Military Drugs and Medical Texts: The Berlin Chinese Medical Manuscripts and Patterns of Consumption in the Mid to Late Qing

Gastbeitrag von Forrest Cale McSweeney

In the Qing Dynasty (1644–1912), military medicine, and particularly military drugs, were an aspect of the income of soldiers. In a complex system of local procurement, the Qing government steered both simple ingredients and physicians themselves to the privileged Manchu warrior elite in the Eight Banners often stationed in the far West, and likewise to regular soldiers in the Green Standard Armies. After the 1780s this procurement process was governed by the War Expenditures Regulations junxuzeli 軍需則例 (the Qing created specialized regulations called zeli 則例 for a variety of administrative domains). However, apart from this, the Qing emperors dispatched chengyao 成藥, or pre-prepared formulas, directly to soldiers throughout the empire through the honorary conferral system which had been a regular feature of government in imperial governments since the Tang Period (618–907).

Such pre-prepared formulas were the products of China’s new and enormous bulk of pharmaceutical industry. By the 18th century these firms had begun to aggressively publish and market their drugs directly to consumers, particularly through the circulation of their catalogues (yaomu 藥目). The most successful pharmacy and the one closest to the Qing government was the Tongrentang 同仁堂. Of the 95 formulas confirmed to have been distributed to Qing soldiers from the 18th through the 19th century, 47 appeared on the Tongrentang’s catalogue. This amounted to a virtual subsidy for the metropolitan pharmaceutical industry in the Qing.

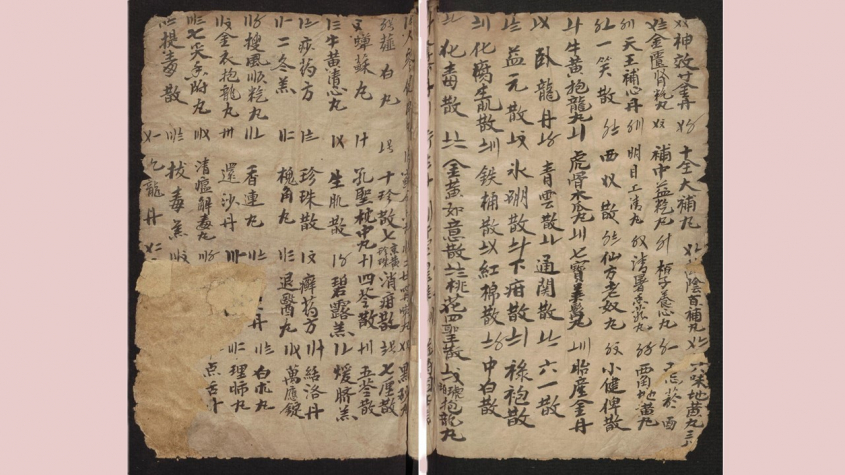

This cuts against our typical understanding of medicine in the Qing, which according to most scholars became far less attached to the state both materially and discursively throughout late imperial China from the mid-Ming (1368–1644). But was the state merely an indirect player in this new scene? Is it possible that the Qing state’s drug distribution efforts actually enhanced the profile of some drugs over others, even over that of the efforts of the pharmaceutical industry? Moreover, what can the Berlin Library’s Unschuld collection, the “Chinese Medical Manuscripts”, add to this discussion? These roughly thousand manuscripts contain a wide variety of individually copied medical texts primarily intended for private or use within a closed system of associates and circulated only incidentally. They range from copies of esteemed medical classics to large numbers of recipe collections reflecting the individual inclinations of physicians often operating beneath the level of mainstream medical literature.

It has long been a suspicion by scholars that in the late imperial period, the classical medical tradition operated more often than not as a legitimizing veneer over a much more obscure level of practical discourse which, in practice, viewed classical medical systems established in the Han Period (202 BCE–220 CE) expediently. With the added variable of known military drugs, we can further develop and clarify this hypothesis. Was Chinese practical medical discourse organized in any systematic way? Were there obvious patterns of consumption and practice which point to the influence of institutions, including the state? We can start to answer these questions by first trying to create a clear indicator of the Qing state’s capacity to modify medical discourse, starting at the published literate level. With the use of digital humanities tools and including many open-source databases, it is possible to see in clear terms the profile specific formulas had in the published medical records. The big pharmacies like the Tongrentang did not limit themselves to formulas they themselves allegedly invented, but rather they also co-opted previously existing formulas from a wide variety of origins, sometimes medieval or even ancient. Comparing the incidence of military formulas vs. Tongrentang (TRT) formulas across time, reaching back to the Song‑Jin‑Yuan Period (SJY, 960–1368), all relative to a control group as a baseline, can begin to illustrate the relative power of the state to enhance the profile of a specific formula.

Nearly all formulas distributed by the Qing or sold by the TRT which ultimately came from the medieval period begin at a consistently low textual incidence of 1‑2 texts per formula during the SJY and remain flat until the mid-Ming, when printing in all literary fields exploded. TRT formulas show a tendency to increase over time from the Ming (3.2 texts per formula) to the end of the Qing (10.1) – a factor of 3.2, noticeably higher than control at 2.7. The Qing government, when distributing medieval-era formulas, tended to select from high profile formulas, which increase from 7.45 in the early Ming to 35.25 by the late Qing texts – a factor of 4.3. But the Qing government often distributed TRT formulas to Qing soldiers. Such hybrid formulas skyrocketed in Qing texts, increasing by a factor of 7.85. It seems from this that Qing military distribution could have acted as a multiplier on TRT formulas, but this can only be seen most clearly when comparing these against military formulas totally unaffiliated with the TRT, where the factor actually increases – to 8.3. The Qing government was just as strong a multiplier as the most famous pharmacy in China, if not stronger.

The Unschuld manuscripts provide a glimpse into the efforts by physicians by the late Qing and early republican periods to determine the composition of such popular formulas, as the great pharmacies tended only to publish their applications, not their compositions. Formulas which came from the Qing’s Imperial Medical Academy Taiyiyuan 太醫院 were only recorded semi-officially in the private intra-government diaries and formularies of the Taiyiyuan and Imperial Pharmacy Yuyaofang 御藥房 physicians, which remained unpublished until modern times.

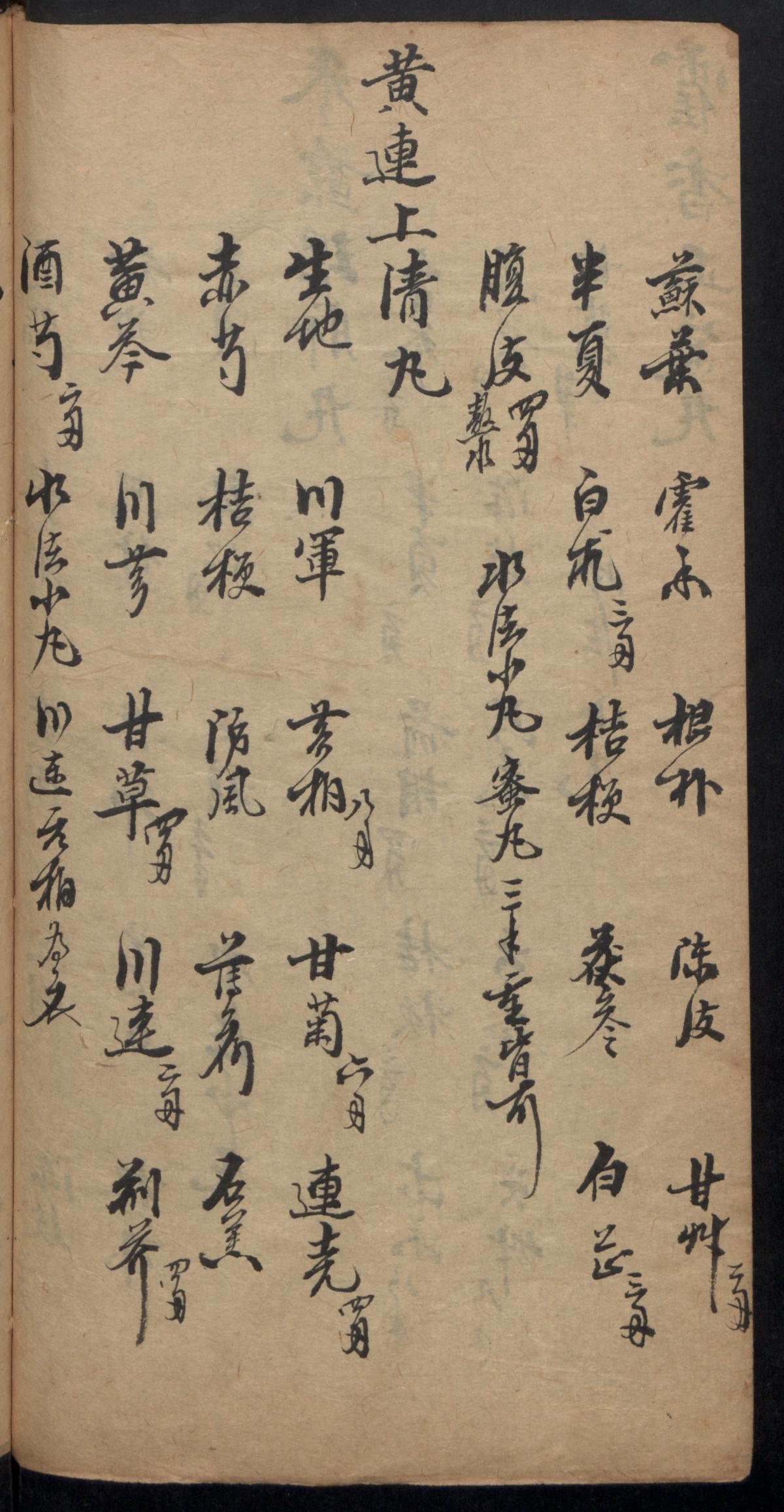

One group of military formulas stands out in terms of their relevance to the collection. They are those formulas which have an extremely limited or even negligible presence in the larger historical-literary record, yet were nonetheless distributed to Qing soldiers. It is in the Unschuld collection where some of the only historical records exist of what precisely these formulas (in total 14) consisted of and what they were used for by physicians. If Qing military distribution was a significant multiplier to a formula’s profile, then why did these formulas remain relatively obscure and appear only in practical literature? Analyzing the Unschuld manuscripts for patterns against the assumption that military distribution affected the formulas’ profiles offers clues. Despite all having virtually no presence in mainstream texts, medical or otherwise, some formulas can still be incredibly common across the practical domain. The drug Huanglianshangqingwan 黃連上清丸 “Pills with Rhizoma Coptidis to Clear the Upper Body” is an example of this, being invisible in medical and historical literature yet appearing in 52 separate manuscripts. At the other extreme is “Depression-Overcoming Harmony-Preserving Pill” Yuejubaohewan 越菊保和丸, which appears in only two.

Formulas were often obscure in literature but popular in manuscripts: cf. entry Huanglianshangqingwan 黃連上清丸 “Pills with Rhizoma Coptidis to Clear the Upper Body” from Wansangaodan 丸散膏丹 “Pills Powders Plasters and Elixirs”, p. 54. – SBB‑PK: Slg. Unschuld 8002 (Retrieved from http://resolver.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/SBB0000601F00000054)

Despite such range, most of the formulas exhibit a profound degree of standardization throughout the collection in spite of the fact that the published record could not have provided a conduit of communication between the authors of the manuscripts. The fact that many such formulas appear on the TRT catalogue would in theory account for this. Huanglianshangqingwan is regularly appended with variants of the catalogue’s claim that it “treats overabundance/fullness of heat/fire in the triple burner” 治三焦實火. Fenqingwulinwan 分清五淋丸 “Clear-Turbid Five Stranguaries Pill” is a counterexample. Being absent from the TRT catalogue, practitioners would have had to find its application of “treating heat evil of the bladder and a swollen and painful penis” elsewhere, yet not only is its composition very consistent across documents, but this application does even repeat verbatim. Where did this formula come from, if not from medical literature? The most immediate possibility is: directly from the Qing court. Fenqingwulinwan appears in at least two modern reconstructed private intra-government diaries or formularies, where their applications to bladder diseases were the same, but their compositions were inconsistent. The ingredients from the Unschuld documents, though, draw from the common ingredients from the government formularies. There is a possibility that composition diffused from the imperial court.

A concordance between imperial court use and the practical literature of the Unschuld manuscripts would not be unexpected. Using Chen Keji’s 陈可冀 systematic cataloguing of court medical cases in the Qing, one can find many obscure military formulas in use both at court in the Qing and in the manuscripts, such as Wujisanwan 五積散丸 (for cold affliction in the stomach), Jinyiqushuwan 金衣祛暑丸 (dispelling summerheat and unseasonal qi), Jiuqiniantongwan 九氣拈痛丸 (heart problems). The Qing court regularly used highly obscure formulas it shared with its soldiers, completely bypassing its own orthodox medical compilation, the “Golden Mirror of Medical Orthodoxy” 醫宗金鑒. Fully three-quarters of Qing military drugs do not appear in it, and half were absent from the Golden Mirror and yet were still used at court. The question remains, was it really the big pharmacies which were accounting for this concordance?

Only one obscure military formula is in the best position to approach this question. Xijiaoshangqingwan 犀角上清丸 “Rhinoceros Horn Upper-Body-Clearing Pill” did not appear on the TRT catalogue, was used at court (to treat heat related diseases), and also appears among the Unschuld manuscripts. The only records of its composition are four internal formularies, where the composition profile is inconsistent with only a few overlapping ingredients. Nonetheless, when appearing in the Unschuld documents its applications always include the treatment of heat, and virtually all of its ingredients named in the Unschuld collection can be found in at least one of the surviving internal formularies. The implication is a tempting hypothesis: The Qing imperial court dictated to the Qing and later practical medical domain, by bypassing medical literature, through subsidizing the pharmaceutical industry and dispersing specific formulas through military distribution. It was the state, not the pharmacies, which enhanced drug profiles. More research is needed of course.

A counterpoint to this hypothesis would be the interesting case of Pinganwan 平安丸 “Peace and Security Pill”, certainly the most enigmatic formula of the early modern period. A simple search through the catalogues of the First Historical Archives of China will reveal that this formula was nearly omnipresent in the Qing official sector from approximately the Yongzheng Period (1722–1735), being distributed to civil officials, generals, bannermen, regular soldiers. No other medical formula appears more commonly in military distribution records or even in civil or court records.

Pinganwan appears on the TRT catalogue as a formula for treating a number of ailments, including “the nine kinds of heart pain” jiuzhongxintong 九種心痛 and a variety of gastrointestinal pains and disorders. However, because of its ubiquity in Qing government, a variety of archival sources reveal it had a wide variety of incompatible applications. It was sent to the Manchu general Fukanggan (1644–1766) in the Miao campaigns of the 1790s to help cure summerheat stroke. In Nepal in 1793, a thousand soldiers received the drug to combat miasmas. In 1729, an official received it for exposure to cold pathogen – probably a febrile disease. In 1722 Emperor Yongzheng himself cut straight to the point and just called it a wonder drug. This gets even more complicated in a case from 1759, when in Xinjiang, a memorial from the Manchu general Zhao Hui thanked the emperor for a conferral containing pinganwan and xianglianwan, both explicitly labelled “such medicines which cure blade and firearm wounds”. I can find only very limited evidence within any state or private sources suggesting pinganwan was used to treat wounds, especially ones identified so specifically. The only relatively well-known text pinganwan appears in is Ma Wenzhi’s 1892 collection on external medicine, which omits its application.

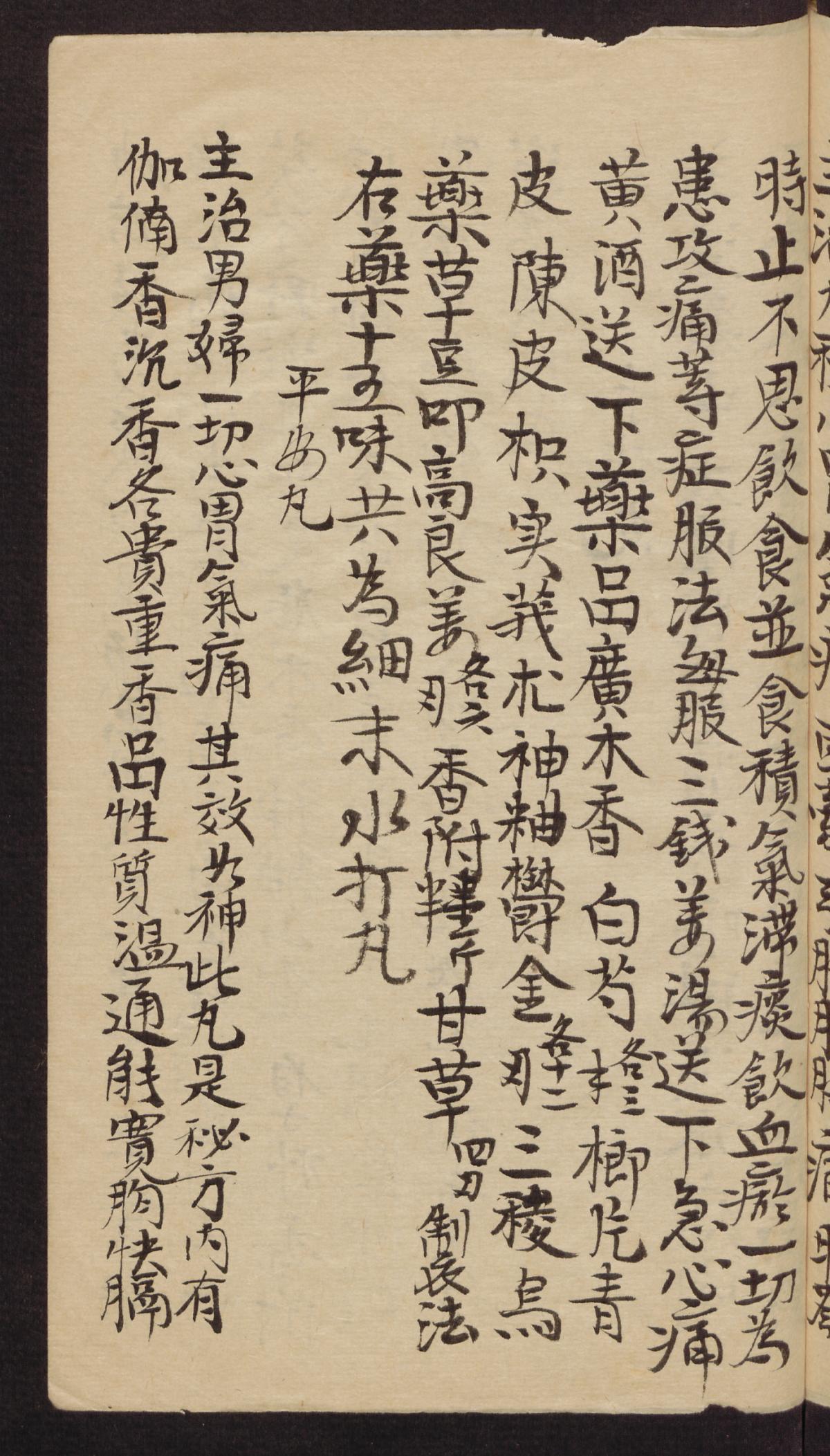

Widely circulated Pinganwan was all but unknown in wider medicine: cf. entry Pinganwan 平安丸 “Peace and Security Pill”, p. 109. – SBB-PK: Slg. Unschuld 8222 (Retrieved from http://resolver.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/SBB0000608E00000109)

The mystery only compounds with the Unschuld collection, which has only a single entry of the drug, explicitly labeling it a “secret formula” mifang 秘方 and only very cursorily referencing aspects of its TRT description while giving only scant details of its composition. This is a departure from the normal experience when analyzing Qing military formulas in the Unschuld collection, which normally exhibit a reliable degree of standardization. However, in this case it is perhaps understandable as even Chen Keji could find no fewer than four separate recipes prevailing in the Qing period, each with highly inconsistent ingredients. The formula being in some sense secret cannot be an explanation for its inability to break out into larger discourse, as nothing could have been less of a secret in Qing government. At this point I speculate that the explanation lies at the top: Pinganwan was essentially a discretionary panacea, possibly influenced by the whims of imperial medical dilettantism, particularly of the emperor Yongzheng, who informally prescribed the drug to dozens of officials at a whim. Its resulting lack of standardization hampered any ability for it to circulate in the informally formatted system that was Qing practical medical discourse. This could explain how such a drug with such wide support from the state could have such a marginal impact outside of the state sector while allowing for the very real active correspondence between Qing medicine in government and in common medical practice. In the Qing, medical knowledge descended from state sectors via the military, but in many ways the halls of court, the offices of bureaucracy, and the garrisons of soldiers could each be their own medical worlds.

Herr Forrest Cale McSweeney, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, war im Rahmen des Stipendienprogramms der Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz im Jahr 2024 als Stipendiat an der Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin. Forschungsprojekt: „Military Drugs From Soldiers to Physicians“

Vortrag im Rahmen von CrossAsia Talks am 20. 6. 2024

Aufzeichnung des Vortrags

Public Domain

Public Domain

Public Domain

Public Domain Foto: Sanjiao Tang

Foto: Sanjiao Tang Public Domain

Public Domain

Public Domain 1.0

Public Domain 1.0

Ihr Kommentar

An Diskussion beteiligen?Hinterlassen Sie uns einen Kommentar!