Reading the Book of the Body: Flap Anatomies and the Naturheilkunde Movement in Germany, ca. 1880–1920

Gastbeitrag von Jessica M. Dandona

The late nineteenth century witnessed a revolution in book printing and distribution, the effects of which were felt around the world as new ideas, images, and information rapidly traversed international borders and reached new audiences. This global trade had a profound impact on the production of human knowledge – and on how we conceptualize the body, medicine, and health. My research focuses on late nineteenth-century “flap anatomies” — printed atlases of human anatomy that offered readers the opportunity to engage in a virtual dissection as they folded back layered depictions of the body and its structures. While the color illustrations for these movable books often originated in Germany, versions of these paper manikins also proliferated in France, Britain, and the United States, as well as further afield. Designed to appeal to both professional and popular readers, flap anatomies gave visual form to a newly medicalized understanding of the body, one based upon anatomical science. Through their use of movable flaps, they also put touch and the knowledge thus gained directly into the hands of readers, challenging the authority of conventional medicine through embodied forms of learning and exploration.

In August 2025, I spent a month at the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, working closely with printed flap anatomies, thanks to a research grant from the Stiftung Preussischer Kulturbesitz. I had two goals: to identify the full range and extent of the use of flap anatomies in German medical treatises published between 1880 and 1920 and to trace the evolution and movement of these printed illustrations on a national and international scale.

While vividly colorful, multilayered flap anatomies appear frequently in English-language publications such as Dr. Minder’s Anatomical Manikin of the Human Body (ca. 1899) and even in life-size models such as the Pilz Anatomical Manikin (ca. 1900), the frequent mention “Printed in Bavaria” led me to wonder how many such works originated in Germany. In this period, Germany was the undisputed capital of chromolithographic publishing, exporting vast numbers of prints to Britain, the United States, and other countries in the form of postcards, die-cut scraps, and even cigar-box labels. It seemed reasonable to conclude that 19th-century flap anatomies may have likewise owed their origins to German printers and publishers.

It is undeniable that the longer history of flap anatomies is closely associated with German-speaking regions. Perhaps the earliest anatomical work published with attached, movable flaps is Heinrich Vogtherr’s single-sheet print Anothomia, oder abconterfettung eines Weybs leyb/wie er innwendig gestaltet ist, published in Strasbourg in 1538, which depicts a female figure whose torso opens to reveal her internal organs. Vogtherr went on to produce a second sheet depicting the male body in 1539, and both versions appeared frequently in pirated works for over a century. The illustrious anatomist Andreas Vesalius employed a similar format for the student version of his revolutionary publication De humani corporis fabrica, entitled the Epitome (Basel, 1543), but required readers to assemble their own paper manikins from the images provided. The most elaborate flap anatomy to appear in book form prior to the 19th century is Johann Remmelin’s Catoptrum microcosmicum, first published in Augsburg in 1614. Remmelin’s work combines anatomical study with references to religious and alchemical traditions, creating a richly metaphorical representation of corporeal form.

While interactive exploration of the body was a central component of these early works, none display the complexity, realism, or vibrant colors characteristic of 19th-century examples, which prompted me to ask: how do fin-de-siècle flap anatomies convey a specifically modern conception of the body, one premised upon both new technologies and new approaches to healing?

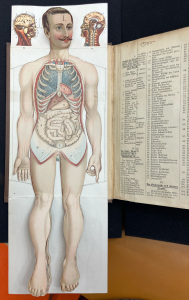

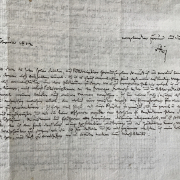

Fig. 1. F[riedrich] E[duard] Bilz, Das Neue Naturheilverfahren: Lehr- und Nachschlagebuch der naturgemäßen Heilweise und Gesundheitspflege, Vol. I (Leipzig: Verlag von F.E. Bilz, 1898).

During my stay in Berlin, I quickly discovered that the most influential and widely circulated of these flap anatomies is likely Friedrich Bilz’s Das Neue Naturheilverfahren, or The New Natural Healing Method, first published in Germany in 1888 and eventually translated into 13 languages (Fig. 1). The founder of a sanatorium near Dresden, Bilz marketed his treatise door to door, via correspondence, and at public health lectures. By the late 1930s, nearly 11 million copies had been sold in Germany alone, and new editions of the work would appear as late as the 1950s.

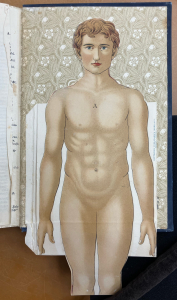

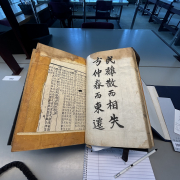

Fig. 2. Anna Fischer-Dückelmann, Mann und Weib: Gegenüberstellung des männlichen und weiblichen Körpers in anatomisch zerlegbaren Modellen: Album zu: Die Frau als Haus-Ärztin (Stuttgart: Süddeutsches Verlags-Institut, [1910?]).

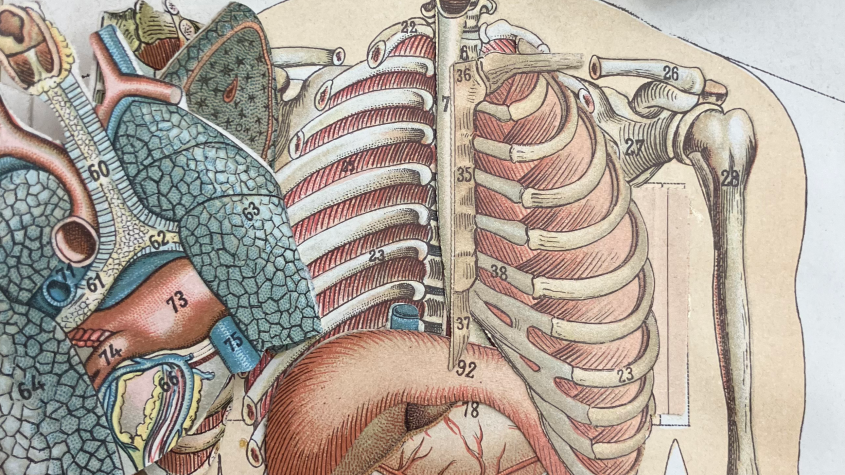

Fig. 3. Moritz Platen, Die Neue Heilmethode: Lehrbuch der naturgemäßen Lebensweise, der Gesundheitspflege und der arzneilosen Heilweise; Ein Haus- und Familienschatz für Gesunde und Kranke; Mit 432 in den Text gedruckten Abbildungen, 24 Chromotafeln, dem Bildnisse des Verfassers und 7 zerlegbaren anatomischen Modellen, Vol. I (Leipzig: Dt. Reichsverl., R. Krause, 1901).

Moritz Platen, Bilz’s former secretary, would likewise publish a popular treatise with broad appeal, Die Neue Heilmethode (1894). Focused on ‘natural healing’, Platen’s work includes flap anatomies of the male and female body, regularly updated to reflect changing standards of ideal physical form and beauty (Fig. 3). While the works of Bilz, Fischer-Dückelmann, and Platen appear in numerous editions stretching over a half-century and beyond, their influence extended far beyond the original publication: my research uncovered numerous examples of lesser-known works that employ remarkably similar movable figures. While some instances no doubt reflect publishers’ tendency to reuse costly illustrations across multiple publications, the appearance of near-identical figures in works printed in many different countries suggests that the sale of flap anatomies constituted a flourishing trade in its own right.

Given the ubiquity of flap anatomies in publications dedicated to promoting popular understanding of the body and its structures, what can such works tell us about the world of 19th– and early 20th-century medicine? My recent paper, “A New Book of the Body: Friedrich Bilz’s Illustrated Guide to Health,” presented at the conference Object Stories in Health and Medicine, 1700–1900, builds upon my research in Berlin. I consider how the use of flap anatomies may have marked popular medical treatises as both ‘modern’ and ‘scientific’, while also valorizing notions of therapeutic touch and ‘natural healing’ understood as alternatives to mainstream medicine. I will expand on these ideas in an upcoming contribution to The Routledge Companion to Book Studies (forthcoming 2027). My investigation of the origins of 19th-century flap anatomies would have been unthinkable without the kind assistance of the librarians at the Staatsbibliothek, who facilitated my access to these fragile materials and permitted me to experience them as they were intended – through both curious sight and careful touch.

Prof. Jessica M. Dandona, Minneapolis College of Art and Design, war im Rahmen des Stipendienprogramms der Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz im Jahr 2025 als Stipendiatin an der Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin. Forschungsprojekt: „The Book of the Body: The 19th-Century Flap Anatomy as Body/Text„

Wissenswerkstatt SBB-PK CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

Wissenswerkstatt SBB-PK CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 Landesarchiv Berlin, einfaches Nutzungsrecht für SBB-Blog

Landesarchiv Berlin, einfaches Nutzungsrecht für SBB-Blog

CC-BY-NC-SA

CC-BY-NC-SA Photo: Lukáš Kubík

Photo: Lukáš Kubík

Ihr Kommentar

An Diskussion beteiligen?Hinterlassen Sie uns einen Kommentar!