With Nabokov in Berlin

Gastbeitrag von Prof. Zsuzsa Hetényi, Loránd-Eötvös-Universität Budapest

After my arrival at the Stabi, I started by a thorough “obkhod” (going around) of the wonderful retro-modern building of the library for choosing and noting the coziest places for reading at different times of the day, for scanning, for taking photos of the pages, for eating, for cold days and for warmer days (of my mostly golden-sunny October-November stay).

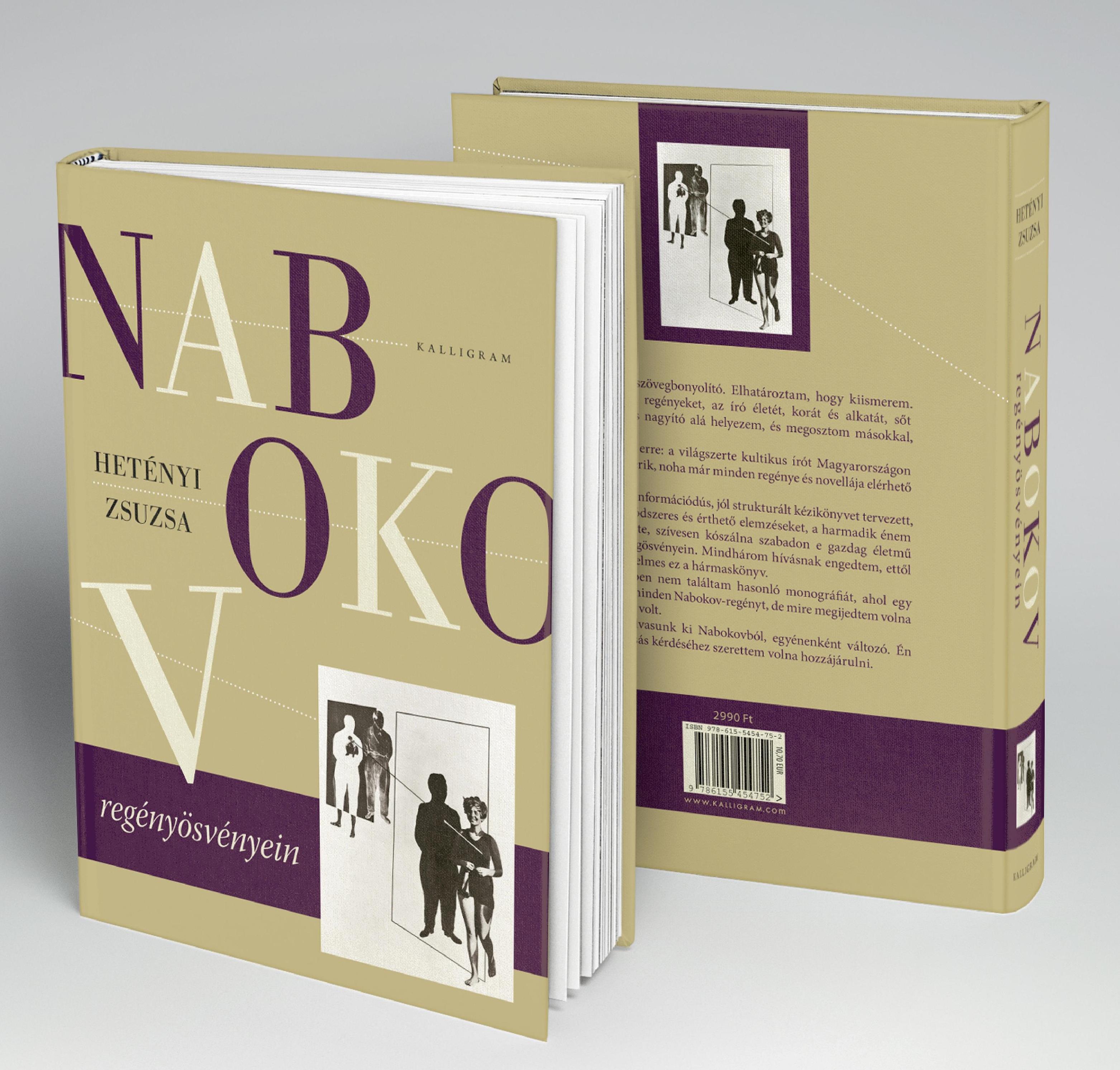

I applied for the fellowship and arrived in Berlin for preparing a monograph on Vladimir Nabokov in English. This book would be my second one on Nabokov, the first one being in Hungarian, a small language with a narrow reading audience. Now I see a kind of omen in the fact that on the cover of my Hungarian book I put a László Moholy-Nagy montage made in 1926 in Berlin.

A Hungarian scholar has many hindrances when aiming to gain a place in a specific field’s scholarly community: besides the small language in the country we have libraries with a very limited budget, and also with a somewhat narrow-minded strategy of purchase. Vladimir Nabokov was a Russian-born writer whose family was forced to leave Russia (because of the revolution of 1917), and went to Europe. Then, already with his own son born in Berlin, he left for the USA, where he started writing in English and became a famous American bestseller writer thanks to his Lolita. Then another move – he returned to Europe, he died in Montreux, Switzerland in 1977. His life was marked by many transitions, but in Berlin he spent the longest period of his life.

Soviet censorship had an absolute power in Socialist Hungary until its very end, so an official permission was obligatory for everything. Only that what could be printed in the USSR could be published in Hungary, so Nabokov was prohibited in both places until the late glasnost’ era, until 1987. Hence the paradoxical situation: Hungarian readers started to read Nabokov only a decade after his death, around 1989, when the Soviet censorship was abolished. This is why the Hungarian reading public became somewhat little attuned to Nabokov and this is why Nabokov is not at all on the place which he deserves and owns in world literature, he is only starting his way towards the Hungarian hearts and minds. So a Hungarian librarian will not order books on him, especially not waste the little budget for purchasing a book in English about a Russian writer or in Russian about an American writer. That is why a Hungarian scholar in order to be up-to-date in his or her field has to travel every 5-8 years and go to other big libraries of richer countries with a wider scope of interest.

I am sure of being not the only scholar who, during an intensive reading period, is faced the basic dilemma of the humanities in the postmodern era: the growing number of publications, the obligation to know everything and — a most difficult task — despite the huge burden of secondary reading keeping the creative power to write about one’s own ideas, without losing the pleasure of reading and analyzing the primary text. The biggest good surprises can happen coming across exciting ideas of others and the biggest bitter surprises when finding one’s own ideas already written by someone else earlier.

My four-week stay at Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin was a mixture of intellectual pleasure, hard work and some tension due to the short time and a lot of events, partly planned before, partly unforeseen earlier. Sometimes I left for events or exhibitions during the day – I am convinced that a grant’s successfulness can be measured also by new impressions and information about the city, the country and its history and culture.

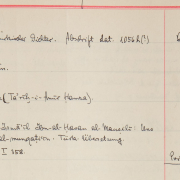

I wonder how many books one has to read before writing another book… I asked myself this unanswerable question many times while comparing the amount of books to be read with those already read and my time frame, four weeks of my fellowship. Depending on the search criteria, my narrow field of interest connected to my nearest research goals (Vladimir Nabokov) gave from 189 up to 480 results only in category of books, apart from journal articles. Among them there were about a hundred from recent years and many older ones which I could not find even in US-based libraries. The great difference from American libraries is a result of the purchasing strategy: Stabi keeps an eye equally on the French, Russian and any-language scholarly book-market and purchases according to the subject, not language, publisher or country. So I could find very small but useful editions from the Urals or Central Asia, and also publications from small local institutes in France. Finally, I ordered approximately 90 books – some of them were read partly only, and many were photographed: I have returned to Budapest with about 500 double-page photos, some of them taken in the Rara Collection at Unter den Linden building (with special permission, of course). There, in one of the small journals looking very trendy and not serious, I have discovered a photo taken in 1926 at the rehearsal of a humorous play for the annual Russian ball, with a very young Nabokov sitting first on the left:

Russkii Berlin 1927.2. Actors of the theater piece „Kvatch“ to be presented at the Russian Ball in 1927. Nabokov sits first from the left. He is mentioned in the list under his pen name V. V. Sirin he used in Berlin. – Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin. Signatur: 4° Td 2045 R

I was amazed when getting acquainted with Slavistik-Portal, this very professional hub of information about everything possible, including events, news and scientific novelties. With a great regret I left its scrutinizing for later times as I had realized I will be able to do it from home, and I treasured my Berlin-time for things feasible only on the spot.

I visited the library nearly every day of my Berlin stay, the longest day being from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m., when I came first and left last… After a day like that one feels very far from the real world. And in the nights I copied my notes and photos to different memory cards and virtual libraries. I remember one night reading the word “Abholbereit” on the library-“Zettel” as follows: Alcoholbereit… (NB. I am abstinent… Still, I brought home a little “Berliner Luft” bottle given to me as a farewell present from Sabine Kaiser from the Eastern Europe Department, who was my universal helping librarian angel during all my stay.)

I made research not only on my goal stated in my application (Nabokov during his Berlin period) but for many further chapters, and also for my public lecture held November 12 under the title: “…doves and lilies, and velvet…” – Translating self-translation with remarks on synaesthesia and bilingualism (the case of Nabokov). The beauty of translating self-translating authors to a third language is that we have two originals in our hands. My proposition was to make a hybrid text out of the two and always use the more poeticized one – this is how I worked when translating Nabokov’s Mary/Mashenka and Glory/Podvig into Hungarian.

As for my future book, I worked hard on the problem of influence of Symbolist Andrey Belyi (1880–1934) on Nabokov. First of all, we have to ask what means influence in literature. Influence is the driver of literary evolution. It is not copying, not repetition, not being a disciple, but also contradicting, varying the answers to some problems raised by the elder generation, and – what interested me most – parodying. Already in 1921 Yury Tynianov argued that early Dostoevsky parodied Gogol’s works. Parody is also a postmodern phenomenon as one form of intertextuality. A further study I planned to elaborate in Berlin was Nabokov’s letter-coding, that is, his special device of attributing different meanings to individual letters of the alphabet in accordance with their graphic form. As a simple example, one of his heroes waiting for his execution associates the Russian Г (G, identical to Greek gamma) with a scaffold and Y with a catapult. Nabokov was a synesthete, so he associated also colors and images with letters. As he writes in his memoirs, Speak, Memory!:

“The long a of the English alphabet (and it is this alphabet I have in mind farther on unless otherwise stated) has for me the tint of weathered wood, but a French a evokes polished ebony. This black group also includes hard g (vulcanized rubber) and r (a sooty rag being ripped). Oatmeal n, noodle-limp l, and the ivory-backed hand mirror of o take care of the whites. I am puzzled by my French on which I see as the brimming tension-surface of alcohol in a small glass. Passing on to the blue group, there is steely x, thundercloud z, and huckleberry k. Since a subtle interaction exists between sound and shape, I see q as browner than k, while s is not the light blue of c, but a curious mixture of azure and mother-of-pearl. Adjacent tints do not merge, and diphthongs do not have special colors of their own, unless represented by a single character in some other language (thus the fluffy-gray, three-stemmed Russian letter that stands for sh, a letter as old as the rushes of the Nile, influences its English representation).

I hasten to complete my list before I am interrupted. In the green group, there are alder-leaf f, the unripe apple of p, and pistachio t. Dull green, combined somehow with violet, is the best I can do for w. The yellows comprise various e’s and i’s, creamy d, bright-golden y, and u whose alphabetical value I can express only by ‘brassy with an olive sheen.’ In the brown group, there are the rich rubbery tone of soft g, paler j, and the drab shoelace of h. Finally, among the reds, b has the tone called burnt sienna by painters, m is a fold of pink flannel…”

A third problem to check was Nabokov’s relationship to the German language and culture, which he denied. He said he had not been involved in the social life in Berlin and did not learn and speak German. It is a mystification – he knew German well enough to read German newspapers and also to translate some poems, and was involved in many Russian cultural events in Berlin from giving lectures to playing in a small private theatre-group. He loved Berlin’s museums, the Zoo, strolling about in the streets, and also tennis courts… (as his favorite one, hidden behind the Schaubühne, is abandoned and closed and starts to decompose, I had to climb the fences to get in for a photo…)

So-called “Nabokov-places” are wonderfully listed and placed on a map in Dieter Zimmer’s Nabokovs Berlin (Nikolai, 2001) on the pages 142‑143.

During my stay I met several colleagues and fellow translators, and also visited places and museums (the new Pergamon Panorama before its opening), attended events on Russian culture (e.g. in the Literarisches Colloquium Berlin in Wannsee about the German translation of The Master and Margarita and as many commemorations about German history as I could (Reichstag, Gurlitt exhibition, Topography of Terror). I have never heard before about the fact what a coincidental day November 9 is in German history. My Facebook post on the Pogrom book presentation in the Akademie der Künste and the speech of Mr Frank-Walter Steinmeier got nearly 200 likes – I was happy to bring closer not only this part of German history but especially the culture of remembrance in Germany to some of the Hungarian intellectuals.

I have to return once (or more times?) again.

Frau Prof. Zsuzsa Hetényi, Loránd-Eötvös-Universität Budapest, war im Rahmen des Stipendienprogramms der Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz im Jahr 2018 als Stipendiatin an der Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin. Forschungsprojekt: „A monograph on Nabokov in English“

CC-BY-NC-SA

CC-BY-NC-SA

Foto: SBB-PK / CC BY-NC-SA

Foto: SBB-PK / CC BY-NC-SA

. Photo: Ⓒ Linn Ahlgren/Nationalmuseum

. Photo: Ⓒ Linn Ahlgren/Nationalmuseum

SBB-PK CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

SBB-PK CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

Ihr Kommentar

An Diskussion beteiligen?Hinterlassen Sie uns einen Kommentar!