Political agency through representation: Emperor William I as monarchical political actor

Gastbeitrag von Frederik Frank Sterkenburgh, The University of Warwick

Scholarly literature with regard to German Emperor William I shows an important discrepancy. On the one hand, William is considered politically feeble because of his chancellor Otto von Bismarck’s overbearing personality. According to this point of view, he grew, from 1871, an imperial figurehead, albeit an unwilling one. On the other hand, historians such as Andreas Biefang and Alexa Geisthövel have demonstrated that William consciously sought to craft his public image making use of the emerging mass printed media. From this angle, much greater agency appears to be ascribed to the monarch. Both perspectives follow a wider body of scholarship that sees monarchs in the second half of the 19th century as growing into symbolic figureheads with declining political powers, while also being forced to adapt to the changing media landscape. This begs the important question whether we need a more differentiated definition of political agency. A renewed look at the sources allows us to reconsider these arguments with regard to 19th century monarchs in general and William I in particular.

To develop a new definition of monarchical political agency, we can draw on cultural approaches to political history. Barbara Stollberg-Rilinger has argued that all political entities depend on representation in order to become a political reality. Only through representation a political order can be mediated in a conceivable manner. To this end, all political representations depend on symbolic acts in order to emphasize the particular political order they seek to create and reaffirm. Andreas Biefang has defined symbolic acts as all forms that are connected with political communication, such as language, architecture and ceremonial. Importantly, such representations need to be perceived by and resonate with the intended audience in order to become effective. Defining political agency in this manner allows to establish which groups are deemed instrumental in upholding the political order. Such a definition is particularly applicable to William, for whom relying on institutional or geographical dominance was of little use to effectuate his political agency because of Bismarck’s dominant role in the governmental executive, on the one hand, and the persistence of other German states, dynasties and identities after 1871, on the other.

The Newspaper Department of the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin provides a rich corpus of contemporary material to subject this definition to scrutiny of the sources. In particular, the wide variety of newspapers with different political, regional and religious backgrounds offered a chance to consider in what manner and to which audiences William communicated the political order that he stood for, so as to make both his role as imperial figurehead and the monarchical form acceptable to as large a part of the population as possible. In addition, through the detailed descriptions of events that many 19th century newspapers provide, they fill in gaps in knowledge not provided by archival sources, such as about clothing or gestures. In the context of cultural history and cultural approaches to political history, these are important indicators of how power structures, political orders and the accompanying discourses are communicated.

An example drawn from newspaper accounts can make this clear. In 1876, the annual military manoeuvres were held for the first time outside Prussia, so as to include military units from other German states and contribute to the integration of the German Empire. William attended these military manoeuvres as they offered him a chance to acknowledge the other German states and dynasties. Newspaper accounts provide the details: He did this, amongst other things, by wearing the uniform or medals from the respective state he visited. As the Kreuzzeitung described the manoeuvres held in Saxony in 1876, ‘Se. Maj. der Kaiser und König, welcher durch Seine auch hier allgemein in Erstaunen setzende Frische und Rüstigkeit Freude in weitesten Kreisen und Jubel hervorrief, trug preußische große Generals-Uniform mit den Abzeichen eines General-Feldmarschalls, das lichtblaue schmal gelb geränderte große Band des K.sächsischen Militär-Heinrich-Ordens, die preußischen Kriegs-Orden und das Großkreuz des Heinrich-Ordens mit dem Lorbeerkranze, das einzige, welches mit diesem Schmucke vorhanden ist, und welches König Johann dem König Wilhelm am 9. October 1870 verliehen hat.’ Upon his departure from Leipzig after the military manoeuvres, William had published a letter to the mayor, written by either himself or the cabinet, which included his statement that ‘Mir ist hier, wo vor 63 Jahren der erste Schritt für die Vereinigung Deutschlands mit blutigen Opfern erkämpft wurde, überall eine so wohlthuende Darlegung der Sympathie für die Einigkeit Deutschlands, verbunden mit warmer und treuer Anhänglichkeit an den Landesherrn entgegengetreten, daß es Mir, ein wahres Herzensbedürfniß ist, Meiner freudigen Befriedigung hierüber Worte zu geben. Der Name der Stadt Leipzig ist bisher jederzeit unter den ersten genannt worden, wo es die Ehre und Größe Deutschlands galt.‘

Such newspaper accounts give insight into William’s political agency in two respects. First, they demonstrate how he acknowledged the dynastic-federalist nature of the German Empire. Through descriptions of the uniform he wore and the medals he had pinned on his uniform, it can be established that William used these symbols to acknowledge and underline the dynastic-federal character of the German Empire. Although the example quoted here applies to Saxony, we may assume that similar acts were carried out with regard to other German states. This suggests an active approach of William to the construction of the German Empire and challenges arguments about him as a Prussian king being a reluctant German Emperor.

The second point is the historical narrative provided by the letter William had handed to the mayor. Important here is the reference to the Napoleonic wars, and the battle of Leipzig in 1813 in particular, which is presented as a stepping stone towards eventual German unification in 1871. In this manner, William contributed to the construction of a historical narrative in which Prussia’s role in German history was underlined. Although such messages were readily relayed in private, they were written with the intention of being published in newspapers. There is a specific importance in the fact that these symbolic acts were noticed, both by the audience directly present and in newspaper coverage. Therefore, newspaper coverage provides a means to gauge to what extent William’s use of symbolic acts was circulated and popularized.

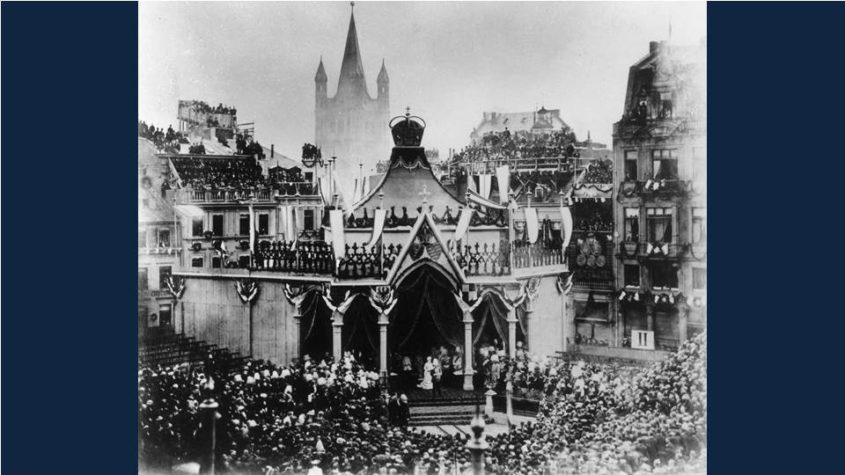

A further result of the research conducted in the Newspaper Department are much richer contours of how William framed his status and his monarchical power in relation to different geographical, religious and historical contexts. An example can illustrate this. In October 1880, William attended the dedication of the Cologne Cathedral. The Kölnische Zeitung wrote that ‘Wer immer seit zwei Mensenaltern ein Herz und einen guten Wunsch hatte für das deutsche Vaterland, der hatte auch ein Herz und eine Gabe für den Dom von Köln, und es war eine bedeutsame Fügung in dem Geschicke der Völker, das des deutschen Reiches Gründer auch des Kölner Domes Vollender sein sollte, dieses schicksalvollen Wunderwerkes, das wie kein zweites seit der ersten Grundsteinlegung bis zur Krönung seiner Türme ein Wahrzeichen und Symbol gewesen des deutschen Reiches und der Geschicke der deutschen Nation’. By contrast, the Frankfurter Zeitung wrote, more perceptively, that ‘Dieser Feier, die eine kirchliche sein soll, wohnte der Klerus nicht bei. Im Dom waren heute die zelebrierenden Priester zugegen und ein Weihbischof, welcher Kaiser Wilhelm empfing, im Uebrigen, zeigte sich weder in den Straßen, noch auf dem Festplatze ein Geistlicher. Zog man die große Menge aufgebotenen Militärs und die in Uniform erschienen Fürstlichkeiten in Betracht, so konne man eher an ein militärisches Fest glauben…’ Apart from such diverging appreciations, it is also telling that the Kölnische Zeitung spent several pages on its coverage, while the Frankfurter Zeitung’s comments come from the barely three columns on the bottom of its front page covering the event. This not only reflects these newspapers being of Catholic and of liberal orientation respectively, but also the one being a local and the other a national newspaper.

These divergences in treatment are significant in so far as they point to the workings of William’s political agency. The examples of the newspapers demonstrate that William’s symbolic acts were picked up by newspapers differently, contributing to them being circulated to a wider audience. As such, newspapers helped give contours to William’s imperial role, adapting it to different regions, social groups and confessional belongings. They helped shape perceptions of the monarchy, but it is not simply the case that newspapers forced the monarch to react. The examples demonstrate that William used this medium clearly to his own advantage. Newspapers thus extended the political leverage of the monarch, representing not just national audiences, but regional and local constituencies that could be related to and addressed. In this sense, newspapers form an important tool for analysing the political agency of nineteenth-century monarchs in general and William I in particular, because they became such important carriers of cultural meaning that went far beyond specific political decisions. As such they crafted a particular form of political influence based on dominating popular perception that a cultural approach to political history can reveal.

Primary sources

Frankfurter Zeitung, 17 October 1880.

Kölnische Zeitung, 15 October 1880.

Königlich Privilegirte Berlinische Zeitung von Staats- und Gelehrten Sachen. Vossische Zeitung, 9 September 1876.

Neue Preußische Zeitung / Kreuzzeitung, 17 September 1882.

Secondary literature

Biefang, Andreas, Die andere Seite der Macht. Reichstag und Öffentlichkeit im >>System Bismarck<< 1871-1890 (Düsseldorf 2009).

Biefang, Andreas, Michael Epkenhans and Klaus Tenfelde, ‘Das politische Zeremoniell im Deutschen Kaiserreich 1870-1918. Zur Einführung’ in: Andreas Biefang, Michael Epkenhans and Klaus Tenfelde, eds., Das politische Zeremoniell im Deutschen Kaiserreich 1871-1918 (Düsseldorf 2008) 11-28.

Clark, Christopher, Iron Kingdom. The rise and downfall of Prussia, 1600-1947 (Cambridge, Massachusetts 2006).

Geisthövel, Alexa, ‘Nahbare Herrscher. Die Selbstdarstellung preußischer Monarchen in Kurorten als Form politischer Kommunikation im 19. Jahrhundert’ in: Forschung an der Universität Bielefeld 24 (2002) 32-37.

Geisthövel, Alexa, ‘Den Monarchen im Blick. Wilhelm I. in der illustrierten Familienpresse’ in: Habbo Knoch and Daniel Morat eds., Kommunikation als Beobachtung. Medienwandel und Gesellschaftsbilder 1880-1960 (Munich 2003) 59-80.

Geisthövel, Alexa, ‘Wilhelm I. am ‘historischen Eckfenster’: Zur Sichtbarkeit des Monarchen in der zweiten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts’ in: Jan Andres, Alexa Geisthövel and Matthias Schwengelbeck eds., Die Sinnlichkeit der Macht. Herrschaft und Representation seit der Frühen Neuzeit (Frankfurt am Main 2005) 163-185.

Stollberg-Rilinger, Barbara, ‘Was heißt Kulturgeschichte des Politischen?’ in: Barbara Stollberg-Rilinger ed., Was heißt Kulturgeschichte des Politischen? (Berlin 2005) 9-24.

Schwengelbeck, Matthias, ‘Monarchische Herrschaftsrepräsentationen zwischen Konsens und Konflikt: Zum Wandel des Huldigings- und Inthronisationszeremoniells im 19. Jahrhundert’ in: Jan Andres, Alexa Geisthövel and Matthias Schwengelbeck eds., Die Sinnlichkeit der Macht. Herrschaft und Representation seit der Frühen Neuzeit (Frankfurt am Main 2005) 123-162.

Vogel, Jakob, ‘Rituals of the ‘Nations in Arms’: military festivals in Germany and France, 1871-1914’ in: Karin Friedrich ed., Festive culture in Germany and Europe from the sixteenth to the twentieth century (Lewiston 2000) 245-264.

Herr Frederik Frank Sterkenburgh, The University of Warwick, war im Rahmen des Stipendienprogramms der Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz im Jahr 2016 als Stipendiat an der Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin. Forschungsprojekt:„Monarchical rule and political culture in Imperial Germany: the reign of William I, 1870 – 1888“

Werkstattgespräch zu Wilhelm I. am 21. 6. 2016

CC BY-SA-NB

CC BY-SA-NB

https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/mark/1.0/

https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/mark/1.0/

bpk Nr 00078894

bpk Nr 00078894

Ihr Kommentar

An Diskussion beteiligen?Hinterlassen Sie uns einen Kommentar!