Fighting the Colonial Enemy: The Challenges to the German way of War 1904–1918

Gastbeitrag von Leslie Newsom

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, conflict between the native populations of Africa and military forces of the European imperial powers seriously challenged the established idea of ‘White’ European military and physical superiority over the ‘Black’ populations of Africa. The perceived racial supremacy of the English was undermined by the victories of the Zulu Kingdom led by Cetshwayo in 1879. Most notable of these victories was the Battle of Isandlwana in which a force of approximately twenty thousand Zulus defeated a British invading force of eighteen hundred. This setback for the British led those propagating the racialised image of Africans to reinvent the stereotype into one that portrayed the ‘noble savage’, a warrior whose physique was to be emulated by the British soldier, but one who lacked the technological and cultural advantages of the typical European soldier.

The German overseas empire found its own ideas of racial supremacy challenged a quarter of a century later when the Herero and Nama people in German Southwest Africa rebelled against German colonial rule. The German military response to the rebellion led to a series of wars between 1904 and 1907 and resulted in the genocide of the Herero population. The response from those who wished to maintain the idea of German racial and military superiority had to address this, as did the British. However, the German response took a different form, instead of focusing on the physical attributes of the enemy warriors they used the unfamiliar terrain and ‘uncivilised’ tactics of the Herero to explain military defeat.

In both imperial metropolises, military defeats and difficulties in re-establishing control of the rebellious colonies had to be addressed in the wider population – a reflection of the need to maintain the myth of racial supremacy and the ‘moral’ burden to colonise and control ‘lesser’ peoples for their own good. This attempt to influence populations in Britain and Germany can be witnessed in many cultural artifacts, including those from childhood.

An adult, when purchasing a book, game, or toy for a child selects the item with the bias of their own world views and a wish to influence and inform the child. Because of this, through looking at childhood and the items which populate its space historians can view the attitudes, anxieties, and trends in society. The dissemination of ideas present in British and German societies reached the children’s nurseries, playrooms, and schools. Books and magazines published articles and stories that propagated the racist ideas of the imperialists and the military – deliberately invading the ‘safe’ spaces of childhood.

Evidence of this invasion of children’s lives by imperialists and the military to propagate racialised images of Germany’s colonial enemies are present in collections of children’s literature, such as that found in the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin. For example, the choice of articles chosen by the editors of Der gute Kamerad (Stuttgart) and the language used in them demonstrate the way in which material for children supported the ideas and narratives of the adult world. The agenda of the publication’s editors and writers is clear and in line with the wishes of the military and empire builders.

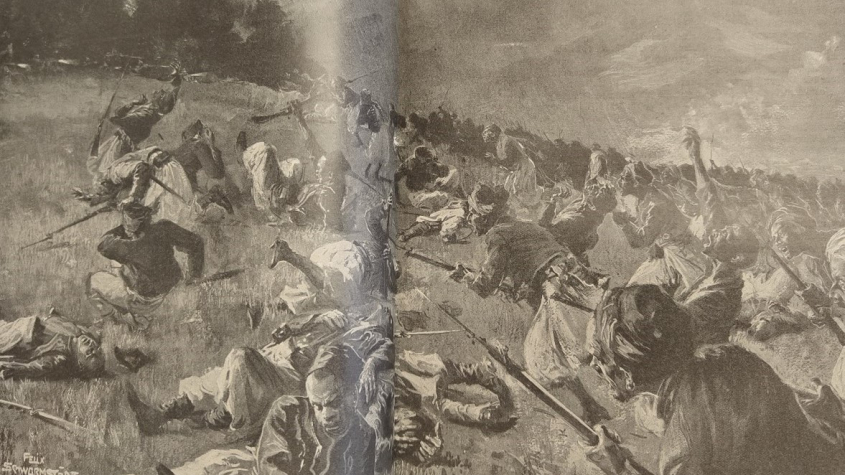

The 1908 issue of the annual Der gute Kamerad expresses the writer’s opinion that the difficulties that the German army was encountering in German Southwest Africa were not due to any superior physical prowess of the ‘savage’ Herero ‘rebels’, but caused by the unconventional (and in some way underhand) way in which the enemy waged war. The ‘rebellious Herero’, the article claims, fought as a ‘crowd’ akin to ‘hunters in the wild’ – a form of fighting that was ‘fundamentally different’ from what the German army was trained for. The writer of the article also pointed out that the biggest challenge the German soldiers were facing was not any martial prowess on the part of the Herero soldiers but the ‘unfavourable and alien environment’ of southern Africa.

This image of the Herero and the conditions experienced in German Southwest Africa were also replicated in toys designed and distributed so that children could recreate the conflict on their playroom floors. Parents and children could purchase sets of ‘flat’ toy soldiers, printed on card and intended to be cut out and mounted on bases. In one example held by the Deutsche Marinemuseum in Wilhelmshaven, the Herero are depicted as savages dressed in grass skirts and armed with nothing more than spears and shields – far from the reality of proficient soldiers in European style dress and armed with rifles. The German troops are all depicted in full uniforms, armed with rifles, and victorious – none of the figures that represent wounded, or dead, are in German uniforms. The ‘set’ also includes some pieces of terrain to represent the battlefield. This is presented as a rough, cactus populated region, almost alien to the European soldiers (the images of flora are incorrect for the region, this misrepresentation of the reality is common in European images of colonies).

Unsere braven Landstürmer by Adolf Ott, cover. – SBB – PK: Krieg 1914‑18683

(Quelle: http://resolver.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/SBB0000AD6300000001)

This German military attitude towards the use of non-European forms of warfare and the believe that in some way African fighting men and their different tactical approaches to conflict were underhand or ‘unfair’ continued into the conflict of 1914–18. Again, children’s literature can provide clear examples of what the prevailing attitude was towards the use of colonial troops in the First World War. The author, Adolf Ott, explained the use of African troops by Britain and France and the impact on the German soldier to his young readers in Unsere braven Landstürmer (Mein Vaterland, Bd. 40; 1918). The British and the French, he argued, used ‘white and coloured auxiliary people’ to ‘keep safe the blood of their own countrymen’ – implying that the German soldiers would, and could not hide from danger and let non-Germans defend Germany. Again, the alien nature of the African troops is used as a reason for defeat. In the eyes of authors such as Ott, it is understandable that German men would fear the ‘wild’ and ‘more or less cannibal’ nature of the Senegalese and Congolese regiments that stormed the German lines.

Despite the rhetoric accusing Britain of using African troops in Europe, the British Army was equally reluctant to employ black Africans in Europe, as the possibility of Africans killing white Europeans on European soil would have seriously undermined racist views of superiority based on skin colour. Britain did employ African and Caribbean units in support roles in Europe, but never on the front lines – a position reserved for British, Dominion, and Indian troops.

It is without doubt that racialised images of the ‘inferior’ African were challenged by the experience of European military units in colonial conflicts. In response to this, imperialists and the military in Britain and Germany attempted to rationalise the defeats of their ‘superior’ soldiery by creating an image of a physically powerful but savage warrior that fought in a way alien to the ‘civilised’ European citizen soldier. These anxieties about the undermining of the racial hierarchy continued into the twentieth century and shaped attitudes to the use of colonial units on European soil – both Britain and Germany fearing the consequences of Black African soldiers killing White Europeans on European soil.

Herr Leslie Newsom, University College London, war im Rahmen des Stipendienprogramms der Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz im Jahr 2023 als Stipendiat an der Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin. Forschungsprojekt: „British and German Children’s Informative Introduction to Imperialism and Militarism Through Education and Play, 1880–1918″

Seminar Disillusionment, Death, and Duty in German Childhoods, 1916-1918

University of London, Institute of Historical Research: Mittwoch, 13. November 2024, 18:30 MEZ

Option der Teilnahme online: https://www.history.ac.uk/seminars/modern-german-history

Public Domain

Public Domain![F[riedrich] E[duard] Bilz, Das Neue Naturheilverfahren: Lehr- und Nachschlagebuch der naturgemäßen Heilweise und Gesundheitspflege, Vol. I (Leipzig: Verlag von F.E. Bilz, 1898](https://blog.sbb.berlin/wp-content/uploads/IMG_2063a-180x180.png)

Public Domain

Public Domain CC-BY-NC-SA

CC-BY-NC-SA

CC-BY-NC-SA 3.0

CC-BY-NC-SA 3.0

https://pixabay.com/de/vectors/frau-megaphon-schrei-apropos-4370509/

https://pixabay.com/de/vectors/frau-megaphon-schrei-apropos-4370509/

Ihr Kommentar

An Diskussion beteiligen?Hinterlassen Sie uns einen Kommentar!