Imagined Hegenomies: Colonialist Literature for German Youth during the Weimar Republic

Gastbeitrag von Prof. Luke Springman, Bloomsburg University

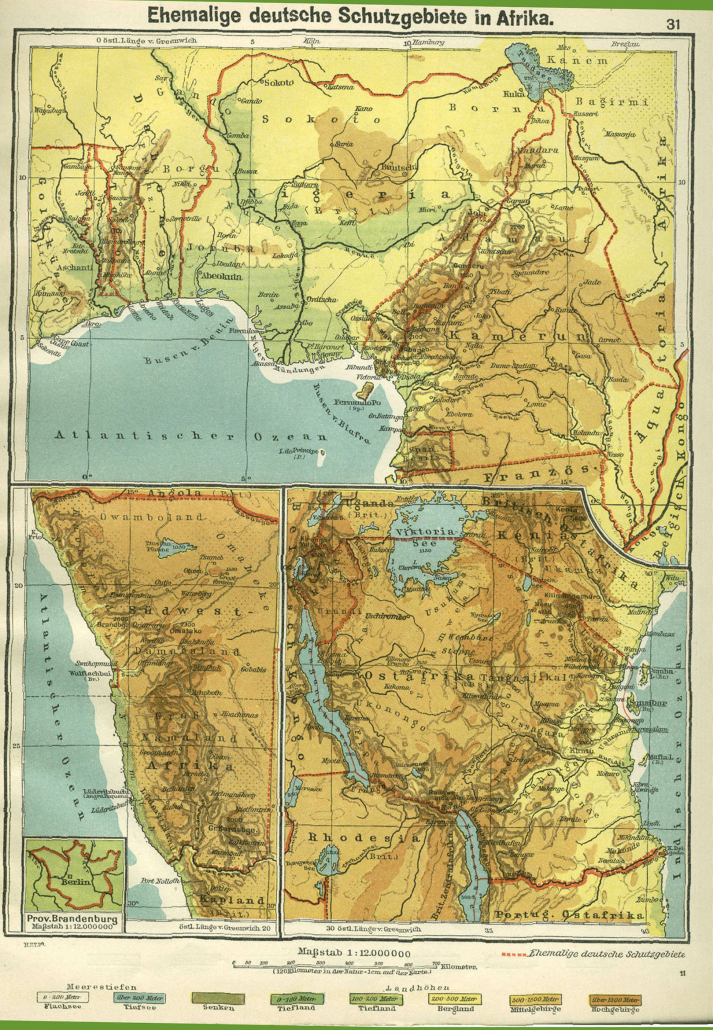

A „flood“ of popular literature about Africa swept the book market in Germany after it had irretrievably forfeited all its colonial possessions at the end of World War I. From 1884 to 1914, Germany had become the world’s third or fourth largest colonial power (depending whether one referred to land mass or to population); in Africa, Germany had claimed territory in what is today Togo, Cameroon, Tanzania, and Namibia. Overseas possessions, however, affected the German economy and culture little in comparison with the impact colonies had on England and France. Nevertheless, a dedicated minority of influential Germans devoted serious and sustained efforts after 1918 to keep alive the desire for empire in Germany. Their influence precipitated a surge of colonialist literature in the mid-1920s that maintained a strong presence in popular culture well after the end of the Weimar Republic (1918-1933), despite the indifference the general public held toward reclaiming colonies. At the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, I have studied colonialist African literature for young people by over thirty authors, and that represents only a selection.

Josef Viera (1890-1970) was one of the most prolific authors of colonialist literature. Viera served in the German defense force in German East Africa during World War I. Starting in 1925, he also edited a popular series of collected stories „Aus weiter Welt“ (From the Wide World) for the prominent publisher of young people’s literature Enßlin & Laiblin. See: https://www.namibiana.de/namibia-information/lexikon/begriff/schriftenreihe-aus-weiter-welt-ensslin-laiblin-verlag.html. – Vol. 5: Karl Angebauer, Afrikanische Siedlergeschichten, 1929. – (Personal Collection)

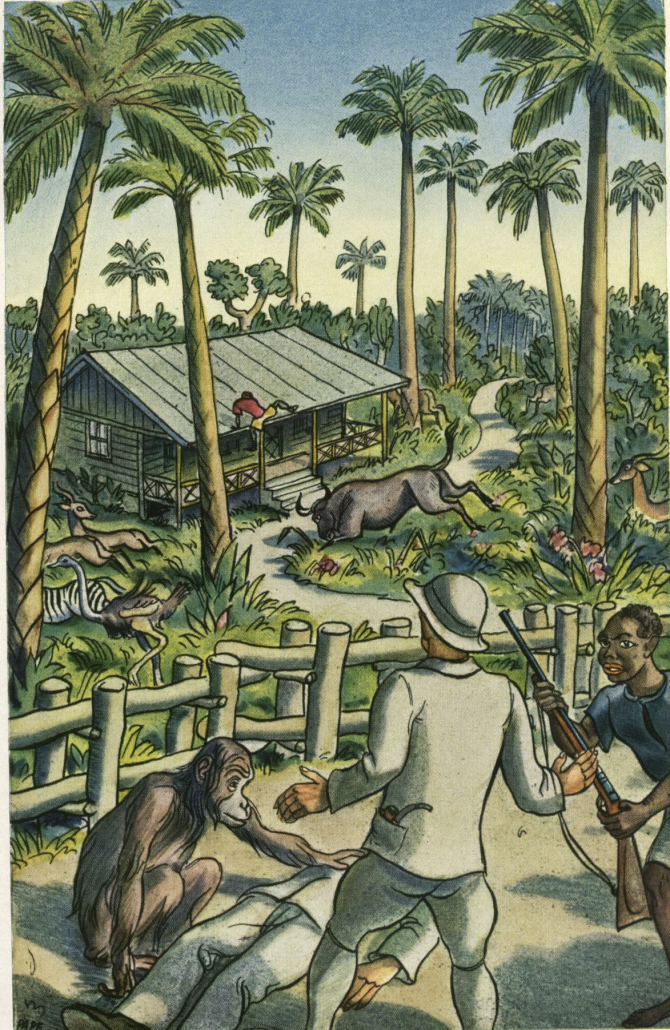

Else Morstatt (1880-1930), Hinter dem großen See. Eine Erzählung aus Deutsch-Ostafrika. (Beyond the Great Lake. A Story out of German East Africa) Stuttgart: Thienemann, 1927. Frontispiece. Many of the authors of colonialist literature, such as Morstatt, had actually lived in German colonies. – Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin. Signatur: B VIII, 13218 KJA

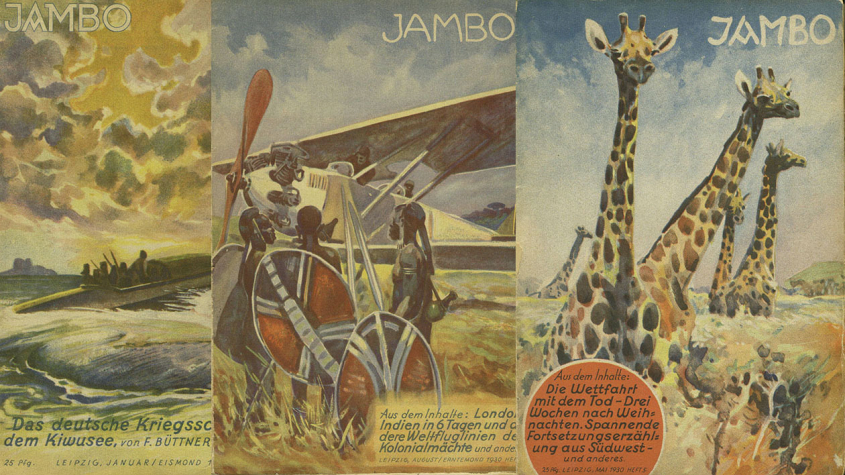

In the 1920s, young people’s literature relating to the former German colonies represented a significant part of a larger output of propaganda that was produced to cultivate „den kolonialen Gedanken“ (the colonial thought, that is, the colonialist mindset) and preserve the memory of imperial claims abroad. „Der koloniale Gedanke“ and „die Erinnerung an die deutschen Kolonien“ (remembering the German colonies) comprised two pivotal concepts in colonialist rhetoric that aspired to integrate hegemony as a component of German national identity for the younger generation of Germans. German colonialist societies under the umbrella organization Deutsche Kolonialgesellschaft (DKG, German Colonial Society) gained significantly in membership and influence during the Weimar period, establishing themselves as the bastion of Weimar revanchism. Under the auspices of the DKG, the monthly magazine for young people Jambo appeared from 1924 to 1942, which served as the organ for the colonialist youth movement. Besides the colonial societies, a wave of Africa books and films propagated the memory of former colonies and cultivated the ideals for an imperialist future for Germany. Or at least those were the aspirations. Ultimately, the Weimar colonialist movement failed to imprint Africa on German collective national identity, and few works of colonialist literature are remembered.

Yet precisely in the failure of such an enormous enterprise lies a rich opportunity to investigate mechanisms of cultural memory, as understood in cultural memory studies of recent decades. Accordingly, collective memory and group mind-sets represent socially constructed orderings of past events that guide perceptions of and attitudes toward the present, while also shaping projections of the future. Africa, that is „German“ Africa, in no small way appeared in fiction, non-fiction, memoirs, films, advertising, school curricula, youth organizations, exhibitions, colonial fairs, and monuments, but still could not overcome the power of forgetting.

Two salient features of colonialist youth literature serve as points of departure for the present investigations, which one may formulate as „context“ and „text“. Context refers to the broad social and historical environment in which a work appears and which illuminates the significance of the work. For example, the film Zum Schneegipfel Afrikas (To the Snowy Peak of Africa, 1925) must be understood in relation to the expulsion of all Germans from „German East Africa“ after World War I and the subsequent lifting of the ban in 1925. The film and its companion book were therefore not merely travel documentaries, but rather powerful propaganda designed to entice Germans to settle in the British mandate Tanganyika, an initiative that the Colonial Department in the German Foreign Office was secretly funding. Moreover, this Lehrfilm (educational film) was shown in schools and to youth groups. Context provides insights into the ways colonialist literature contributed to the construction of collective memory.

On the other hand, for the present study, „text“ concerns the interplay of words and images. Most of the colonial books for young readers were illustrated and many of them richly so. Some of the authors were also artists and photographers who illustrated their own books. A number of the books also, as with Zum Schneegipfel Afrikas, appeared as companion texts for films. Images do not merely give a visual depiction of the written words, but can also interpret, expand on, even contradict what the author writes. Photographs, drawings, painting, maps, and cinematic sequences also augment emotional responses to the narrative.

Atlas für die Hamburger Schulen. Braunschweig: Verlag Georg Westermann, 1930. Every map of Africa in German school atlases showed Togo, Cameroon, Southwest Africa (Namibia), and Tanganyika as the former German „protectorates“ with their former names, such as Deutsch-Ostafrika (German East Africa). – Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin. Signatur: 4° Kart. B 2262/13<1930>

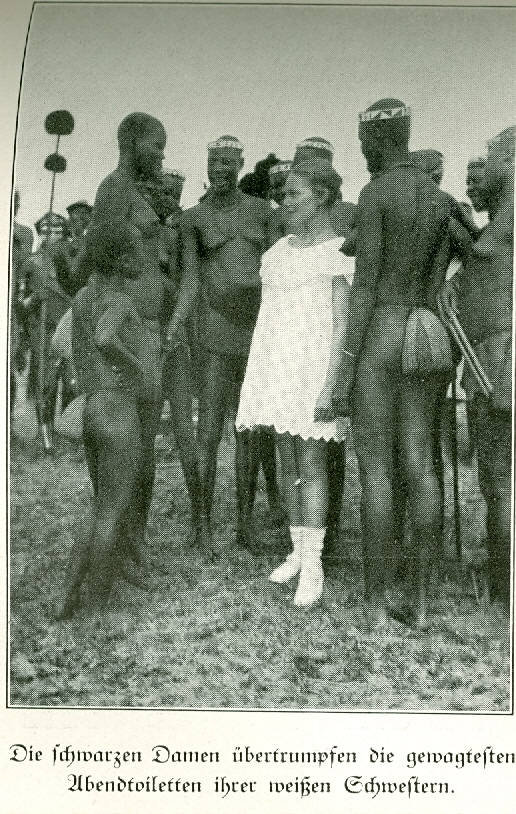

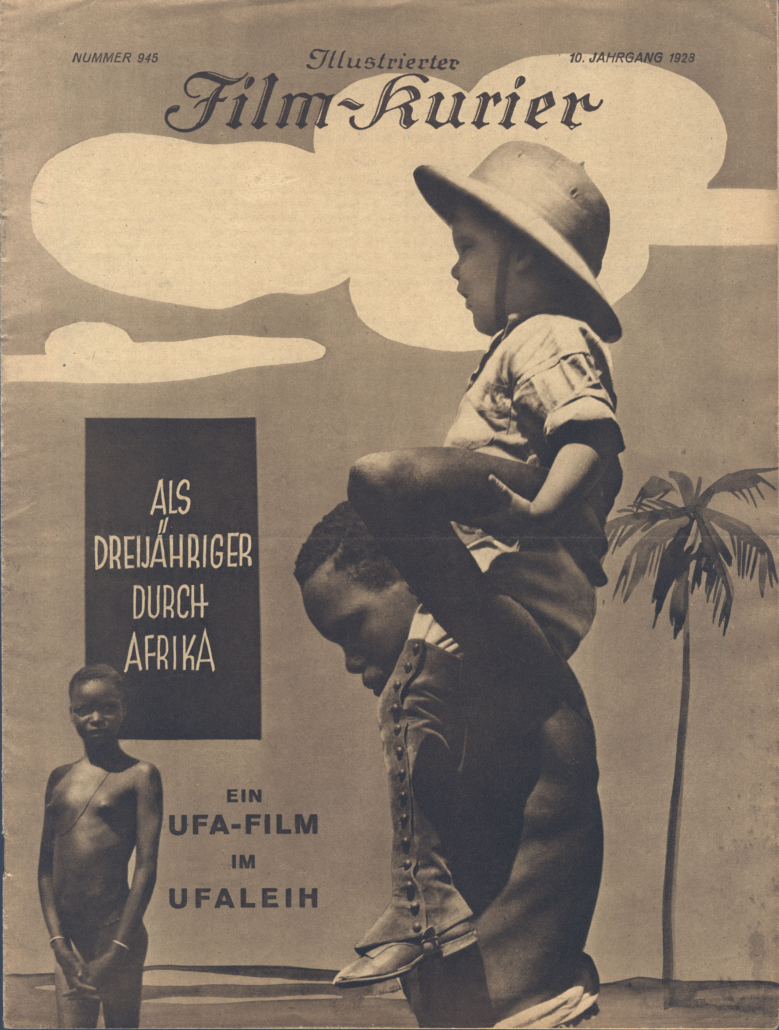

As a case in point for the interplay between images and words, Colin Ross, the most famous German world traveler during the Weimar period, published a travelogue for young readers titled Mit Kamera, Kind und Kegel durch Afrika (With Camera, Kith, and Kin through Africa, 1926), one of a series of his „kith and kin“ books about traveling with his wife, daughter and son to exotic lands. Ross also created a film for young people from the large amount of footage from this trip that he did not use for his documentary film Die erwachende Sphinx (The Awaking Sphinx, 1927). The film Als Dreijähriger durch Afrika (As a Three-Year-Old through Africa, 1928) actually parodies the clichéd narratives by intrepid explorers: Ross‘ son plays the role of the intrepid adventurer on his journey from South Africa to Egypt, depicted as a romp through a fairy-tale landscape. Although the film is loosely related to the book, and seems innocuous at first blush, the written narrative, film, and photographs taken together express at once exotic allure, eroticism, and uncanny fear. For example, the encounter with a Kavirondo tribe is a significant episode in both the film and the travelogue. The innocent play between the little white boy and warriors in ceremonial costumes belies the subliminal dread and disgust Ross harbored for these people. In the children’s book, as he sets up his camera, he describes in harsh terms — excessive for a children’s book — Kavirondo women as naked and repulsive old hags in drunken stupors, closing in around him and thrusting their breasts at him in a threatening manner. As a further contradiction, a photograph in the book of Ross‘ daughter in seemingly pleasant company with Kavirondo women is at odds with the menace that the author portrays.

The task is not only to point out the blatant racism in this case, but rather to derive meaning from the combinations of texts and images as they both complement and contradict each other, then to place that meaning in a broader context of history and culture. Deeper analysis here, however, would exceed the intentions of the present account.

„The black ladies trump the most daring evening fashion of their white sisters.“ – From: Colin Ross, Mit Kamera, Kind und Kegel durch Afrika. Leipzig: Brockhaus, 1926: 96. – Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin. Signatur: Us 2178/60

„Als Dreijähriger durch Afrika“. Illustrierter Film-Kurier. Vol. 10 (1928), Number 945: cover. From: Die Deutsche Kinemathek – Museum für Film und Fernsehen. Copyright: Verlag für Filmschriften, Christian Unucka (http://www.unucka.de)

Herr Prof. Luke Springman, Bloomsburg University, war im Rahmen des Stipendienprogramms der Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz im Jahr 2018 als Stipendiat an der Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin. Forschungsprojekt: „Colonial Memory in the Youth Culture of the Weimar Republic“

Historial de la Grande Guerre - Musée de Péronne (Somme)

Historial de la Grande Guerre - Musée de Péronne (Somme) K:\IID\IID_2_Wissenschaftliche_Dienste\01_uebergreifendeAufgaben\Wissenswerkstatt\Werkstattgespraeche\2017\Arab.Handschriften\AW WG Arabistik.msg

K:\IID\IID_2_Wissenschaftliche_Dienste\01_uebergreifendeAufgaben\Wissenswerkstatt\Werkstattgespraeche\2017\Arab.Handschriften\AW WG Arabistik.msg K:\ZWR\Bildrechte\Murawski\Maerchen_2016\Wg_Maerchen_PublicDomain_Wikimedia.png

K:\ZWR\Bildrechte\Murawski\Maerchen_2016\Wg_Maerchen_PublicDomain_Wikimedia.png

CC-BY-NC-SA

CC-BY-NC-SA Normann Johanns

Normann Johanns

This blog provides Very informative content .