Uncertainties in the Archives

This guest post by Firmin Forster, Privam Goswami Choudhury, Katharina Süberkrüb and Emily Ziegler-Efimova explores the project “Uncertainties in the Archives,” which was recognized with the Audience Award by participants of the Open Cultural Data Hackathon “culture.explore(data)” on 7-8 October 2025 at the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin. The hackathon made available datasets from across the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation and the Libraries and Museums at Oxford University.

Over the course of the two-day hackathon culture.explore(data) in early October at the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, we explored uncertainties and ambiguities in geographical data provided by the Ethnological Museum in Berlin. Our data (Culture Translocated: Entities in the Ethnological Museum – Stabi Lab) consists of semi-structured information about people and corporations connected to the museum until the year 1950.

Collections like those of the Ethnological Museum in Berlin were shaped within colonial frameworks, and the ways in which places, cultures, and individuals were recorded often reflect Eurocentric perspectives and power dynamics. Therefore, provenance information, naming practices, and geographical attributions can be biased, incomplete, or distorted. Recognizing these biases is essential to interpreting and processing such data because they influence how we reconstruct, represent, and understand cultural histories today.

The process of confronting the colonial provenance of many such objects in our cultural institutions depends on our ability to re-interpret and re-process the data available to us. This form of interpretation requires us to understand that archives are, as Diana Taylor points out in her book The Archive and the Repertoire (2003), mediated spaces: By highlighting the original data not as immutable calcified records of the past but as interfaces that can enrich our own research in the present moment is where we began our exploration of the Ethnological Museum dataset. Initially, we were trying to think of ways in which we could visualise the changing sites of an object as individual trajectories that would lead to Berlin. However, we were also dealing with the uncertainty of the archives where dates were blurry and the simple act of locating an object in a place was difficult.

Projektbesprechung während des Hackathons „culture.explore(data)“ an der Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin (Foto: Hagen Immel)

We, therefore, started to standardise the geographic locations in our data using a simple Python script. While examining our data more closely, we noticed that some places appear with many different spellings (e.g. Frankfurt vs. Frankfurt a.M. vs. Frankfurt am Main) or include markers of uncertainty (e.g. question marks). Digging deeper revealed more complex challenges that we could not address automatically:

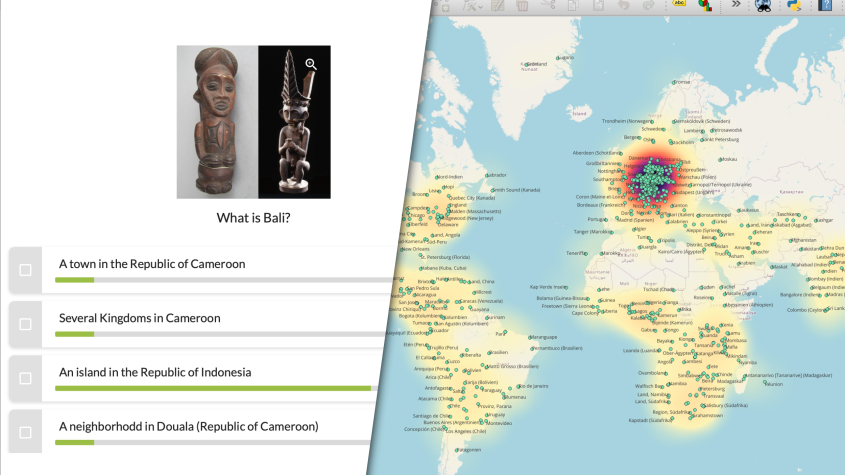

- Same name – different place: A single name refers to different geographical entities, e.g. Bali, which represents an island in Indonesia as well as a town and neighbourhood in modern Cameroon.

- Same place – different name: Different place names may refer to the same geographical entity due to varying spellings across languages (e.g. Wrocław and Breslau) or changes in name or attribution over time (Lahore (Pakistan) / Lahore (Indien) / Lahore (Britisch-Indien))

- Different levels of precision: Some names refer to cities (Berlin), while others refer to broader regions (Südbrasilien) or former colonies (Deutsch-Südwestafrika)

Using our expertise in this field, we combined place names referring to the same location into a single entry within the available timeframe of the hackathon. To obtain corresponding geographical information in a computer-readable format, we used the GeoNames API and visualized all the data points we could find as a heatmap using QGIS. The resulting map shows a noticable hotspot in central Europe, especially in today’s Germany. This is to be expected as we included all place names in the data, which not only include Aufenthaltsort (place of stay) or Sammelgebiet (collection area) but also Geburtsort (place of birth) and Sterbeort (place of death). To focus closer on the aspect of collection, a further differentation of the data and a restriction to collection areas is needed.

We see each visualisation as an act of interpretation and we are aware that during this process, we inevitably introduced additional biases, i.e. interpretations of data. Neither was our manual data cleaning perfect, nor did the automatic retrieval of geocoordinates work without errors. Indeed, we did not get coordinates for around 58,5 % of the places in the data; places which are – presumably – much more difficult to identify. Because of the inability to show these places without coordinates on a map, this leads to a distortion of the point distribution and the heat map. We, therefore, acknowledge that our final map is full of uncertainties as a result of human- and computer-based work with this ambiguous and uncertain data, and we would like to treat it as such.

Even though we deal with a lot of uncertainties in the process of mapping and visualising our data, we view the process of data preprocessing as a method to explore (cultural) data. It allows us to gain initial insight into its structure and challenges; changing our perspective of the uncertainty in the archives from a difficulty into a characteristic of humanities data that we chose to highlight.

To present these findings, we created a fun little quiz named „GuineaPick“ to allow the audience to experience the difficulties of mapping historical geographical data themselves. The quiz shows a list of all the places designated as „Guinea“ in the data and asks the players to identify them on a map. The difficulties are (again) that some names refer to the different places (all of them are named somewhat Guinea) while some places have had different names over time (Portugiesisch-Guinea and Guinea-Bissau), all while dealing with different levels of precision (Bolama (Guinea-Bissau) is an island and part of Guinea-Bissau). In the special case of „Guinea“, they are located next to each other like Guinea and Guinea-Bissau.

Our project highlighted the importance that both technology and human ability play in understanding the archives and the past. While technology and automated processes allowed for such large amounts of data to be handled and visualised, it alone would not be able to contextualise the data in this project to make informed decisions about how to properly geolocate the provenance of the different artefacts of this collection, for instance, whether to assign an artefact coming from Bali to Bali, Indonesia or Bali, Cameroon. Humans and their abilities remain at the centre of knowledge creation; they are needed and cannot be replaced by algorithms, especially in the realm of digital humanities, where the complexities of human reasoning and intelligence can be combined with the powers of computers, algorithms, and models to create new insights that broaden our understanding of the past.

Project results: Uncertainties in the Archive

Learn more about the Stabi Lab:

Uncertainties in the Archive

Uncertainties in the Archive

Ihr Kommentar

An Diskussion beteiligen?Hinterlassen Sie uns einen Kommentar!