Mobilised and Militarised Childhood: A Sample Schedule and Account of a 1960s-born Chinese Pupil in Two Days

Gastbeitrag von Dr. Sanjiao Tang

Driven by the international tensions in the Cold War context, war preparation elements heavily and continuously featured Chinese people’s lives throughout the Maoist era (1949–1976). Despite the great famine around the late 1950s, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) decided to include China’s entire population in the armed forces (quanmin jiebing 全民皆兵). In 1962, despite the tens of millions of deaths caused by the famine, the country celebrated that its militias had maintained a scale of over two hundred million people. It was not yet the final goal of the campaign of mass mobilisation and militarisation. As depicted in a well-known slogan, all the seven hundred million Chinese people were to become soldiers (qiyi renmin qiyi bing 七亿人民七亿兵). Although this was rhetorically exaggerated, it is no exaggeration to say that Chinese people were generally involved in the national war-preparing activities that lasted until the end of the Maoist era, and whose relevant experiences should not be overlooked when reviewing personal and collective lives in Maoist China. It is also the topic that I aim to explore.

Before arriving in Berlin, benefiting from a notable number of sources I had collected, my research mainly concentrated on those joining the militias who were normally aged between 16 and 35 and undoubtedly formed the core force of Maoist-era mass mobilisation and militarisation. As for those either too young or too old to obtain membership of the militias in the Maoist era, how were their lives associated with the mass campaign? For example, what were the Chinese children’s stories like between the 1960s and 1970s, being engaged in the war preparation? Remember the active roles that schoolchildren in elementary and junior middle schools had played in China’s numerous mass movements since 1949, like their organisational participation in the movement of backyard furnaces during the Great Leap Forward in the late 1950s. It was not surprising that the children from the early 1960s took another active part in the national campaign of mobilisation and militarisation, as the youngest generation involved in the war-preparation activities. However, their stories scarcely received much attention in the officials’ paperwork and documentation. Hardly could these pupils carefully record their experiences either. Overlooking the mobilised and militarised childhood of the generations who are driving the country at present leads to a notable gap in understanding both Maoist and today’s China.

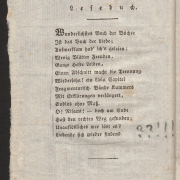

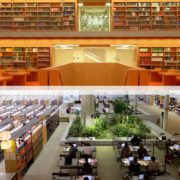

Thanks to the Grant Program of the Stiftung Preussischer Kulturbesitz, I had the opportunity to conduct my research at Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin and to access valuable contemporary publications regarding the Chinese school pupils being mobilised and militarised between the 1960s and 1970s. Whether they are in the form of picture-story books or children’s fiction, whether they have been issued periodically or published separately, they are all in scouts-like style. The Chinese word xiao bing (小兵), meaning ‘young soldiers’ in English, frequently appeared in their titles. Taking up a big proportion of them are monthlies or semi-monthlies produced in various provinces during the Cultural Revolution period (1966–1976) that are aiming at children in primary schools, uniformly with the name of Hong Xiao Bing 红小兵 (see illustration above). When Hong Xiao Bing is mentioned, people will normally think about Hong Wei Bing (红卫兵 Red Guards), who were the rebels in China during the first few years of the Cultural Revolution. Younger than those becoming Hong Wei Bing, Hong Xiao Bing were the youngest participants of the Cultural Revolution. In December 1967, the authorities endorsed the Hong Xiao Bing organisations in primary schools, aiming to recruit those between 6 and 12 years old. While the tide of the Cultural Revolution ended in the late 1960s, that was also the time when the Hong Xiao Bing organisations truly functioned in China’s elementary schools. Until the late 1970s, despite the decline of the Cultural Revolution, the lasting campaign of mass mobilisation and militarisation instead characterized the Hong Xiao Bing organisations. As a result, the Chinese generations starting their primary schooling between 1966 and 1976 had common and distinct experiences of their preparation to defend Maoist China as Hong Xiao Bing.

Admittedly, all these items were propaganda products of the CCP. For the curious children, when most cultural products and literary works were banned during the Cultural Revolution, these publications were also among the very scarce materials they could read every day. What was propagated in these books provided them with limited and precious information regarding what to learn, what to play, what to say, what to sing, what to know, and what to dream about.

Therefore, based on the materials in the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, I tried to draw up a sample schedule and account of a Chinese pupil of two days during the first half of the 1970s, when the order of schooling had been basically recovered from the chaos caused by the Cultural Revolution. – Imagine that you started your primary education in the early 1970s: You will find that your school lives were driven by ubiquitous elements of mobilisation and militarisation, which aimed to physically and mentally train you according to the need of war preparation.

- Day One, 9:00–11:00 am

This session is based on:

Chen Guangrong 陈光荣 (text), Mei Meng 梅萌 (images), “Jianpuzhai xiaoyingxiong: Dada” (柬埔寨小英雄: 达达) (‘Young Hero in Cambodia: Dada’), Hong Xiao Bing (红小兵) (Issued by Jiangsu Province) 53, no. 8 (1975): no page number available

As the most important thing that all the children need to do in school, the session of Studies in Politics (Zhengzhi xuexi政治学习) takes place at least three times per week. This morning, the Studies in Politics in your class focuses on mobilising the children to play an active role in national defence. Your teacher’s long speech based on the upper-level documents is boring to the class. What draws your attention is the story shared by your teacher. It is about a child fighting hero in Cambodia. Your teacher retells the story based on a Hong Xiao Bing magazine. The Cambodian child learned and mastered the skill of driving a tank in just a few days, by which he contributed significantly to defend the communist regime in Cambodia, Khmer Rouge (Hongse Gaomian红色高棉). At that time, none of you really knows the regime of the Khmer Rouge, which killed millions of people in Cambodia. Yet, the ignorance does not prevent you from admiring the child fighting hero. To defend the Chinese communist regime, now you understand that you need to improve yourselves and learn from the child fighting models of the Khmer Rouge. The sessions of Studies in Politics are also one of the very limited ways for you and your classmates to obtain information regarding the outside world, although what you hear from the teacher is usually partial, fake, and misleading.

- Day One, 1:00–2:30 pm

This session is based on:

Lu Xiaoping 陆小萍, “Wo tiaoguo le shanyang” (我跳过了山羊) (‘I vaulted the horse’), Hong Xiao Bing (红小兵) (Issued by Guangdong Province) no. 1 (January 1974): 34–35

The first session after lunch is PE class. Today, the task is to practice tiao shanyang (跳山羊 horse-vaulting), which is a common requirement in military training. You have learned the basic skills in previous classes. But you still lack confidence in practice. In order to encourage you, the PE teacher uses the example of battlefields. According to your teacher’s analogy, it is just like how the soldiers stride over barriers in warfare. So, to be better prepared for the coming war, you must take the challenge of tiao shanyang and achieve the goal. Being effectively encouraged, you successfully finish the task when imagining that you are really in a battle fighting against enemies.

- Day One, 3:00–4:00 pm

This session is based on:

Cui Yaofa 崔耀法, “Wa dilei” (挖地雷) (‘Dig up land mines’), Hong Xiao Bing (红小兵) (Issued by Guangdong Province) no. 8 (August 1974): 4, and “Yiqie xingdong ting zhihui” (一切行动听指挥) (‘All actions under command’), Hong Xiao Bing (红小兵) (Issued by Jiangsu Province) 47, no. 2 (1975): no page number available

After the PE class, there is a one‑hour period for collective activities. Aiming to reinforce the cohesion and teamwork of the pupils, teachers organise a series of interesting games in group form, which are always welcome by the children. This time, two new games are recommended. The first one is Wa dilei (挖地雷 Dig up land mines). As instructed by your teacher, the pupils, including you, sit in a circle. Two bricks are put inside as landmines. Each time, two children, with their eyes covered, try to find the landmines with their hands. When it is your turn, you move your hands slowly and cautiously, as if you were really in a minefield. When you finally dig up a land mine, all your classmates applaude for you, just like a cohesive team fighting together in a war.

The second game is even more militaristic. The name of the game is Yiqie xingdong ting zhihui (一切行动听指挥 All actions under command). It is quite a large-scale collective game, in which a whole school class can participate. Every child holds a wooden gun and stands in a line. Every line of children is regarded as a military squad. Once your teacher issues the order of zhunbei zhandou (准备战斗 prepare for fighting), each line moves according to the whistling. There are different kinds of whistling sounds with different meanings, like one long, two short, or one long and one short. They signify taking a step forward, taking a step back, about‑face, and some other actions. All the children are expected to take actions correctly, timely, and precisely in line with the orders. Due to nervousness, you make a mistake when moving. You feel guilty and decide to take more exercise. Only in this way you can make fewer mistakes in real wars, you believe. Otherwise, your comrades-in-arms would be endangered.

- Day One, 6:00–7:00 pm

This session is based on:

Zhang Chi 张翅, “Tebie renwu” (特别任务) (‘Special Task’), Hong Xiao Bing (红小兵) (Issued by Guangdong Province) no. 8 (August 1974): 14–15

After school, the hong xiao bing in your class, including you, receive a special task (teshu renwu特殊任务). It is to protect the crops in collective fields. Despite your young age, you are expected to finish the task together with the militia members in your village. Not only is the name of the task military-like, you are also requested to behave as if engaging in a fully militarised assignment in warfare. Based on the militia cadres’ instruction, what you specifically need to do is to go around on patrol, keeping vigilant at all times about any potential destruction from class enemies (jieji diren阶级敌人).

- Day Two, 9:00–10:30 am

This session is based on:

“Fanxiu qianxian de Hong Xiao Bing – Zhenbaodao diqu Hong Xiao Bing de gushi” (反修前线的红小兵 – 珍宝岛地区红小兵的故事) (‘The Hong Xiao Bing on the frontier of anti-revisionism – the stories of Hong Xiao Bing in Zhenbaodao region’), in: Women shi Maozhuxi de Hong Xiao Bing (我们是毛主席的红小兵) (‘We are the Hong Xiao Bing of Chairman Mao’), Shanghai: Shanghai Renmin Chubanshe, 1970: 1–6, and “Jizhi de Xiaowulan” (机智的小乌兰) (‘The smart Xiaowulan’), Hong Xiao Bing (红小兵) (Issued by Jiangsu Province) 50, no. 5 (1975): no page number available

In the Chinese class this morning, your teacher introduces extra reading materials, two stories from Hong Xiao Bing magazines. Based on close reading and comprehension, you should answer questions related to the keynotes of the stories.

The first story is about the hong xiao bing who joined the fighting with the Soviet Union on China’s northeast frontier, Zhenbao Island, in 1969. It is certainly a fiction, as it would be an extremely crazy thing to let children participate in a conflict between regular armies where tanks and armoured cars were used. Nevertheless, many pupils in your class are deeply moved and stimulated by the fictional story, swearing that they would defend China as heroically as the peers described here.

As for the second reading material, it is a picture story set on the grassland in Inner Mongolia. The hong xiao bing there are also active in war preparation and national defence. As a significant result of their efforts, a spy is discovered and arrested by the Mongolian hong xiao bing. After you have enjoyed the thrilling story, your teacher repeatedly highlights the importance of staying alert to any potential spy that you might meet in your daily lives.

- Day Two, 1:00–2:00 pm

This session is based on:

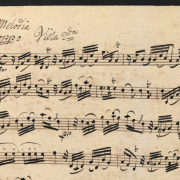

Hong Xiao Bing yue zhan yue jianqiang: ertong gequ huoye gequ (红小兵越战越坚强: 儿童歌曲 活页歌曲) (‘The more fighting, Hong Xiao Bing are stronger: loose-leaf of children’s songs’) (3), Beijing: Renmin yinyue chubanshe, 1974

After lunch, your first session is a music class. This is your favourite session across the curriculum, as you like singing. Many of the songs that you learn in the class are inspired by military-related themes. Even though some songs do not present real warfare directly, they still strongly encourage you to fight (zhandou 战斗), no matter if you have been mobilised to attend meetings of criticism (pidouhui 批斗会), criticise Lin Biao and Confucius (Pilin pikong 批林批孔), or prepare to go to the countryside (Shangshan xiaxiang 上山下乡). In the mass mobilisation and militarisation context, such analogies were not weird but produced harmonious melodies. Whenever singing these songs loudly with your classmates, you feel agitated and become eager to join the fighting.

- Day Two, 2:30–5:30 pm

This session is based on:

“Jixun qianjin” (继续前进) (‘Continue advancing’), in: Women shi Maozhuxi de Hong Xiao Bing (我们是毛主席的红小兵) (‘We are the Hong Xiao Bing of Chairman Mao’), Shanghai: Shanghai Renmin Chubanshe, 1970: 114–117

For your classmates and you, the music class is yet the most attractive part of this afternoon. After that, you would go hiking, as one of the collective activities that enjoy lasting popularity among all the pupils in your school. Instead of taking a relaxing leisure activity, however, according to the instructions issued by your teacher who leads the hiking team, it is not an ordinary hiking experience but a fighting task with the aim to occupy the hill from the enemies. But who are the enemies? Based on the instructions, the U.S. and the Soviet Union are regarded as the enemies that the children need to fight. Resulting from the real war-like mobilisation, the whole way of climbing up the top of the hill is filled with your yell of kill, kill, and kill (hanshasheng zhentian喊杀声震天). Finally, in your imagination, you successfully defeat the U.S. and Soviet Union enemies and “occupy” the top of the hill as expected. Even so, that is not the end of the “fighting” task. As instructed by your teacher, the goal of defeating the enemies has not been fully achieved yet. Next week, your class will participate in another hiking activity under the title of jixu qianjin (继续前进 continue advancing).

- Day Two, 6:30–8:00 pm

This session is based on:

“Dixiashi de zhandou” (地下室的战斗) (‘The fighting in the basement’) and “Da huoba” (打活靶) (‘Alive target practice’), in: Women shi Maozhuxi de Hong Xiao Bing (我们是毛主席的红小兵) (‘We are the Hong Xiao Bing of Chairman Mao’), Shanghai: Shanghai Renmin Chubanshe, 1970: 133–137 & 14–21

Finishing the “fighting” on the hill, it is not yet time to go back home. This week, your class is responsible for the school’s propaganda task. After the lessons, you need to produce big character papers (dazibao 大字报) and slogans, in addition to completing other relevant work for propaganda. All you are going to do is described as fighting tasks (zhandou renwu 战斗任务). When the topic of the big character paper is to criticise certain people, it is called daba (打靶 target practice), as serious as the situation in warfare. Sometimes, you even have the chance to help organise in-person meetings to criticise those who are viewed as anti-revolutionary in your school. In that case, it is called da huoba (打活靶 alive target practice). You and all your classmates yearn for such opportunities, which are no less exciting than getting a chance to fight against enemies in a real war.

As shown in this sample schedule and account of only two days, it is already safe to conclude that although just between 6 and 12 years old, Chinese children were shaped by war-preparing elements during their school lives in various aspects, including the knowledge they learned, the skills they acquired, their reading preferences, their habit of speaking, and their mode of thinking. If the Maoist era had not abruptly ended after a few years and the mass mobilisation and militarisation had continued, these children in their adolescence and early adulthood would surely have become the main force of war preparation in Communist China. The unexpected end of the Maoist era suddenly stopped them on the way to achieve their goal. Hong Xiao Bing organisations were dissolved nationally in 1978. However, the influence of the mobilised and militarised childhood may not be so easily overcome.

Benefitting from the rich materials existing in the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, only a small part of which is demonstrated in the article here, I plan to conduct more detailed research focusing on the experiences of Chinese children involved in China’s mass mobilisation and militarisation under Mao, in addition to the legacies that live beyond the Maoist era.

Links to the referred sources available at the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin

Hong Xiao Bing (红小兵) (Issued by Guangdong Province), no. 1 (January 1974). –

SBB-PK: Zsn 47135-1974,1

Hong Xiao Bing (红小兵) (Issued by Guangdong Province), no. 8 (August 1974) . –

SBB-PK: Zsn 47135-1974,8

Hong Xiao Bing (红小兵) 47 (Issued by Jiangsu Province), no. 2 (1975) . –

SBB-PK: Zsn 129438-47 (2,1975)

Hong Xiao Bing (红小兵) 50 (Issued by Jiangsu Province), no. 5 (1975) . –

SBB-PK: Zsn 129438-50 (5,1975)

Hong Xiao Bing (红小兵) 53 (Issued by Jiangsu Province), no. 8 (1975) . –

SBB-PK: Zsn 129438-53 (8,1975)

Hong Xiao Bing yue zhan yue jianqiang: ertong gequ huoye gequ (红小兵越战越坚强: 儿童歌曲 活页歌曲) (The more fighting, Hong Xiao Bing are stronger: loose-leaf of children’s songs), Beijing: Renmin yinyue chubanshe, 1974. –

SBB-PK: 229838

Women shi Maozhuxi de Hong Xiao Bing (我们是毛主席的红小兵) (We are the Hong Xiao Bing of Chairman Mao), Shanghai: Shanghai Renmin Chubanshe, 1970. –

SBB-PK: 220150

Herr Dr. Sanjiao Tang war im Rahmen des Stipendienprogramms der Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz im Jahr 2024 als Stipendiat an der Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin. Forschungsprojekt: „An Exploration of China’s Campaign of Mass Mobilization and Militarization during the Mao Era: Based on the Valuable Sources at the Berlin State Library“

Vortrag im Rahmen von CrossAsia Talks am 14. 5. 2024

Foto: Sanjiao Tang

Foto: Sanjiao Tang

Public Domain 1.0

Public Domain 1.0 Public Domain Mark 1.0

Public Domain Mark 1.0 https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/mark/1.0/deed.de

https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/mark/1.0/deed.de

Bildausschnitt: Aquarell Breslau, Zuchthaus. Aus: Stridbeck, Johann: Skizzenbuch : Ms. boruss. qu. 9a , 1691. SBB-PK

Bildausschnitt: Aquarell Breslau, Zuchthaus. Aus: Stridbeck, Johann: Skizzenbuch : Ms. boruss. qu. 9a , 1691. SBB-PK

Ihr Kommentar

An Diskussion beteiligen?Hinterlassen Sie uns einen Kommentar!