Rethinking Empire in Nicholas II’s Russia: The Victimized Heartland

Gastbeitrag von Dr. Stanisław Boridczenko

Two Visions

The expansionist nature of colonial empires ignited debates among intellectual elites long before their decline in the mid‑20th century. The Russian intelligentsia under Nicholas II was no exception, delving deeply into efforts to interpret and define the essence of their homeland and its imperial identity.

Traditionally, the Romanov state, like its European counterparts, was celebrated in official discourse and by the pro-government intelligentsia as a symbol of progress. Expansion was portrayed as a moral duty, with vast territorial acquisitions – such as Central Asia, the Far East, Poland, Finland, Lithuania, and Georgia – framed as essential for Russia’s prosperity and security. This narrative linked territorial expansion with Russia’s identity and destiny, where questioning imperial ambitions was seen as challenging the nation’s fundamental mission.

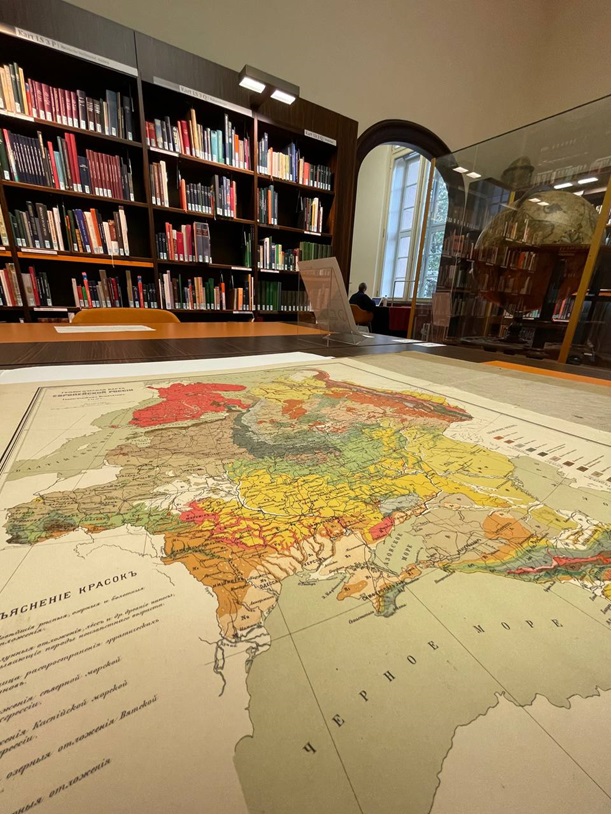

The map of the Russian Empire (here: 4°Kart. GfE Z 894‑N.S.,77) was one of the few mandatory items in every school. Its vast expanse was intended to inspire a sense of pride and loyalty among pupils. Photo from the Maps reading room in the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin.- Photo: St. Boridczenko, © CC BY-NC-SA

However, from the outset, this glorified vision of empire faced criticism from subjugated nations and anti-government intelligentsia. They emphasized the exploitation of conquered peoples and the violence inherent in maintaining imperial rule. Critics argued that the perspective of these oppressed communities, who saw Russians as conquerors and tyrants, needed to be acknowledged. For them, the empire’s grandeur was overshadowed by its inherent inequality, benefiting only one dominant nation at the expense of others.

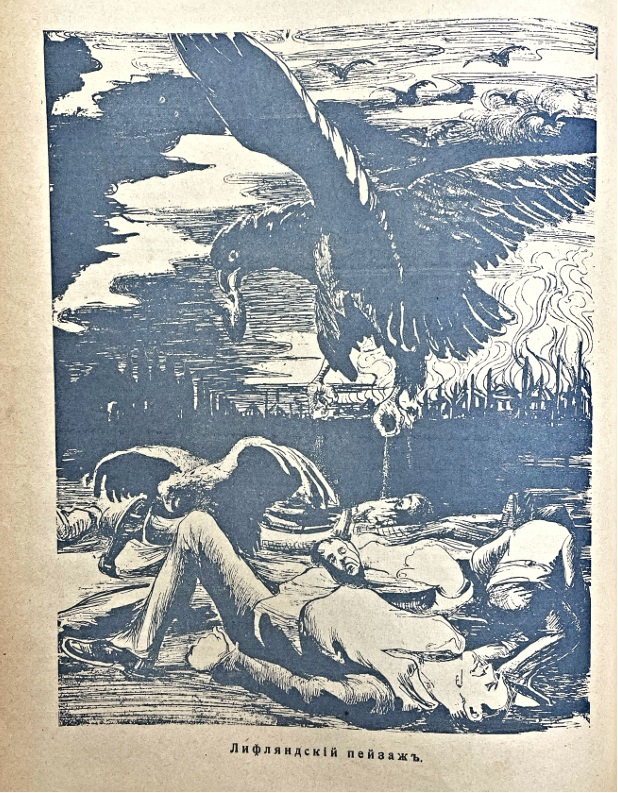

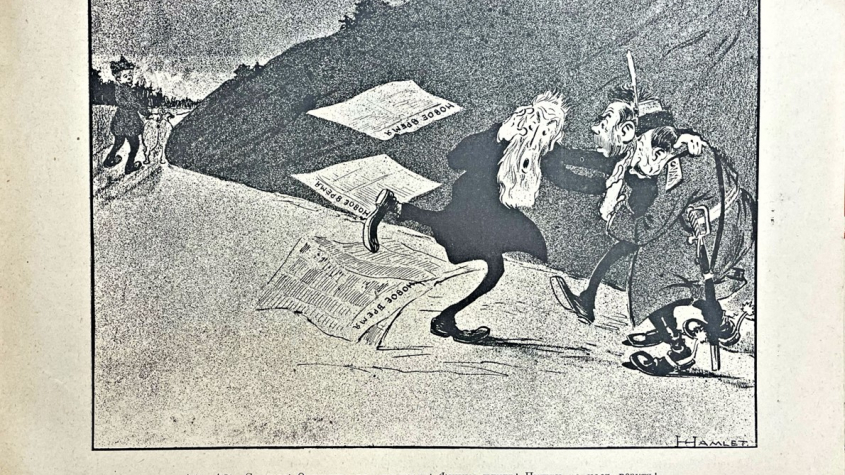

The unrest of the 1905 Revolution resonated strongly in the anti-government press, which condemned the executions carried out by the Russian army and the Cossacks in the empire’s outskirts. This illustration from Букет – нет розы без шипов № 2 (1906), p. 4 depicts the imperial repression in the province of Livonia, highlighting the brutality of these actions. – SBB-PK: 2°Ue 6783/28‑7

The Empire’s Core as Victim

The two opposing visions of empire as a beacon of progress or as an oppressor are well established and continue to influence debates to this day. However, within Russian intellectual tradition, a third interpretation holds significant weight: the view that imperial overreach primarily oppressed its own core. During Nicholas II’s reign, this perspective gained prominence, emphasizing the burdens placed on Russia’s heartland by its own status.

This alternative narrative challenged the traditional view of the imperial core as the primary beneficiary of empire. Instead, it argued that expansion drained and destabilized “true Russia”, casting the imperial core as the principal victim of imperial policies.

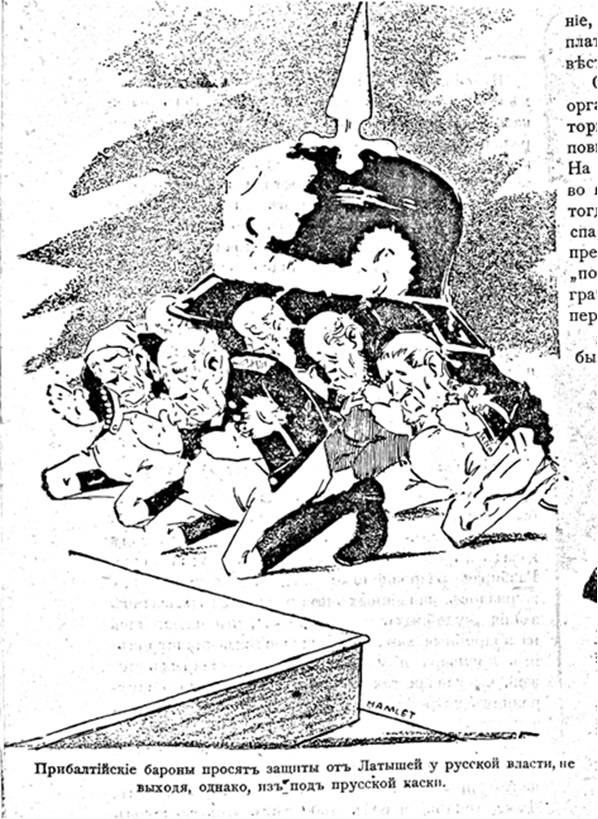

The caricature in Волшебный фонарь № 4 (1905), p. 10 criticizes the German population of the Baltic provinces, portraying Baltic Germans appealing for Russian intercession in their conflicts with Latvians. They are depicted as loyal to Russian rule only when it served their interests, while remaining strongly influenced by Prussia rather than Russia. – SBB-PK: 2°Ue 6783/28‑2

Voices of Dissent

Prominent Russian intellectuals voiced this sentiment. Among them was Fyodor Dostoevsky, whose observations in Дневник писателя from 1881 underscored the marginalization of ethnic Russians within their own empire. He lamented:

“Russia is ruled by ‘corporations.’ Germans, Poles, Jews are ‘corporations’ that help themselves. There is no corporation for Russians only; they stand alone, divided […] All the rights of the Russian man are denied.”

(cf Russian source: SBB‑PK: 29 MA 7922‑26, p. 10 ; all translations mine, S.B.)

Journalist and influential publisher Aleksey Suvorin echoed similar concerns in 1903, writing:

“Our core [Russia] has been weakening since the 18th century. Everything that could be taken from it was taken – money, troops, intellectuals – and almost nothing was returned […] Poor Russian villages remain absolutely the same as during Tsar Aleksey Mikhailovich.”

(cf Russian source: SBB‑PK: 3 A 248838, p. 253)

These critiques painted a stark picture of an imperial heartland burdened by the very nations it had conquered. Such sentiments were widely reflected in the press and literature of Nicholas II’s era, exposing deep anxieties about the empire’s cost to Russia itself.

Economic Disparities

This narrative extended beyond the aforementioned abstract concerns to specific critiques of tangible realities, such as economic inequality. Thinkers like the controversial Russian philosopher Vasily Rozanov drew sharp contrasts between the impoverished Russian heartland and the thriving imperial peripheries. In 1896, he vividly captured this disparity:

“There is nothing more striking than the impression experienced involuntarily by anyone who comes from central Russia to the outskirts: it seems that from an old, neglected, wild garden one enters a carefully cultivated greenhouse.”

(cf Russian source: SBB‑PK: 3 A 248838, p. 253)

This metaphor of a “neglected garden” symbolized the growing frustration among Russian intellectuals, who believed the heartland was being neglected to sustain once-conquered, non-Russian territories. Even members of the imperial bureaucracy shared this sentiment. In the early 1870s, Alexey Pushkarev, head of the Baku treasury chamber, condemned the financial inequities in a report on the Transcaucasus provinces:

“The incomparably richest inhabitants of the Transcaucasian region, in comparison with Novgorod or Pskov provinces, whose inhabitants eat bread with chaff, pay four times less, while the hungry man of the northern provinces [i.e., Russia] is obliged to pay for the rich inhabitants of the Transcaucasus.”

(cf Russian source: Е.А. Правилова, Финансы империи. Деньги и власть в политике России на национальных окраинах, 1801-1917. Moscow: Новое издательство, 2006, p. 265)

These subtle yet pervasive disparities undermined the traditional imperial narrative, reframing the Russian core as a victim rather than a beneficiary of expansionist policies.

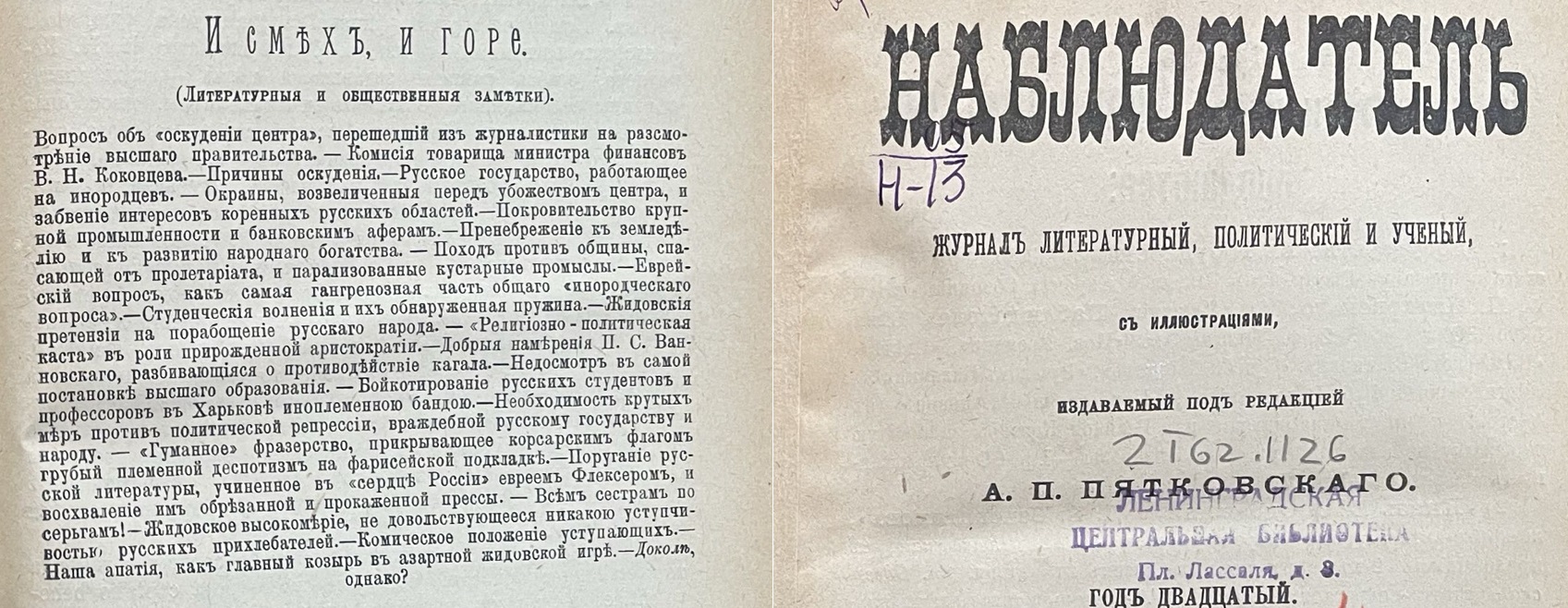

The table of contents of the literary magazine Наблюдатель № 12 (1901) highlights the central topic of the entire issue – the question of Russia’s depletion due to imperial policies that prioritized the needs of the national peripheries. The coverage of the Jewish efforts to colonize Russia appears to be an added element, serving as a sort of bonus to the main theme. – SBB-PK: Ad 4763<a>

The “Alien Stream” Flooding Russian Lands

Beyond economic concerns, the struggles of the heartland due to the imperial expansion affected nearly every aspect of life. One of the most vivid issues was the perception of colonial waves from subjugated societies encroaching on Russian lands. Southern Russia, “liberated from the Muslim yoke,” was viewed by Russian intelligentsia as being “colonized” by Armenians and Georgians. Similar fears emerged in the Asian territories of the empire, where the so-called “Yellow Peril” was seen as a threat to Russian dominance. In the Baltic provinces, Malorossia, and Bessarabia, Germans were accused of thriving at the expense of Russians, who had bled to conquer and secure these regions. In Western Russia and Siberia, Polish settlers were seen as an alien force attempting to „polonize“ everything, while Jews were often blamed for a quiet takeover of Russian cities.

A 1909 report by the secretary of the Moscow branch of the Union of the Russian People described Siberia as follows:

“The abundance of Poles at Chita station amazed us – Polish rebellious language everywhere, as if we had come to the Polish kingdom. From Chita we went to Verkhneudinsk. It is an interesting rail station: all employees are Poles, one German, and just two Russians. In the town, there are two Russian shops; the rest belong to the Jews.”

(cf Russian source: SBB‑PK: Uf 159/1310, p. 152)

Such narratives deepened the divide between the imperial government and its heartland, fueling accusations that the empire created ideal conditions for subjugated peoples, forgetting the core nation.

Implications for Modern Russian Identity

This alternative interpretation of imperial dynamics, which can be simplistically referred to as “reverse colonialism,” did not disappear with the fall of the Russian Empire. It was not an anomaly unique to Nicholas II’s Russia. Soviet policies, including affirmative action for minority groups, arguably intensified these sentiments among the wider population. Even today, echoes of this narrative of self-victimization continue to resonate in Russian political rhetoric and popular culture.

The image of “starving Russia,” a breadbasket exploited by others, remains a powerful symbol in interpretations of the Soviet past. Claims that Russians were the primary victims of an unjust system resonate nowadays across Russian society, from political and intellectual elites to ordinary people.

Numerous infographics and maps circulating on the Russian segment of the Internet symbolize this phenomenon. They emphasize the perceived exploitation of the RSFSR by other Soviet republics. The image displays search results related to this issue. – Source: http://surl.li/bvfnwj (18.12.2024)

What underscores the Russian tradition of self-victimization in interpreting its imperial past and present is the acknowledgment of the empire’s complexities. An empire can be perceived in many ways, and the perspective of the empire-building nation often differs significantly from the narrative promoted by state-sponsored discourse. Within this framework, the concept of reverse colonialism – reflected in Nicholas II’s intelligentsia discourse – reveals how unchecked imperial ambitions can erode the foundations of power, leaving behind a legacy of division and resentment.

Herr Dr. Stanisław Boridczenko, Uniwersytet Szczeciński, war im Rahmen des Stipendienprogramms der Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz im Jahr 2024 als Stipendiat an der Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin. Forschungsprojekt: „Do we need any colonies at all? Different ways of perception of the Russian imperialist status by the Russian intelligentsia in the Russian empire of Nicholas II (1894–1917)“

Online-Vortrag am 21. 11. 2024

CC BY-SA-NC 3.0

CC BY-SA-NC 3.0

Lizenz: CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Lizenz: CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

SBB-PK CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

SBB-PK CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 SBB-PK CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

SBB-PK CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

Ihr Kommentar

An Diskussion beteiligen?Hinterlassen Sie uns einen Kommentar!