially well established. Its foundation is the Federal Gender Equality Act (Bundesgleichstellungsgesetz, or BGleiG) of 2001, along with corresponding state-level gender equality laws, which apply to libraries, universities, and other public institutions. These laws require the appointment of gender equality officers who ensure that women and men are hired, promoted, and supported equally in their professional development. Gender equality work is not only understood as a reaction to inequalities but as an active process of shaping structures: it aims to change systems, raise awareness, and secure fair working conditions.

Equal Opportunities for All?

The Federal Gender Equality Act (BGleiG) obliges public employers to promote gender equality between women and men. However, it is based on a binary understanding of gender and thus does not adequately take non-binary individuals into account.

Although the General Equal Treatment Act (AGG) protects all employees from discrimination on the basis of gender, it offers fewer concrete tools for compensating for existing structural disadvantages. In recruitment processes, this can result in non-binary applicants being effectively disadvantaged, as the support measures under the BGleiG do not apply to them.

Gender Equality Work at the Berlin State Library

Since 2024, a new gender equality plan has been in effect at the Berlin State Library. Its goal is to reduce existing inequalities and to further build upon progress already achieved. The focus is on improving the compatibility of family, caregiving, and work for all employees, as well as the targeted promotion of women into leadership positions.

The plan includes specific measures such as supporting part-time employees and ensuring gender parity in department leadership roles. A project group oversees the implementation of the equality plan and reviews progress on an annual basis.

As part of our exhibition project, we spoke with the former Deputy Gender Equality Officer of the Berlin State Library, Tatjana von Schoenaich-Carolath. The interview was conducted by Lilli Waldmann and can be listened to here:

The German source text was translated with the assistance of ChatGPT and then revised for accuracy and style.

Living conditions in Berlin

Where did the library staff live?

Around 1900, Berlin experienced rapid growth: the number of inhabitants in the area that would later become Greater Berlin rose from about 932,000 (in 1871) to about 4 million (in 1920). The suburbs of Berlin grew much faster than the old city center. While in 1871, 90% of Berlin’s population still lived in the old inner city, by 1919 it was only 50%. In contrast, Charlottenburg’s population skyrocketed from 20,000 (in 1871) to 309,000 (in 1910). Similar developments – often connected to the expansion of the transportation network and the establishment of new industries – also took place in Schöneberg, Rixdorf, Lichtenberg, and Steglitz.

Wealthy families who had previously lived in the old city center now moved westward: the Kurfürstendamm district in Charlottenburg, the Bavarian Quarter in Schöneberg, and parts of Friedenau, Steglitz, and Wilmersdorf—with their new, comfortable apartment buildings – became popular residential areas for the upper middle class. In the outskirts, prestigious villa colonies emerged, such as in Groß-Lichterfelde. In the poorer northern and eastern districts and suburbs, including Reinickendorf, Pankow, Lichtenberg, Rixdorf, and Stralau, large tenement blocks with numerous courtyards were built. Since housing construction was almost entirely in private hands, many very small apartments were built – yielding the highest rental profits – alongside luxurious flats for wealthy tenants. However, the strong demand for medium-sized, affordable housing remained unmet, which significantly contributed to the housing shortage and the often very poor living conditions of the lower-income population.

These socio-topographical developments are also reflected in the places of residence of the staff of the Royal Library. An analysis of all employees’ addresses listed in the Royal Library’s annual report for 1906 shows that the districts of Berlin-West (14% of employees), Berlin-Northwest (10%), and Charlottenburg (10%) were the most common places of residence.

This can be further specified by occupational groups: among directors, senior librarians, and librarians, Berlin-West and Groß-Lichterfelde rank first (each 21%), followed by Charlottenburg and Schöneberg (each 11%). At the lower end of the library hierarchy – secretaries, clerks, and servants – Berlin-Northwest ranks first (15%), followed by Berlin-North (13%). Among assistant librarians, interns, and auxiliary workers, Charlottenburg ranks first (19%), followed by Berlin-West (17%) and Berlin-Northwest (11%). This may be due to the heterogeneity of this group: these individuals, who did not yet hold permanent civil service positions, could later occupy very different posts – from director to secretary.

The percentage composition of occupational groups within each district also confirms these observations: the western and southwestern districts and suburbs were inhabited exclusively or predominantly by directors and librarians, while in the north and east, secretaries and servants were much more strongly represented. Berlin-Northwest, Steglitz, and Wilmersdorf were more mixed. It remains to be examined whether a social stratification can be observed within the districts themselves or even within the apartment buildings (front and rear buildings, main floors and attic apartments).

Illustrations:

Districts and suburbs of Berlin with the respective percentages of employees of the Royal Library residing there in 1906, from the occupational groups “Directors and Librarians” (blue), “Assistants” (green), and “Secretaries and Servants” (red).

Districts and suburbs of Berlin with the number of employees of the Royal Library residing there in 1906.

The German source text was translated with the assistance of ChatGPT and then revised for accuracy and style.

About the Seminar

Making the Past Visible

Library Stories – A Student Exhibition

The exhibition “Library Stories. Work and Life in the Stabi 100 Years Ago” was created as part of a project seminar. In the summer semester of 2025, a group of students from the Cultural Studies (BA) and Comparative Literature and Art Studies (MA) programs at the University of Potsdam met once a week in the Oxford Room of the Staatsbibliothek (Berlin State Library) to explore the history of Berlin and the library around 1900.

The central source for the seminar consisted of historical personal files of former library employees of the Stabi – a whole collection of biographies, employment records, letters, medical certificates, and vacation requests. During the seminar, students learned to read and transcribe historical handwriting and, in doing so, researched the curricula of five exemplary employees – their social background, education, interests, and opportunities within the library a century ago. The exhibition you see here is the result of these investigations.

Easier Legibility – The Use of Automatic Handwriting Recognition

The archival documents processed in the seminar were not only transcribed “by hand” but also processed using a tool for Handwritten Text Recognition (HTR). This works as follows:

-

The digitized personal files are uploaded into the tool.

-

The tool performs automatic layout segmentation – in other words, it detects where text appears on the page and marks the text lines.

-

The text can then either be recognized automatically or transcribed manually. In the background, the recognized text is mapped to the pixel regions of the corresponding lines in the digital image, allowing precise alignment between the transcription and the original document.

This process forms the basis for training AI models for automatic text recognition. Using the transcriptions, the model “learns” what the letters in that handwriting look like. When the trained model is later applied to a similar text (for example, from the same hand), it can “recognize” the letters again.

Documents like personal files are particularly challenging for automatic text recognition because they contain a wide variety of handwriting styles. Our transcriptions therefore also contribute to improving automatic text recognition in general – by publishing the data and making it available for research.

But it is not only researchers who benefit from these transcriptions. They can also be imported into other applications, such as the Digitized Collections of the Staatsbibliothek. This makes the documents accessible to everyone — including those who cannot read historical handwriting. Moreover, the transcribed files can now be searched in full text, potentially leading to new cross-document discoveries.

Participants in the Exhibition Project

Project lead:

Nicole Eichenberger (Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin) and Maria Weilandt (University of Potsdam)

Seminar participants:

Elisabeth Badru, Fiona Mara Bastian, Amanda Beser, Anne Bockisch, Carlotta Egemann, Marie Eggebrecht, Evelina Elke Graffmann, Leoni Holst, Lelo Kalmus, Tobias Metschies, Janina Obst, Johanna Preuße, Antonia Przyborowski, Mandy Röser, Emma Schweinsberg, Jessica Unger, Lilli Waldmann, Amelie Weinberger

Interns:

Tobias Metschies, Emma Schweinsberg

We would like to thank all colleagues at the Stabi who supported us in this project, in particular: Robert Giel, Marie Grotewohl, Vanessa Mohler, Sarah Müller, Lea Nohr, Felicitas Rink, Vincent Schmidt, Tatjana von Schoenaich-Carolath, Carly Taylor-Mittmann, and Christine Theuerkauf-Rietz.

Illustrations:

Participants of the seminar in the Stabi’s Oxford Room

The „eScriptorium“ tool

View of Charlotte Schmidt’s file in the Stabi’s digitalized collection

The German source text was translated with the assistance of ChatGPT and then revised for accuracy and style.

Further Reading

Mieke Bal (2006): „Sagen, Zeigen, Prahlen“, aus: dies.: Kulturanalyse, Frankfurt/Main: Suhrkamp, S. 72-116

Ihr Kommentar

An Diskussion beteiligen?Hinterlassen Sie uns einen Kommentar!