On an attempt to reconstruct the image of Silesian towns in the 18th century on the basis of historical cartography: Kriegskarte von Schlesien

Gastbeitrag von Prof. Monika Ewa Adamska

I’ve been conducting research in the Silesia area, which has been a historically contested region in Central Europe for many years, focusing on the transformations of its historical rural and urban structures, colonisation processes, the issues of post-war rebuilding and contemporary revitalisation processes.

For a brief introduction to the region I’ll step back to medieval times, when Silesia (German: Schlesien) was divided into many independent duchies. In the modern era, the region became successively the property of the Crown of Bohemia and the Habsburg Monarchy. As a result of the Silesian Wars in the 18th century, most of the area was incorporated into Prussia, which soon – under the rule of King Frederick II (1740–1786) – became one of the greatest powers in Europe. Since 1945 most of Silesia has been lying within the borders of Poland. The history of the region is reflected in its multicultural heritage, both tangible and intangible. Spanning ca. 40 000 km2 spread along the Oder, Poland’s second longest river, the region consists largely of agricultural and forested lowland, with a mountainous southern border. It also includes several industrial areas capitalising on its rich mineral resources. In the 17th and 18th centuries, the region was inhabited by 1–1,5 million people, nowadays the population reaches 8 million.

One of the major, invaluable sources of knowledge for historical cultural landscape reconstruction are cartographic documents. Cartography is the study and practice of making and using maps. Topographic maps are among the most useful cartographic documents. They include both landscape and landform elements and are predominantly recorded on paper. They usually comprise a multi-element work and consist of up to hundreds of map segments. These maps are not only a major source of knowledge in historical science and cultural studies, but also works of art (Medyńska-Gulij; Żuchowski).

The first official cartographic picture of Silesia was made in 1723–1733 by the Austrian lieutenant J. W. Wieland. The Prussian King Frederick II, a newly enthroned ruler of the major part of Silesia, was not satisfied with their usefulness for the military. In 1746 the monarch commissioned the work of making a new cartographic picture of the region to a military cartographer, Westphalian-born captain Christian Friedrich von Wrede, who formed a team of specialists to take measurements in the field and produce the new maps. Work over this new picture was carried out in 1747–1753. The team was stationed at the Glatz Fortress (now Kłodzko), of which Wrede was a chief engineer. The picture covered the entire region except for the central part south of the Oder. The copy of the maps prepared for the King took the form of atlases. The maps received the contemporary collective title Kriegskarte von Schlesien. Silesia did not earlier have such a cartographic document that was so large and detailed (Hanke; Janczak).

Fortunately for the posterity and science, these military maps, a unique 18th century cartographic picture of Silesia, have survived until our times. Colourful, hand-drawn originals of this picture, both the atlases ( part 1, part 2, part 3, part 4, part 5) and the overview maps form part of the cartographic collections of the Map Department of the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin (State Library at Berlin). The Map Department, a separate unit of the Library since 1859, holds an extensive cartographic collection on all continents and countries, including the region of Silesia – the subject of my scientific research.

I learnt about Wrede’s military maps during my research grants at the Herder Institute in Marburg/ Germany taken in 2015 and 2016. The colourful reproductions of some maps from atlases I saw there immediately caught my attention. I thought at that time that I would like to explore them in the future. Just a year later I realized my first research grant awarded by the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin within the Grant Program of the Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz. The project concerned spatial transformations of Silesian medieval old towns from the 18th century to 1945 and was carried out at the Map Department of the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin. It was connected with my habilitation monography on market-places, which I was working on at that time. Kriegskarte von Schlesien was amongst the most relevant sources then. In autumn 2022 I had the privilege to complete another research grant at the Map Department, this time entirely based on the King’s atlases. The project was entitled “Reconstructing the image of Silesian towns (intra et extra muros) in the 18th century on the basis of Krieges Carte von Schlesien by Christian Friedrich von Wrede”.

I’ll precede the presentation of the project and some of the initial results with a short introduction to the atlases themselves. All five volumes, with the external dimensions of 40 x 52 cm each and in folio format, are bound in red leather with gold edging (Fig. 1). The intertwined initials FR embossed in gold letters with the royal crown identify the atlas as a personal copy of King Frederick II of Prussia.

Fig. 1. Prof. Monika Ewa Adamska with one volume of the atlas “Kriegskarte von Schlesien” in the Reading Room of the Map Department. – Photo by SBB‑PK

All volumes are made up of as many as 201 sheets in total, including 195 map sheets, 5 title sheets, and 1 special sheet. Maps were drawn on a scale of 1:35 000. The town plans forming the title sheets were presented on a scale of 1:14 000. The size of a single sheet is 73 x 52 cm, of which the map itself comprises 60 x 43 cm (Lindner). All maps and town plans are orientated in the northern direction. Each map sheet is composed of an area of cartographic content and an area of the cadastral register as a vertical text strip on the right side of the sheet (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. An example of a map sheet from the atlas “Kriegskarte von Schlesien”: volume 3, sheet 18. – SBB-PK: 2° Kart. N 15060‑3 – Photo by M. E. Adamska

The five title sheets, which are a key source in my project, contain 66 town plans in total (from 9 to 18 per each) and one plan of an abandoned castle (Fig. 3). All of them are composed coherently: the town plans surround a centrally located map legend enclosed in a rectangular frame. The latter contains the title of the volume, its scale, an explanation of the symbols used and Wrede’s signature.

Fig. 3. The title sheet from the atlas “Kriegskarte von Schlesien”, volume 1. – SBB-PK: 2° Kart. N 15060‑1 – Photo by M. E. Adamska

Working with the nearly 300 years old atlases is certainly extremely exciting, but it also requires certain precautions. Before it could be examined, each of the five leather-bound parts had to be bedded on foam wedges for protection (Fig. 4). Additionally, all measurements had to be preceded by the application of a transparent foil. As mentioned above, the town plans presented on the title sheets were crucial for the project. It is worth mentioning that for some Silesian towns, this was the first plan ever in their history.

Fig. 4. One of five volumes of the atlas “Kriegskarte von Schlesien” prepared for the research, Reading Room of the Map Department. – Photo by M. E. Adamska

All 66 towns mapped on the title sheets are nowadays located within the borders of Poland, except for three situated in Czechia. They were all founded in the Middle Ages, the majority in the 13th century (90%), others in the 14th century (own work based on Weczerka). It’s important to state here that the Middle Ages were the time when most of Silesia’s towns were established as part of a broad wave of central European urbanisation. Silesian towns and cities formed a regular settlement network with centres at a distance of 15–20 kilometres. By the first half of the 14th century, about 120–130 towns and cities had been founded in Silesia, out of 5000 in the whole of Europe (Eysymontt). The municipal charter was a model for the functioning and organisation of the social and economic life of a given town. It established the rights to which the town was entitled and defined its spatial layout and the rules of parcelling. Most Silesian towns and cities adopted the model called the Magdeburg law (and its variations). Their layouts are mostly characterised by an oval shape, grid street plan, regular blocks of development, a centrally located market-place (Rynek) and city walls. In the 18th century they still remained within their city walls, rather undergoing changes than simply developing, being experienced by fires, epidemics and wars over the centuries.

The Berlin-based project “Reconstructing the image of Silesian towns (intra et extra muros) in the 18th century on the basis of Krieges Carte von Schlesien by Christian Friedrich von Wrede” is a study based on physiographic, morphological and functional analyses. The aim of the project was an attempt to reconstruct the image of Silesian towns on the threshold of the Frederician epoch, in the middle of the 18th century. This image was planned to be built mainly in terms of urban morphology and physiognomy, followed by some functional aspects included in the Kriegskarte von Schlesien. The term reconstruction is adopted here in the sense of re-creation or reimagining of something from the past, especially by using information acquired through research.

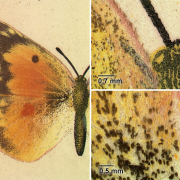

In the first phase of the project, I elaborated tabular compilations for each of the 66 towns both intra et extra muros, containing physiographic, morphological and functional characteristics, followed by cadastral information on the owners, number of burghers, farmers, horses etc. For each town I also made a comparison of its plan on a scale of 1:14 000 (title sheet) with the one on a scale of 1:35 000 (map sheet) to analyse the town in the broader area context. To prepare the tables it was first necessary to recognize all the icons used on the map, some placed in the title sheets’ legends, some not. Dozens of symbols define the maps’ content, such as road infrastructure, bridges (stone and wooden ones), postal stations, economic activity: mills, windmills, and brickyards. Based on the atlas, it is possible to collect a lot of information about sacred facilities located in the towns or in their immediate vicinity, such as Catholic and Protestant churches (symbols differ only in the location of the tower: the first one has it on the left side of the church’s silhouette, the second one on the right), monasteries, and chapels (Fig. 5). Also castles and noble residences are marked. In the legends, the locations of smaller objects such as gallows (distinguishing between wooden and brick ones, often on a hill outside the city) or wonderful views are also indicated.

Fig. 5. A part of the legend from the atlas “Kriegskarte von Schlesien”, volume 1. – SBB-PK: 2° Kart. N 15060‑1 – Photo by M. E. Adamska

There are many symbols for landscape and landform elements which are not explained in the legends, such as blocks of development (pink), other public buildings (bright red scarf), cemeteries (indicated with small crosses), running and still waters (in blue), relief features (grey hatching), marshes (marked in blue horizontal dashes) or woods (marked in light grey, symbols of trees in dark grey). Deciphering them required additional knowledge in the area of historical cartography and topographic maps. Town plans with a scale of 1:14 000 depict precisely the features of the towns’ layouts, street systems, blocks of development. They also reflect the defensive walls, mostly medieval, but also the modern star-shaped fortifications of the Silesian fortresses such as: Brieg, Glogau, Neisse (now Brzeg, Głogów, Nysa). The entire atlas is described in German, only the fords for vehicles and walkers are in French.

The first phase of my project demonstrated the accuracy of Wrede’s maps in terms of noting individual development of particular towns at the time, such as the evangelical Churches of Peace erected in the 17th century in Glogau, Jauer and Schweidnitz (now Głogów, Jawor and Świdnica) or the evangelical church in Grünberg (now Zielona Góra) completed in the 1740s on a Greek cross plan. Even such details as baroque fountains on the market-place in Schweidnitz (now Świdnica) were depicted. An interesting bit of trivia for geographers or farmers shows up here as numerous vineyards are mapped in the western part of Silesia, around such towns as Grünberg, Beuthen and Crossen (now Zielona Góra, Bytom Odrzański and Krosno Odrzańskie).

The synthesis of towns’ analyses enabled me to formulate first conclusions. Physiographic analysis revealed that nearly 80% of the 66 towns studied were located on the main rivers or minor watercourses. Analysis in the area of urban morphology allowed for specifying three layouts: regular oval, irregular oval and circle. The first two groups are represented by more than 70% of the towns, the others have a circular shape. A full or partial grid plan is predominant and can be observed in the case of most of the towns analysed. Patschkau (now Paczków) is among those with the most regular layout. I also examined the shape of market-places and specified four main ones: rectangle, quadrangle, square and elongated (Straßenmarkt). Rectangular market-places were predominant, with quadrangle and square coming next. There are only a few towns with the elongated Straßenmarkt type. Among the other forms worth mentioning is a market-place in the shape of a quarter of a circle in the town Leobschütz (now Głubczyce).

Another morphological characteristic refers to urban blocks in terms of their infill with development. The urban blocks in more than 80% of the towns were fully filled with development. In the case of the remaining towns, usually the smallest ones, I noticed some blocks partially filled with development or without development at all, with some cultivation mapped in their areas. Town defensive walls were the topic of another interesting analysis conducted. It revealed that in the middle of the 18th century, more than 70% of the towns still had medieval defensive walls, in some cases strengthened with modern elements. Modern defensive systems were present in two forms: as fortified town and as fortress. Eight towns belonged to the first group. Six fortresses comprised the second: Breslau, Brieg, Cosel, Glatz, Glogau, Neisse (now: Wrocław, Brzeg, Koźle, Kłodzko, Głogów, Nysa) (Fig. 6). They were located either on the Oder or the Eastern Neisse river. There were only a scant few small towns with no defensive walls at all.

Fig. 6. Plan of the fortress Brieg (now Brzeg), part of the title sheet from the atlas “Kriegskarte von Schlesien”, volume 3. – SBB-PK: 2° Kart. N 15060‑1 – Photo by M. E. Adamska

As for the scope of possible conclusions on functional characteristics based on Wrede’s maps, I present it on the example of the town Oppeln (now Opole). Its plan shows that it has a regular layout, is located on the right bank of the Oder, surrounded by defensive walls. Regular blocks of development are mainly for housing. There are public buildings located in the area of the market square, three monasteries and the parish church on the outskirts of the town. Craft and industry premises are located along the river. The fork of the river forms an island, where a castle surrounded by ramparts and a moat is located. My research and the above initial conclusions were presented in 2023 at the ISUF Conference in Belgrade, where they were met with a great deal of interest.

Silesian towns exemplify repeatability on the one hand and individuality on the other. There are still many questions to be answered. There is a vast space for further research, both intra et extra muros. I plan to continue my study on the cultural landscape of Silesia in the 18th century on the basis of historical cartography. Kriegskarte von Schlesien definitely proved to be an invaluable source of information not only in the area of geography and history, but in the field of architecture and urban planning, too. The maps provide the unique opportunity of conducting multidirectional research on Silesia. I was able to come to this point of my study thanks to the generosity of the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin and its research grant awarded within the Grant Program of the Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz and also thanks to the kindness of all the people I met at the State Library at Berlin. I am sure that the collections of the Map Department can reveal many treasures awaiting their discovery.

Frau Prof. Monika Ewa Adamska, Technische Universität Opole, war im Rahmen des Stipendienprogramms der Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz im Jahr 2022 als Stipendiatin an der Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin. Forschungsprojekt: „Reconstructing the image of Silesian towns (intra et extra muros) in the 18th c. on the basis of ‚Krieges Carte von Schlesien‘ by Christian Friedrich von Wrede“

Public Domain

Public Domain![F[riedrich] E[duard] Bilz, Das Neue Naturheilverfahren: Lehr- und Nachschlagebuch der naturgemäßen Heilweise und Gesundheitspflege, Vol. I (Leipzig: Verlag von F.E. Bilz, 1898](https://blog.sbb.berlin/wp-content/uploads/IMG_2063a-180x180.png)

Public Domain

Public Domain CC BY-SA-NB

CC BY-SA-NB Foto von C. T. Jones

Foto von C. T. Jones

Foto: Sanjiao Tang

Foto: Sanjiao Tang Landesarchiv Berlin, einfaches Nutzungsrecht für SBB-Blog

Landesarchiv Berlin, einfaches Nutzungsrecht für SBB-Blog Lara Szymanowksy

Lara Szymanowksy Photo: Lukáš Kubík

Photo: Lukáš Kubík

Ihr Kommentar

An Diskussion beteiligen?Hinterlassen Sie uns einen Kommentar!