Rewriting the Gem: Revolution and Devolution in Zecharia ha-Rofé’s Al-Durra al-Muntakhaba

Gastbeitrag von Dr. Ariel Malachi

Introduction

Zecharia ha-Rofé, a member of the Jewish community in Dhamar, Yemen, was one of the most important intellectual figures of the first half of the 15th century. His body of work reflects a unique blend of rabbinic tradition and philosophical inquiry, shaped by both Jewish and Islamic intellectual currents.

Among his better-known contributions are Midrash ha-Ḥefetz, a philosophical midrash; al-Wajīz, a medical treatise; and commentaries on Maimonides’ Mishneh Torah and Guide of the Perplexed. Al-Durra al-Muntakhaba, however, stands out for its creative use of allegory to elaborate on themes only briefly touched upon in Midrash ha-Ḥefetz. It is a complementary and interpretive endeavor, using narrative symbolism to explore deeper philosophical ideas. Yet al-Durra isn’t just a forgotten allegorical text. Its seems to be a key to understanding how Jewish thinkers in medieval Yemen wrestled with philosophy, faith, and interpretation.

A Tale of Two Texts

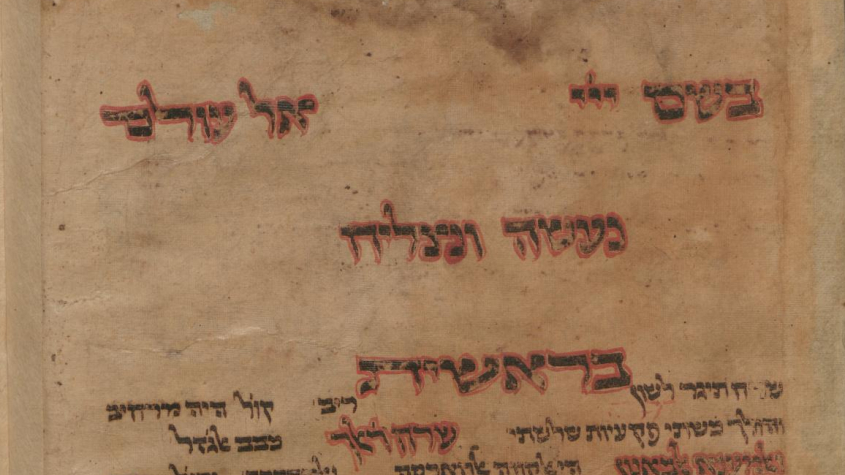

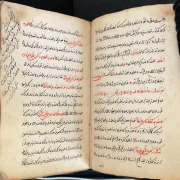

Intriguingly, al-Durra has survived in at least two markedly different versions. A shorter one is found in a well-preserved manuscript in London (Or. 2746), while a longer version resides here in Berlin (Qu.554). Normally, in manuscript cultures like that of Yemenite Jewry, longer texts emerge as expansions of earlier, more concise originals. But in this case, the opposite seems to be true.

Textual comparison suggests that the shorter London version was composed later—not as a simple summary, but as a selectively edited text, omitting paragraph after paragraph from the longer, earlier version. This raises some pressing questions: why did Zecharia trim and modify his earlier work? Is it possible that Zecharia engaged in self-censorship, omitting various paragraphs for reasons other than literary ones? Does this censorship have anything to do with the allegorical debate in Yemen?

The Debate over Allegory in Yemen

The issue of allegorical interpretation was far from merely academic in medieval Yemen. We have evidence that at least from the 14th to the 15th centuries, Yemenite Jewish thinkers fiercely debated the limits and legitimacy of philosophical, non-literal readings of sacred texts.

The extreme allegorism of some thinkers was radical in at least three respects:

(a) The type of text: Their allegorical interpretations extended not only to midrashic texts—traditionally more flexible in interpretation—but also to the Torah itself.

(b) The content of the text: Within this philosophical-allegorical framework, not only miraculous stories and unrealistic descriptions were read non-literally, but also concrete figures such as Moses and Aaron, and even commandments, were understood allegorically.

(c) The scope of the text: This was not a localized or selective practice, but a comprehensive, systematic effort to assign a non-literal allegorical layer to every detail in the biblical text—without exception—including all narratives, characters, and commandments.

Was Zecharia an Extreme Allegorist?

Zecharia’s own introduction to Midrash ha-Ḥefetz outlines cautious criteria for such exegesis, emphasizing moderation and restraint—positioning him as a moderate allegorist.

Yet in Al-Durra, especially in the Berlin version, he appears to push those boundaries to an extreme. In this version, allegory is the dominant mode of argument—layered, rich, and seemingly unbounded.

Was this boundless allegorism later tempered in the revised, shorter London version? If so, the evolution of the text becomes not just a literary question, but a window into a deeper intellectual and theological shift.

Method and Goals

To investigate this development, the research project pursues several goals:

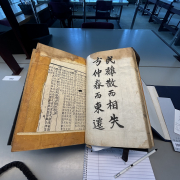

- To produce a full transcription of both the short and long versions of Al-Durra.

- To analyze the changes between the versions in terms of style, content, and philosophical outlook.

- To assess how these changes relate to Zecharia’s stated hermeneutical principles.

- To better understand Zecharia’s place in the broader debate about allegory in Yemenite Jewish thought.

Al-Durra

Working with Fragile Texts

The Berlin manuscript—likely the most complete long version of Al-Durra—has suffered significant water damage. While the digital scan is mostly legible, many crucial passages could only be deciphered through direct examination. My time at the Staatsbibliothek allowed for just that.

Thanks to the supportive environment of the library and the accessibility of its rare materials, I was able to consult most of the long version and begin comparing it to the London manuscript.

Preliminary Findings

My time at the library was primarily devoted to transcribing the Berlin manuscript, comparing it to the London manuscript, and identifying key differences. A preliminary observation confirms that beyond literary modifications, the longer Berlin version reflects a more extreme allegorical approach to scripture, while the later London version aligns more closely with the moderate hermeneutics Zecharia outlines in the introduction to Midrash ha-Ḥefetz.

From this, we may conclude that Zecharia began as a radical allegorist but later revised his stance, adopting a more restrained interpretive method. This transformation sheds light not only on Zecharia’s intellectual development but also allows us to reexamine and reappreciate his broader contribution.

Why It Matters

Identifying intellectual shifts in philosophical works like Al-Durra helps us grasp the nuances of scholarly life far from the centers of medieval Europe. Zecharia’s blending of Jewish sources with Islamic philosophical modes reflects the dynamic cultural world of Yemenite Jewry. His struggle with allegory echoes broader tensions in religious thought—tensions that still resonate today.

By uncovering the textual layers of Al-Durra, we are not just restoring a manuscript. We are recovering a moment of courageous intellectual exploration—and perhaps also of quiet self-revision—revealing Zecharia’s hidden, long-neglected legacy.

Dr. Ariel Malachi, Bar-Ilan University, war im Rahmen des Stipendienprogramms der Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz im Jahr 2025 als Stipendiat an der Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin. Forschungsprojekt: „Al-Durra al-Muntakhaba (The Chosen Gem) and its Versions: From Text to Method“

Public Domain Mark 1.0

Public Domain Mark 1.0

Photo: Lukáš Kubík

Photo: Lukáš Kubík Public Domain

Public Domain Public Domain

Public Domain

CC-BY-NC-SA 3.0

CC-BY-NC-SA 3.0

Ihr Kommentar

An Diskussion beteiligen?Hinterlassen Sie uns einen Kommentar!