Relations between the Ottoman Empire and Germany, 1908-1918: Artistic Interaction and Cultural Institutions

Gastbeitrag von Özge Gençel

At the end of the 19th century, when the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire accelerated, voices opposing the sultan increased gradually. The first organised opposition of the Empire, the Committee (or, Party) of Union and Progress (Turkish: İttihat ve Terakki Cemiyeti) played a role in the declaration of the Second Constitutional Monarchy on 23rd July 1908. In the Second Constitutional Era (1908‑1918), a great number of reforms were realized in various fields, and mostly the German Empire was taken as a model, due to the impact of the Committee of Union and Progress. The party became gradually closer with Germany of whom the Ottoman Empire would be an ally during World War I. Right along with diplomatic, economic and military grounds, the alliance between the Ottoman Empire and Germany played a role in cultural interaction. In this context, a series of artistic events took place and a number of attempts were made to found new cultural institutions or to renew the existing ones.

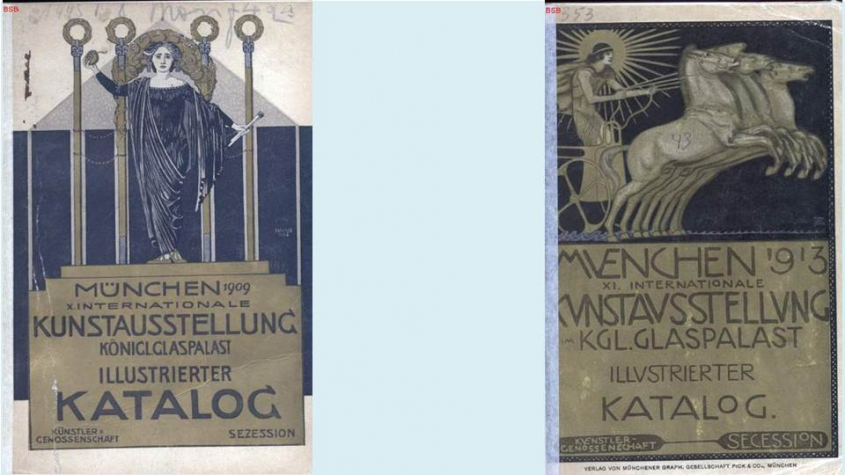

An important event that allows to clearly observe this cultural interaction are the International Art Exhibitions in Munich (Internationale Kunstausstellungen im Königlichen Glaspalast zu München), which had taken place since 1869 at intervals. The Ottoman Empire was invited to these exhibitions for the first time in 1909, which was the 10th International Art Exhibition in Munich. The figure who provided the invitation for the Ottoman Empire was Max Kemmerich, Honorary Consul General of Germany. Announcing the good news, Kemmerich emphasized how important these exhibitions were, and participating in them along with the “developed” states was a great way for the Ottoman Empire to show improvements in the Empire to the western countries.

It seems that the Ottoman Empire found it important to participate particularly in these exhibitions, as there were some more invitations from other countries to exhibitions which the Empire did not attend. For the participation in the Munich exhibition, the Imperial Museum (Turkish: Müze-i Hümayun) was assigned. At first sight it does not make much sense because the Ottoman Imperial Museum was an archaeological museum, and the Munich exhibitions were displaying painting, sculpture, architecture and handicrafts. However, at that time the museum was under a common directorate with the Imperial School of Fine Arts (Turkish: Sanayi-i Nefise Mektebi), and as it is to be seen from the catalogue of the Munich exhibition, most of the artists whose paintings were taken to Munich were either teachers or graduates of this school.

Founded in 1883 and modelled upon the French École des Beaux Arts, the Ottoman Imperial School of Fine Arts was still trying to establish its own tradition at that time. Hence, it is an important question to ask how the artistic production of Ottoman artists was perceived among the art works of other countries. In this context, the large periodical collection of Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin helped to reveal the perspective (for the digitized historical newspapers see: http://zefys.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/index.php?id=list, and for the collection of art journals see: http://ark.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/index.php?ebene=002.011.010.020&ACT=&IKT=&TX=&SET=&NSI=SYS). It seems that even if the Ottoman Empire was invited to the exhibitions with praises to its art scene and artists, the art critics of the time weren’t satisfied with the Ottoman art exhibited. Following the 1909 exhibition, one of the most remarkable comments on the Ottoman pavilion emphasized not the artistic values but the courage and honesty of a state that had recently been incorporated in this international art exhibition:

“The first appearance of the Bulgarians and Turks was noted as a curiosity. It would be wrong to underestimate the courage and honesty of these artists, which have to be measured by other standards” (Kunst und Künstler, August-1909).

Another comment stated that the Ottoman exhibition was not interesting and the Bulgarian one was only a little bit more engaging (Die Kunst für Alle, November-1909). Still, the Ottoman Empire received an invitation to the following, 11th International Art Exhibition in Munich in 1913. Yet, once again art critics were not satisfied, it was written that Turkey was not only politically but also artistically in a bad situation (Die Kunst für Alle, September-1913).

Meanwhile, mutual interest between the two states increased continuously. In February 1914, the German-Turkish Association (Deutsch-Türkische Vereinigung) was founded in Berlin. It basically focused on helping the education system of the Ottoman Empire, identifying it as the most important issue in re-forming the Empire. The Committee of Union and Progress had already adopted this idea as well and decided to carry out some reforms in education. As a result, in 1914, at the request of the Committee of Union and Progress, Prof. Dr. Franz Schmidt was assigned to reconstruct the Turkish education system in compliance with the German model. In October 1915, the Turkish-German Association was founded in Istanbul as a branch of the association in Berlin. However, this time Turkish specialists were more efficient in designing the program. As the main aim it was determined to preserve the ongoing communication between the two nations and to introduce them to each other with the help of cultural activities such as exhibitions, film screenings and lectures. For example, as the Berlin Academy Archives revealed, in 1917 it was planned to display Ottoman paintings in Berlin, although it could not take place probably because of the war. However, in 1918 an exhibition of artists from Munich was organised in Istanbul.

In the meantime, Muslihiddin Adil Bey, director general of secondary school education, went to Germany and carried out some investigations. Muslihiddin Adil Bey visited more than a hundred education institutions in Berlin, Dresden, Leipzig, Hamburg, Munich, Frankfurt, Heidelberg, Wiesbaden and Stuttgart. Following two study visits, in 1917 he wrote a book about the German education system, with the Turkish title Alman Hayat-ı İrfanı (“German Life of Education”), which can be seen as one of the key documents for understanding the cultural and educational reforms in the Empire. According to Adil, necessary reforms in the education system, starting from the university and including every aspect of education, had to be based on both national culture and western science. One of the main purposes leading Ottoman bureaucrats saw in the reforms in the education system was to highlight the nationalist ideas in the Ottoman Empire, and to eliminate French elements from Turkish culture. The research in Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin established that, in accordance with the Zeitgeist of the period, both countries had the similar discussion about shaping their own culture free from foreign influences, especially from French influences, which must have been serving as one of the common grounds that made these two countries go closer in the cultural sphere. Hence, it was thought that the Ottoman Empire needed to realize the necessary renewal by modelling on German education, science and art while protecting its own history, culture, religion and nationality. In his guiding book, Muslihiddin Adil Bey wrote about the way the educational and cultural institutions were managed, and he mentioned how important it was to give female students opportunities in higher education. He not only provided information about various types of schools in Germany, but by giving detailed descriptions of museums as well as monuments and art in public spaces, he also emphasized their educative function.

In the scope of this research, it is a significant question how the Imperial School of Fine Arts was affected by these institutions and by the new path. As the one and only fine arts school of the Empire, it was surely included in the program. It was planned that students of the Imperial School of Fine Arts would visit Germany, and German students would visit the Ottoman Empire. Moreover, it was decided that a German artist was to be the head of the school. Although these plans could not be carried out due to the conditions of war, still the Imperial School of Fine Arts went through some changes.

First of all, it has to be noted that, mostly in consequence of the school’s own dynamics but also in parallel with the intellectual change in the Empire, a younger generation of teachers was employed. As graduates of the Imperial School of Fine Arts, they were criticizing their own teachers and the education they had received, demanding a more nationalistic art. It is not possible to say they especially took the fine art schools in Germany as a model though: The well-accepted systems of the fine art academies of that time were mostly similar to each other, and there were not any fundamental changes in curricula. The question was mostly about the content and, as Ottoman artists/teachers had received further education in France, they wanted to re-create the Ottoman art with the help of some techniques they had learnt in France.

On the other hand, it seems that these interactions had a stronger effect on institutional management. In 1914, a department for female students was founded as an affiliate institution (Turkish: İnas Sanayi-i Nefise Mektebi) of the Imperial School of Fine Arts. In 1915, the Museum of Painting was founded within the same structure as the school. In 1917, the Imperial School of Fine Arts was separated from the Imperial Museum and became an independent institution. In 1918, Ömer Adil Bey, the head of girls’ fine arts school, was sent to Germany for the purpose of making investigation on fine arts education and providing necessary materials and tools for the school.

Considering all these interactions and cultural policies of the Ottoman Empire together, it is not surprising that in 1917 the Ottoman Empire decided to found cultural institutions such as a national museum, a museum of ethnography, a national library, and a directorate to organise and run these institutions. Although most of these projects remained unfinished for some time because of the tough conditions of wartime, it seems that the Ottoman Empire put the cultural institutionalism on its agenda and decided to follow the German model in this sense.

Frau Özge Gençel, Çanakkale Onsekiz Mart Üniversitesi, war im Rahmen des Stipendienprogramms der Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz im Jahr 2019 als Stipendiatin an der Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin. Forschungsprojekt: „Mekteb-i Sanayi-i Şahane (Sanayi-i Nefise Mektebi Âlisi) / The State Academy of Fine Arts“

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/deed.de

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/deed.de  CC-BY-NC-SA

CC-BY-NC-SA CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 CC BY-SA-NC 3.0

CC BY-SA-NC 3.0

https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/mark/1.0/deed.de

https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/mark/1.0/deed.de

Bildausschnitt: Aquarell Breslau, Zuchthaus. Aus: Stridbeck, Johann: Skizzenbuch : Ms. boruss. qu. 9a , 1691. SBB-PK

Bildausschnitt: Aquarell Breslau, Zuchthaus. Aus: Stridbeck, Johann: Skizzenbuch : Ms. boruss. qu. 9a , 1691. SBB-PK

Wissenswerkstatt Schulung SBB-PK CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

Wissenswerkstatt Schulung SBB-PK CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

Ihr Kommentar

An Diskussion beteiligen?Hinterlassen Sie uns einen Kommentar!