Social Reform in the Conservative 1850s : The Central-Verein in Preußen für das Wohl der Arbeitenden Klassen and the Kindergarten

Gastbeitrag von Nisrine Rahal, University of Toronto

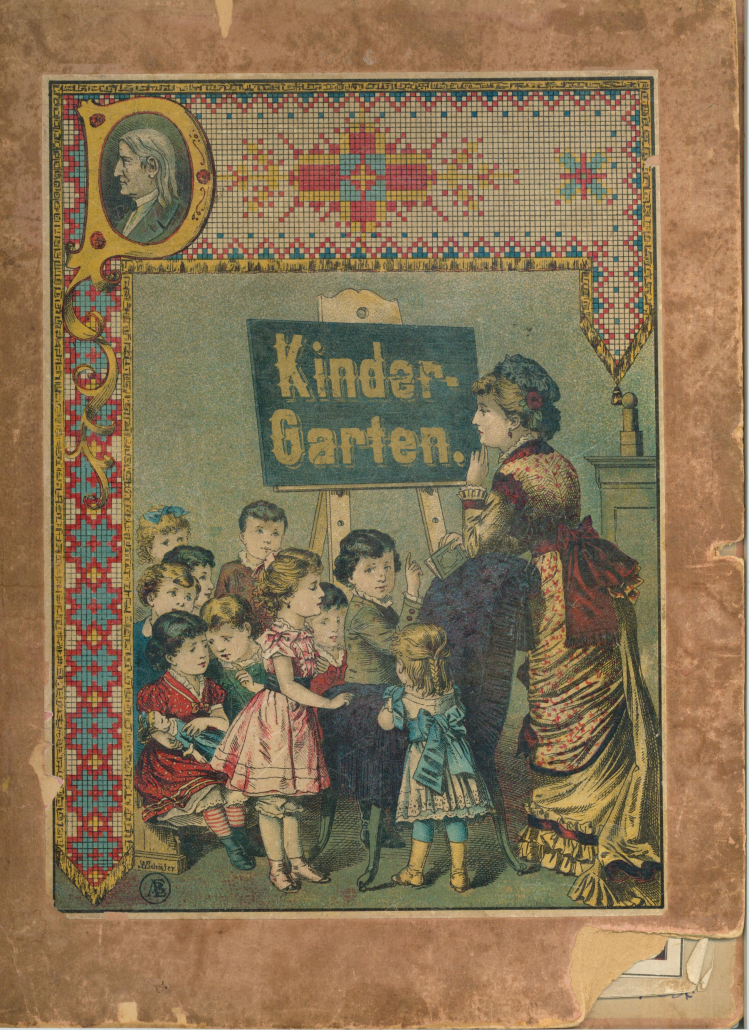

The kindergarten, founded in June 1840 by Friedrich Fröbel in Bad Blankenburg, was imagined as a “garden of children” from which a new humanity would evolve. Fröbel’s educational method focused on independent play motivated by toys and set activities. These activities, Fröbel believed, would allow children to learn their place in the world as well as develop their skills and individuality. The gardener, epitomized in the figure of the female kindergarten teacher, provided the maternal love and supervision that would assist the development of children.

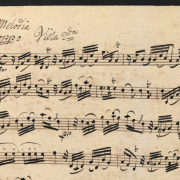

„Kindergarten“, Titelblatt (F639). – Source: Bildarchiv Friedrich-Fröbel-Museum Bad Blankenburg

The kindergarten, to activists, was a revolutionary institution. In Fröbelian newspapers, such as Friedrich Fröbel’s Wochenschrift. Ein Einigungsblatt für alle Freunde der Menschenbildung, activists wrote countless articles on the necessity of the kindergarten to construct a new society. Here, they found not only space to share pedagogical innovations, but also to discuss political and social change and protest. The kindergarten provided an alternative route to challenge the traditional authority of the state and the church. The democratic movement, workers’ associations, teachers’ unions, Christian dissenters, and women’s associations all promoted the kindergarten within their platforms as a route to change society.

For this reason, the kindergarten was targeted as a political and dangerous institution tied to the democratic movement. Berlin Polizeipräsident von Hinckeldey defined a circle of “democratic notables” who utilized the kindergarten to spread revolutionary ideas. Both Hinckeldey and Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm IV labeled the kindergarten a “nursery of destruction.” In August 1851, the kindergarten was banned as a “socialist” and “atheistic” institution.

So how does one study the kindergarten during the reactionary 1850s when a system of suppression was put in place against revolutionary activism? The Central-Verein in Preußen für das Wohl der Arbeitenden Klassen provides us with one answer to this question. The Central-Verein was founded in 1844 as a middle-class response to the social unrest among workers and weavers in Silesia. The organizers of the association sought to address the social question (meaning the question of poverty, social misery, and inequality) by means of cultivating community support and educating workers. Not only did they promote education as a vital element for social change, but they also helped spread public libraries, banks, and new forms of insurance. While many members of the association were under police surveillance and labeled dangerous revolutionaries, the Central-Verein continued its activism for social change during and after the conservative 1850s.

For the Central-Verein, early children’s education within pre-school institutions was part of a larger belief in uplifting the working class and promoting social reform. Members and pedagogues did not trust working class parents to provide young children with valuable early education in the household. Young children, they noted, were curious and learned through exploring. Appropriate educational institutions, such as the kindergarten, the Central-Verein believed, allowed to cultivate children’s natural curiosity, utilizing that as a pedagogical method for the proper mental, physical, and spiritual development of individuals.

Leopold Besser’s 1859 article “Ueber das Wohl der Arbeiterkinder in Klein-Kinder-Bewahr-Anstalten und Kindergärten” in the association’s newspaper, Zeitschrift des Central-Vereins in Preussen für das Wohl der arbeitenden Klassen, and Friedrich Ravoth’s April 19 1859 lecture, “Ueber den Geist der Fröbel’schen Kinderspiele und die Bedeutsamkeit der Kindergärten”, provide us with a window to examine how the kindergarten was mobilized within this liberal welfare movement. Both pieces not only seeked to challenge the state’s discrimination against the Fröbelian method, but also placed children’s education as a platform to discuss social reform.

In his article directed to middle-class reformers, Leopold Besser laid the groundwork for a re-examination of education in early childhood. He emphasized that one key issue plaguing the working class is poverty. Poverty prevented the mental and physical uplift of a vast majority of individuals. One area that would help stop the spread of this social disease would be public education. But how could this help those who were not old enough to go to school? These children, Besser wrote, would be at risk of being damaged in a key developmental phase of their lives. The kindergarten, and Fröbel’s method in particular, allowed for not only a more scientific approach to early child development, but also assisted parents through teaching them how to be better guardians.

Ravoth’s lecture illuminated a different setting of activism for the Central-Verein. In front of an audience of middle-class women and pedagogues, Ravoth discussed the developmental benefits of a system of play and the Fröbelian method. The period of childhood is connected with specific developmental goals. Toys and play, according to both Fröbel and Ravoth, allow children to develop mental and physical abilities to become perfect and productive individuals in society. Toys and carefully crafted activities wake children’s natural abilities largely to benefit all of society, not just the individual.

For both Besser and Ravoth, Fröbel’s pedagogical method was not simply educational, but also maintained a social hygienist value. Not only did the kindergarten battle poverty, but it also provided for the proper growth of human society. As Ravoth stated to his audience, “medicine…takes a special interest in all social aspirations and, according to one of its most important teachers and representatives (Virchow), it feels called upon to raise a crucial and important voice wherever it comes to social reforms.” (Ravoth, p. 2) Both Besser and Ravoth highlighted a clear change in kindergarten activism. Not only was there an attempt to bring the kindergarten back into social welfare activism, but also, as a new approach, the language of medicine was emphasized. The social hygienist approach to children’s play informed both discussions.

Both Besser and Ravoth demonstrated how liberal reform movements, such as the Central-Verein, were able to move beyond state-suppression. Here, the issue of social reform focused on educational uplift. Middle class women were idealized as key agents for this social change, however the notions of emancipation and revolution were left out. While by no means endorsed by the state, the Central-Verein (still suspect in the eyes of conservatives as it was) nonetheless continued to mobilize an ideal of society that challenged traditional authority. It exemplifies a continuation of activism for social change from the revolutionary 1840s through to the 1880s.

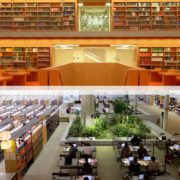

The Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin allowed me as a historian of the kindergarten movement to follow the ways activism continued and was transformed during the conservative 1850s. The Central-Verein illuminates a continuation of revolutionary social reform that did not simply disappear. Rather there was a change in language and approach.

Our two sources provide us with a preview of a whole larger discussion that included petitions to governments, responses to state suppression through published pamphlets, and continuous meetings of social reformist teachers.

Frau Nisrine Rahal, University of Toronto, war im Rahmen des Stipendienprogramms der Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz im Jahr 2018 als Stipendiatin an der Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin. Forschungsprojekt: „A Garden of Children and the Education of Citizens: The German Kindergarten Movement from 1837 – 1880“

Public Domain

Public Domain

Historial de la Grande Guerre - Musée de Péronne (Somme)

Historial de la Grande Guerre - Musée de Péronne (Somme)

© Alinari Archives / Universal Images Group / For Education Use Only

© Alinari Archives / Universal Images Group / For Education Use Only

Public Domain Mark 1.0

Public Domain Mark 1.0

Ihr Kommentar

An Diskussion beteiligen?Hinterlassen Sie uns einen Kommentar!