Jacques Noir’s Facing Berlin: Discovering the Legacy of a Refugee Poet

Gastbeitrag von Katya Knyazeva

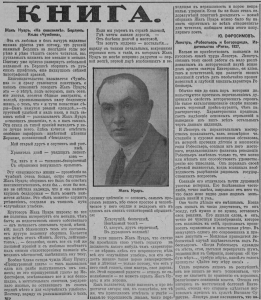

In summer 1922, the Russian poet Iakov Oksner moved to Berlin. The Russian population of the city, made up mostly from refugees from the 1917 Bolshevik revolution and the Civil War, was in the hundreds of thousands. The intellectual life was vigorous; newspaper and book publishing thrived. In autumn 1923, however, pressured by the rising cost of living, the Russians began to leave Berlin in large numbers and resettle in Paris, Prague and other places. Only a minority of émigrés stayed in Berlin; Oksner was among them. From 1924 to 1931, he published satirical and nostalgic verses in Riga-based newspapers Segodnia and Vechernee Vremia, Berlin’s Vremia and Rul, and others – altogether more than 400 of his original poems appeared in fifteen Russian-language periodicals aimed at the émigré audience. His poems described, with wit and compassion, the daily preoccupations of the exiled Russians, global and local political events, and the peculiarities of the German culture. Some of these poems found their way into Oksner’s five poetry collections, produced in 1924–1927 by Berlin-based Russian publishers; he also wrote seven illustrated children’s books.

Apart from his literary work, Oksner’s fifteen years in Berlin are shrouded in mystery, as were his subsequent five years in Bucharest and Chisinau, leading to his violent death in 1941. A talented but nearly forgotten writer whose life ended in tragedy, he is now reemerging thanks to the preservation of five of his poetry books at the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin. Additionally, the digitization of archival periodicals by the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin and the Latvian National Digital Library made it possible to locate his poems in the newspapers Rul (Berlin) and Segodnia (Riga). The literary oeuvre of Iakov Oksner (who signed his work “Jacques Noir”) is virtually the only record of his circumstances and movements, as well as an invaluable window into the life of the Russian diaspora in Berlin.

Iakov Vigdorovich Oksner was born in 1884 in a middle-class Jewish family in Făleşti, in Imperial Russia’s Pale of Settlement (today’s Moldova). The Jews were frequently expelled from Făleşti, so Oksner ended up growing up in the neighboring Bălţi and Chisinau, more secure Jewish-majority towns. In 1907, he married Sofia Moiseevna Sigal, from an Odessa merchant family. They settled in Odessa and later moved to Chisinau, where Oksner pursued a career in bank administration. Around 1905, his satirical verses started to appear in regional periodicals, such as Bessarabskaia Zhizn, Satirikon, Ogonki, Epokha and Novoe Slovo; at Satirikon he became a member of the editing board, alongside the magazine’s founder, the writer Arkadij Averchenko.

Author’s name. – From: Litsom k Berlinu, cover. -SBB: 434380

“Jacques Noir” – Iakov Oksner’s nom de plume – was apparently borrowed from a 1909 Russian comedy play titled Zhak Nuar i Anri Zaverni, ili Propavshij dokument [Jacques Noir and Henri Zaverni, or a Stolen Document], which parodied French theatre. In the play, Jacques Noir is a cunning black African criminal, in a cloak and a wide-brimmed hat, who assumes a fake identity to deceive simple-minded townsfolk. This character is far removed from the real Iakov Oksner, whom Vladimir Nabokov described in his 1933 novel Dar [The Gift] as “a frail little man with a kindly wit and a quiet, hoarse voice” [Nabokov, The Gift, 1991 translation]. The journalist Zinovij Arbatov confirms that Oksner was short and slightly hunched, “with a vague sarcastic smile on a thoughtful face”. He also admits that “in spite of these unattractive looks, Oksner managed to find a loyal German woman who accompanied him for years, ran his household, took care of his laundry, darned his socks and always checked that his trousers were perfectly creased before he went out” [“Nollendorfplatzcafé”, Grani, No. 41, 1959, 117].

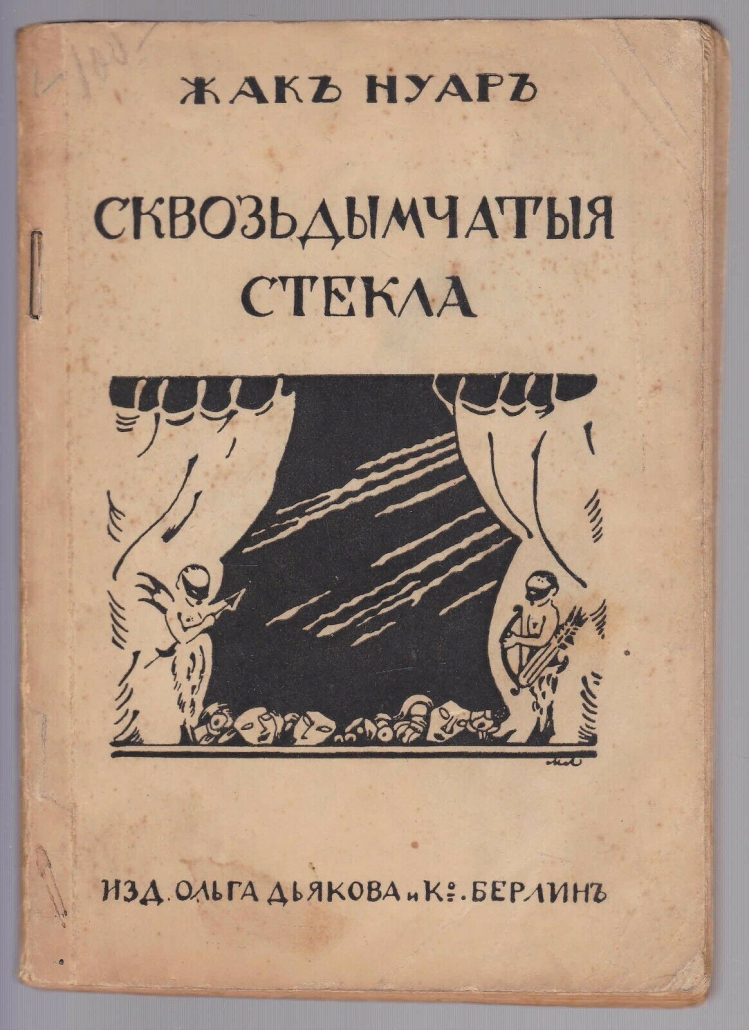

Skvoz dymchatye stekla, cover. – SBB: 426144

Oksner used his low profile to his advantage. He enjoyed being an invisible observer: “I like to stand on a busy intersection and watch passing trams scatter their shiny sparkles. I like to catch odd phrases in the humming of the crowd and spot pretentious postures, platitudes, fake laughter and flirtatious gazes” [“Na ulitse” (“In the Street”), Skvoz dymchatye stekla, Berlin, 1922, 89]. On the year of Oksner’s arrival to Berlin, his first poetry book, Skvoz dymchatye stekla [Through the Smoky Glass], published by Olga Diakova & Co, saw the light of day. The stencil on the soft cover of the pocket-size volume depicts a window doubling as a theatre stage; the window-sill, or proscenium, is strewn with masks; smiling masked cherubs are seen drawing back the curtains. The book’s eighty‑nine poems are grouped into nine sections, whose order loosely maps the poet’s mental and physical journey. Youthful bliss (the section “Spring Intoxication”) is followed by the tediousness of the “Province”, with its “narrow streets, dirty squares and ugly dwarfish houses pressed close together like a crowd of cowards looking for a chance to escape”. The poet’s relocation to a larger city – perhaps, Odessa or Chisinau – acquaints him with the petty bourgeoisie, night cafés and prostitutes (the section “City Blots”). The seasonal depression (the section “Under the Grey Sky”) is brightened by romantic aspirations and disappointments, explored in the three sections “Heart’s Notes”, “Vague Shadows” and “Random”.

In his poems, Oksner demonstrated curiosity, imagination and emotional intelligence. But he lacked erudition. Appreciating Oksner’s humility and sharp wit, his colleagues reluctantly pointed out the shortcomings of his writing. Oksner had a weak command of the Russian language, in spite of his well-known passion for the Russian literature. Having grown up in the provincial multilingual milieu without a proper education, he planted embarrassing lexical mistakes throughout his verses. Jacques Noir’s second Berlin book – the collection of one hundred romantic poems Kartonnyj paiats [Paper Jester], released in early 1924 – received harsh criticism from the poet Emiliia Kalmanovich: “The structure is amorphous, and the mastery is absent.” Quoting dozens of linguistic errors in Oksner’s poems, Kalmanovich (who signed her review with the pseudonym “Eskogor”) condemns his use of saccharine banalities and newspaper jargon but overall is charitable: “though much work lies ahead on the way of Jacques Noir becoming a poet, it is not a hopeless drudgery, but an inspired and promising enterprise” [Baltijskij Almanakh, No. 1, Dec 1923, 67–68].

The poems in Kartonnyj paiats (1924) communicate Oksner’s ideas on romance, memory, life’s cycles, changing fortunes and exile. They do this mostly through character studies of acquaintances, neighbors, strangers and imaginary persons. In the final pieces, evidently written in exile, the subjects change from the Russian provincials to émigrés. “Prodavshchica” [“Saleswoman”, 75–76] introduces a refugee aristocrat from Saint Petersburg, daydreaming while standing at the counter in a confectionery. Part of her daily routine is harassment by customers, and the highlight of her existence is the jokey conversation with the newspaper vendor who remembers her erstwhile noble status. The subject of “Oblomok” [“Splinter”, 76–77) is also a former noblewoman, who is now a courtesan and a hostess at a restaurant. Throughout the book, Jacques Noir has archetypal goddesses, queens, odalisques and seductresses acting in the classic narratives involving romance, treason, fate and death. But an occasional self-portrait suggests that the author is alone – and lonely – in his silent room, encountering merely fantasies and memories, immersed in the melancholy of displacement: “Scars in the past; gaps in the present… Life is a Christmas tree, and I am a paper puppet, suspended by the threads of my soul.” [“Bez elki” (“Without the Christmas Tree”), 134].

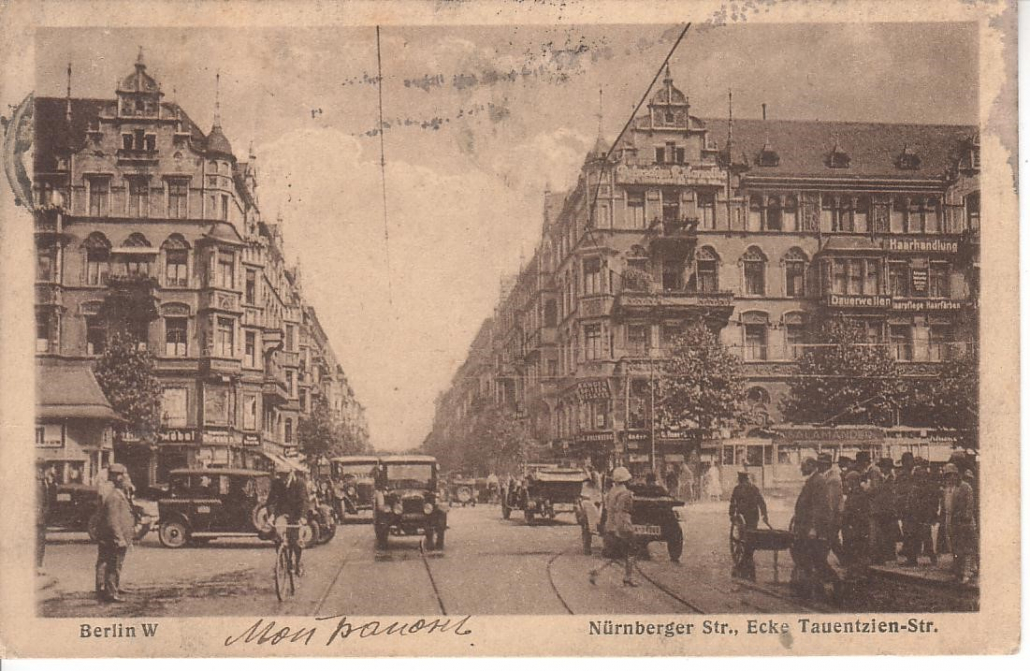

Postcard with the added handwritten inscription in Russian «Мой район» („My neighborhood“), sent from Berlin in 1928. – Courtesy of Stefan Brydolf, Vykortsmuseum. http://www.vykortsmuseum.se/old-postcards/101301.html

Oksner always struggled to make ends meet. His poems appeared in the widely read periodicals almost every week, but the fees offered by the émigré newspapers were insufficient for any comfortable living, especially in expensive Berlin. In 1926, an epigram by the satirical writer Leonid Munshtejn (known as Lolo) pointed out that Jacques Noir’s poetry displays “plenty of love for art, success and … money”, and warned that “it is only in their dreams that poets get marquises, princesses, cars and chateaus; life gives them holes in the coat and an endless rain” [Segodnia, No. 290, 23 December 1926]. The tragic and bizarre aspects of poverty are a recurring theme in Oksner’s verses. Poems like “Shtany” [“Trousers”] and “Chemodan” [“Suitcase”] glorify old tattered objects, treasured for sentimental reasons (“they are lonely and homeless, just like me”), before admitting that the owner simply cannot afford a replacement.

Oksner avoided Berlin cafés where many Russian writers gathered, and instead had dinners “at his German lady” [Arbatov]. This woman’s identity remains to be established, but her character might have entered Oksner’s poems about landladies, secretaries, flower sellers and other city types. She could be Fräulein Herta, the resident of 22 Kantstraße, the romantic heroine of the poem “Poslanie” [“The Message”]. Sympathetic to the struggles of single women in a big city, Oksner was one of the few literary Russians to pen compassionate lines about Berlin landladies, whom other Russian writers – including Ilia Ehrenburg, Vladimir Nabokov and Alexej Remizov – portrayed as greedy furies.

Corner of Tauentzienstraße and Passauerstraße, 1930s. – Photo:Willem van de Poll (onbekend). – Lizenz: Nationaal Archief, CC0 https://www.nationaalarchief.nl/onderzoeken/fotocollectie/aea29c14-d0b4-102d-bcf8-003048976d84

With the exception of Ehrenburg, no other Russian author in Berlin showed as much curiosity and respect for the host culture and the built environment. Jacques Noir’s poetic cycle entitled Litsom k Berlinu [Facing Berlin], released in January 1924, focuses entirely on the city of Berlin. Some of the twenty‑six poems included in this collection had appeared on the pages of Segodnia over the course of 1923. The book opens with an epigraph (in Russian) from Heinrich Heine: “O leave Berlin, with its thick-lying sand, weak tea and men who seem so much to know…” [1859 translation from the German by Edgar Alfred Bowring]. Litsom k Berlinu is a departure from Jacques Noir’s earlier generalized and somewhat stereotypical depictions of a city as a backdrop. Here the urban landscape is tactile and vivid; neighborhoods display their individual character. There are the orderly Sunday crowds in the Tiergarten, the tranquil majesty of Sans Souci, the frenetic illicit money changing in the Romanisches Café, and arrogant foreigners overrunning the National Gallery. The pace of urban life is examined in detail. The poem “Utro” [“Morning”] contrasts the orderly street layout and noble architecture with the misery of bread queues and anxiety of political rumors. The percussive rhythm in “Den” [“Day”] accentuates the stress of the office drudgery. “Vecher” [“Evening”] illuminates the class divide made visible by the brilliant street lighting and conspicuous consumption. “Noch” [“Night”] laments the debauchery in the clandestine brothels (Nachtlokale). The Russian refugees’ experience in Berlin includes a tragicomic search for an apartment (“In the name of Heinrich Heine, lend me some four walls”) and the dread of rising prices, leading to suicidal thoughts (“Smiling sadly, I bought a rope for seven million and hung myself”).

In the course of 1924, a single year, Oksner penned seven children’s books, published by Sever and Novaia Kniga. Three of these books – Detishki [Children], Krasnaya Shapochka [Little Red Riding-Hood] and Kolia i Olia. Detskie stikhi [Kolia and Olia. Children’s Poetry] – were once in the holdings of the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, but the physical copies were lost in the Second World War. It is likely his works for children were collaborations with Iurij Ofrosimov (1891–1967), the most prolific children’s author in Russian Berlin. Ofrosimov later described the production of such books as a slapdash process: “I was lying on my bed, he was lying on the couch; we cranked out these books without ever worrying about the didactic purposes. We reasoned that an exercise in rhyming helped improve our technique, therefore contributing to the art of poetry” [Korvin-Piotrovskij, Pozdnij gost, 1969, 261–262].

Exterior view of Café Wien, on Kurfürstendamm, in the1920s. – Source: Bildarchiv Preussischer Kulturbesitz. – Unknown author, Public domain

During the second half of the decade, Berlin entered the era of the Roaring (or Golden) Twenties, characterized by the fascination with technological progress, the spread of the culture of entertainment and the subversion of class and gender roles. Jacques Noir’s 1925 publication Prishchurennyi glaz [The Squinted Eye] is an ambivalent evocation of these times. The book subtitled Satira i Iumor features a laughing satyr mask on the cover, and the opening poem, “Za bortom” [“Overboard”], demands the reader to stop ‘brooding’ and to start dancing to the foxtrot rhythm of the world. The final lines, however, reveal that such merriment is feigned in order “to block out the cries for help of those thrown overboard”. Four years since the beginning of the Russian exile in Germany, the life of the émigrés in Berlin becomes increasingly bleak, reduced to “hopelessness, embarrassment, lethargy, poverty, melancholy, nostalgia, good intentions left for good, and whining, whining, whining” [“Tak bylo” (“So It Was”), 56]. As the misalignment with the host culture becomes more acute, a bitter voice is envious not only of “the doorman Hans, the red-cheeked saddle-maker Gerhardt, the blond printer Kurt and serious street sweeper Heinrich”, but even “the poodle of corpulent Amalia” [“Emigrantskaia zavist” (“Émigré Envy”), 66–67].

Priced out of Berlin’s theatres, cabarets and restaurants, the Russian émigrés rarely participated in the cultural highlights of the Roaring Twenties. For the poet, imagination fills the gaps in the personal experience. “Evoliutsiia tantsa” [“Evolution of the Dance”] follows the transition from minuet, gavotte, polonaise, mazurka and waltz to tango, foxtrot and shimmy. Playing off the title of the popular song Yes! We Have No Bananas (first performed in Berlin in 1923), Jacques Noir concludes that the culture of dancing has gone full circle and returned to the primates. In his typical manner, he reserves each poem’s last lines for a sceptical joke subverting or trivializing the romantic narrative constructed in the preceding stanzas. The poem “Izvechnoe” [“Eternal”, 19] starts with painting an amorous couple worshiping each other like gods and ends with the cynical: “The banknote he left on the table is a witness to yet another boring day.” The book’s female subjects are no longer heroines, but cunning and fickle wenches. The lines of “Intime” [sic!, 48] grumble: “I often watch the beautiful ladies fluttering along Kurfürstendamm like sparkling birds. But this drug is off limits to me: they take furs and diamonds in payment for their favors.”

However, the colorful urban scenes still hold attraction for Jacques Noir. The poem “Berlinskaia vesna” [“Berlin Spring”, 45] stacks up its short lines, as if hurrying to absorb the city in its complexity:

“…

Cars buzzing like bees,

their motors raging;

bunches of mimosas on the parapets.

A Comrade on the corner

spreading Communist leaflets;

a pipe in his teeth.

A crowd outside the movie ticket booth;

a beggar’s hurdy-gurdy whining in the courtyard;

children frolicking in the park.

Foreign ladies strolling

on Tauentzienstrasse,

accosted by schibers [currency speculators].

Vases on the balconies;

grey statues of frowning German classics

in the gardens;

the sun in the pale sky;

two water drops forming

the barbershop sign.”

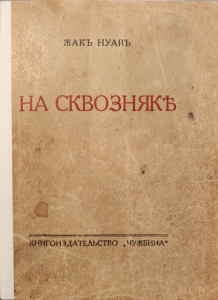

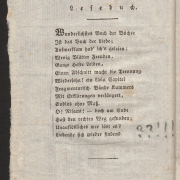

By the time Noir’s final poetry book, Na skvozniake [In a Drafty Place] (1927), saw the light of day, Russian publishing in Berlin had mostly ended. Reviewing Oksner’s book for Segodnia, Iurij Ofrosimov remarks on the mere pleasure of “opening a freshly printed volume with the Russian-language lettering” [Segodnia, No. 113, 21 May 1927].

Na skvozniake, cover. – SBB: 3 A 10691

Review in Segodnia, No. 113 (21 May 1927)

The spirit of dejection is palpable in the book’s title and even in the name of the publisher (Chuzhbina means “inhospitable foreign land”); the poems are divided into the sections “Longing for Change”, “Chance Smiles” and “German Vitrines”. The opening piece gives an ironic overview of the decade between 1917 and 1927 through the eyes of Russian refugees. After “fountains of speeches and flows of discussions” in 1917, they witness the triumph of the proletariat in 1918 and begin their exodus from Russia in 1919. The year 1920 brings them the “welcome salvation from the fear of the Bolsheviks” in Berlin. The year 1921 is marked by “the flowering of the publishing houses and a rich tapestry of books”; 1922 is the high moment for the Russian theatre and periodicals; there is also a growing political divide, as popular sympathy for Soviet Russia increases (the Changing Landmarks movement). The hyperinflation of 1923 gives an advantage to those Russians who saved some foreign currency (“We all knew our way to the Wechselstube”). But the next year crushes the “currency ecstasy” as the mark stabilizes, and soon the Russians are seen bringing the valuables to the pawnshops. By 1925, “everyone has left for Paris”. The final year, 1927, looks pessimistic: “Even Paris is now lean; after the Easter, the Lenten fast suddenly began.”

In 1931, Oksner accepted an invitation from his colleague Vladimir Despotuli to appear in the Cabaret of Russian Comics (Kabare russkikh komikov, or Ka‑Ru‑Ko) to act on stage alongside Iurij Ofrosimov and Viktor Iretskij. The performances were well-received. “It’s been a while since a Russian night was so delightful”, remarked the poet Sergej Gornyj, “The team has proven that Russians can display the German punctuality, precision and harmony” [Rul, 18 January 1931]. A few years later, Despotuli founded the pro‑Nazi newspaper Novoe Slovo, yet it was with his assistance that in 1936 Iakov Oksner succeeded in leaving the increasingly anti‑Jewish Berlin. He spent a few years in Bucharest, and then travelled further east, to Chisinau, the place where his journalistic career had started; located in Bessarabia, Chisinau was by then part of the USSR. In July 1941, a month after the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union had started, tens of thousands of Chisinau Jews were locked up in a ghetto and exterminated. Jacques Noir’s presumed year of death is 1941; he would have been fifty‑seven.

The rediscovery of his life and works was one of the fortunate outcomes of a research stay in Berlin in July and August 2021, enabled by the grant from the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, and the author owes the organizers her sincere gratitude.

Frau Ekaterina Knyazeva, Università del Piemonte Orientale, war im Rahmen des Stipendienprogramms der Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitzim Jahr 2021 als Stipendiatin an der Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin. Forschungsprojekt: „Spaces of the diaspora: urban form and cultural practices of Russian immigrants in Europe, Asia and America in the first half of the 20th century“

Online-Werkstattgespräch zur russischen Diaspora in der ersten Hälfte des 20. Jahrhunderts am 9. 8. 2021

![Covers of Jacques Noir’s books in the holdings of Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin: left –«Сквозь дымчатые стекла» (1922), [SBB: 426144]; right – «Прищуренный глаз» (1925), [SBB: 434371]. Center: portrait of the author, Iakov Oksner, from «Сегодня» [Segodnia], No. 113, 21 May 1927, National Library of Latvia. – Photos and collage: Katya Knyazeva](https://blog.sbb.berlin/wp-content/uploads/IntroREV-845x475.jpg) Ekaterina Knyazeva

Ekaterina Knyazeva

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/

Landesarchiv Berlin, einfaches Nutzungsrecht für SBB-Blog

Landesarchiv Berlin, einfaches Nutzungsrecht für SBB-Blog Public Domain 1.0

Public Domain 1.0 https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/mark/1.0/

https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/mark/1.0/

K:\IID\IID_2_Wissenschaftliche_Dienste\01_uebergreifendeAufgaben\Wissenswerkstatt\Social_Media\Blog\Blog ua Lektuere Tipps\Zeitungen

K:\IID\IID_2_Wissenschaftliche_Dienste\01_uebergreifendeAufgaben\Wissenswerkstatt\Social_Media\Blog\Blog ua Lektuere Tipps\Zeitungen

Ihr Kommentar

An Diskussion beteiligen?Hinterlassen Sie uns einen Kommentar!