Studying Rome’s Earliest Printers at the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin

Gastbeitrag von Elena Fogolin

In March 2025, I had the opportunity to spend a month conducting research in Berlin, supported by a research grant from the Staatsbibliothek aimed at advancing my study of German printers active in Rome in the 1470s and 1480s. This stay formed a core component of my wider project on early printing in Rome, early printing techniques and their development, as well as on the circulation of early printed books, in the light of an uncertain commercial and technological progress.

In 15th-century Rome there was a clear dominance of German printers, while Italians rather played the role of financiers, publishers and editors. The printers were German and many of their buyers as well, considering that Rome attracted numerous visitors and pilgrims in general, and German in particular. Moreover, in Rome there was the presence of a German community, which might certainly have helped the newcomers to adapt to the new city, as well as to a book market, of which they did not have an adequate knowledge. Considering the instability of numerous enterprises, the mobility of printers between different shops, the exchange of punches, matrices or cast type, of typographical materials in general, and the absence of dates and references to the printer in several editions, it is difficult, if not impossible, to quantify the actual number of printing establishments that existed in Rome.

My project addresses these gaps by examining, on the one hand, provenance evidence in incunabula – bindings, manuscript annotations, decoration, ownership inscriptions, purchase notes, and related features – to reconstruct their circulation and use, and, on the other hand, considering the book as an edition: its production method, and several bibliographical aspects that up to now have not been systematically investigated.

Before my stay in Berlin, I had examined 449 copies belonging to 350 editions; during the month spent at the Staatsbibliothek, I consulted 60 further copies representing 59 editions. This group comprised 51 copies of 50 editions I had not previously seen, and 9 additional copies of editions which I had already studied. As a result, my sample now includes 509 copies of 409 editions. The Staatsbibliothek holdings proved exceptionally rich as it preserves extensive collections that include volumes originating from ecclesiastical libraries, noble households, private scholarly collections, and 19th-century acquisitions from across Europe. This diversity allowed for the reconstruction of complex provenance histories and offered insight into how Roman editions travelled across social and geographic contexts.

Among the volumes examined, several copies captured my attention through their distinctive provenance features.

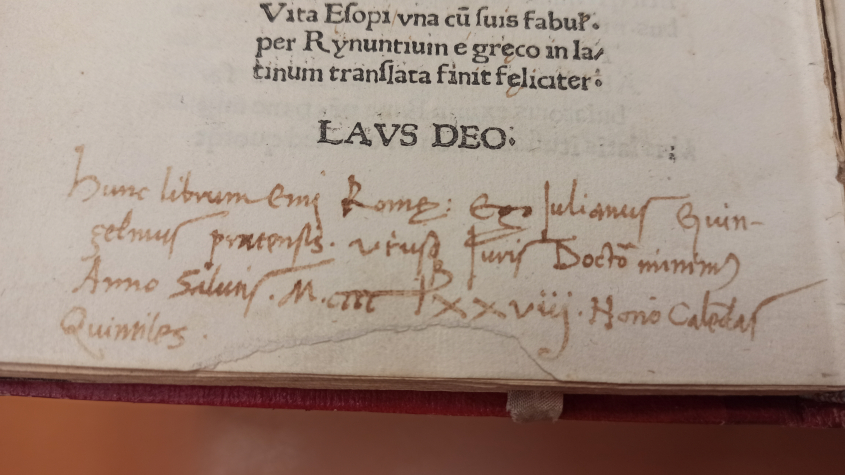

One remarkable example is an edition of Aesop’s Vita et Fabulae (8° Inc 3393), a quarto edition on Chancery sheets printed in Rome around 1475 by Bartholomaeus Guldinbeck or Wendelinus de Wila (GW 336, ISTC ia00099500). The copy is bound in early 19th-century red leather with gilt tooling, yet its earliest recorded owner takes us back to the 15th century. The jurist Giuliano Guizzelmi of Prato acquired the book in Rome in 1478, leaving an explicit purchase note that precisely records the date and place of acquisition. The volume bears extensive manuscript annotations by Guizzelmi, consisting of keyword extraction, reading marks, manicules, revealing his active engagement with the text. On the last leaf, a long inscription dated 24 October 1505 attests that he completed reading and annotating the volume. This kind of evidence of use offers rare insight into the scholarly practices of early Roman book owners. The subsequent history of the same volume further testifies to the mobility of early printed books. In the late 18th and early 19th century, the copy belonged to Count Dimitrij Petrovich Boutourlin, a Russian diplomat and bibliophile whose first library, located in Moscow, was destroyed in 1812. He later rebuilt his collection, which became well-known among bibliophiles and was catalogued and sold in multiple auctions. His armorial bookplate is found on the front pastedown. The volume later entered the Royal Library in Berlin. This layered provenance – a 15th-century Italian jurist to a Russian aristocratic library, and finally to a major European institution – captures the transnational trajectories that incunabula frequently followed.

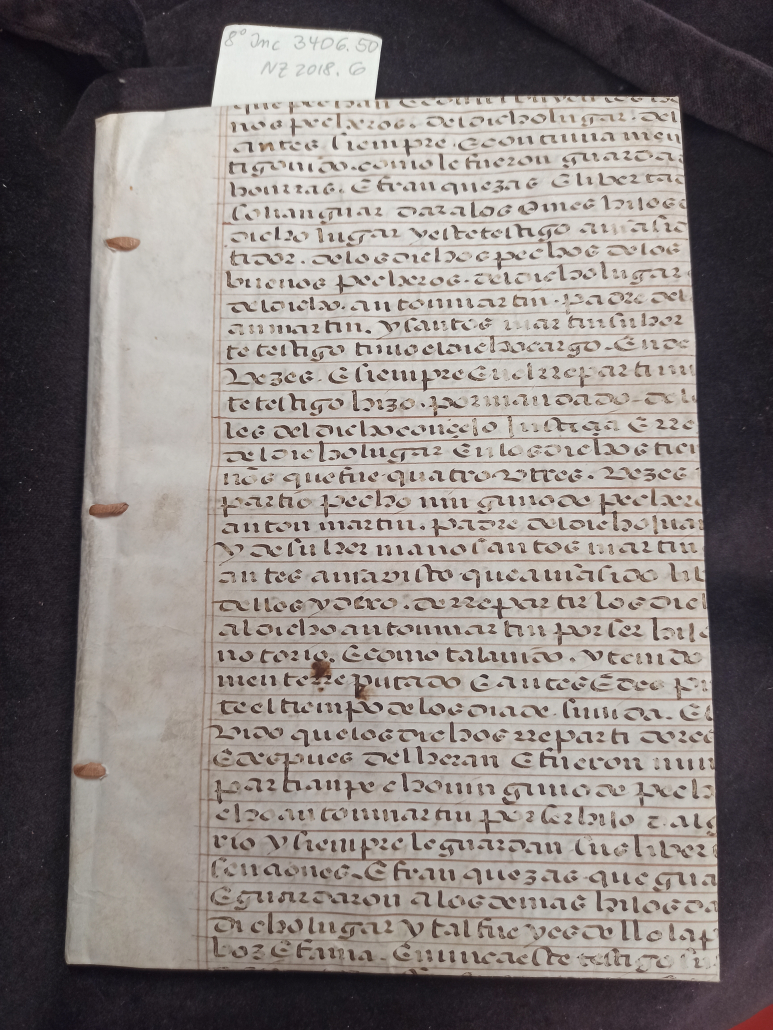

Binding made of parchment manuscript waste containing a late medieval Spanish legal text. Berlin, Staatsbibliothek, 8° Inc 3406.50 = NZ 2018.6

Another noteworthy example is a copy of Aeneas Silvius Piccolomini’s De duobus amantibus Euryalo et Lucretia (8° Inc 3406.50 = NZ 2018.6), another quarto edition printed on Chancery sheets and attributed to Johannes Bulle around 1480 (GW M33503, ISTC ip00678000). The binding is made from parchment manuscript waste containing a late medieval Spanish legal text written in a formal Gothic script. The reused document concerns local fiscal administration, focusing on obligations and exemptions within a defined community. Central to the text is the distinction between pecheros – tax-paying commoners – and hijosdalgo, nobles exempt from taxation. The fragment appears to derive from a legal or administrative record addressing disputes over tax liability, as suggested by references to litigation (litigauan) and to individuals claiming status as “libres y exentos” (free and exempt). It also mentions figures involved in the practical administration of taxes, including those responsible for collecting and allocating revenue (andar pidiendo e cobrando, repartidores), as well as testimony given “by order of the council” (testigo hizo por mandado del concejo), indicating a municipal governance context. The repeated invocation of “franqueza e libertad” implies formal recognition of privileges or immunity from fiscal duties. The early inscription “Ex libris Antonij πρεσβύτερο” suggests ownership by a cleric named Antonio, while later stamps document the book’s incorporation into the Berlin collections in 2018.

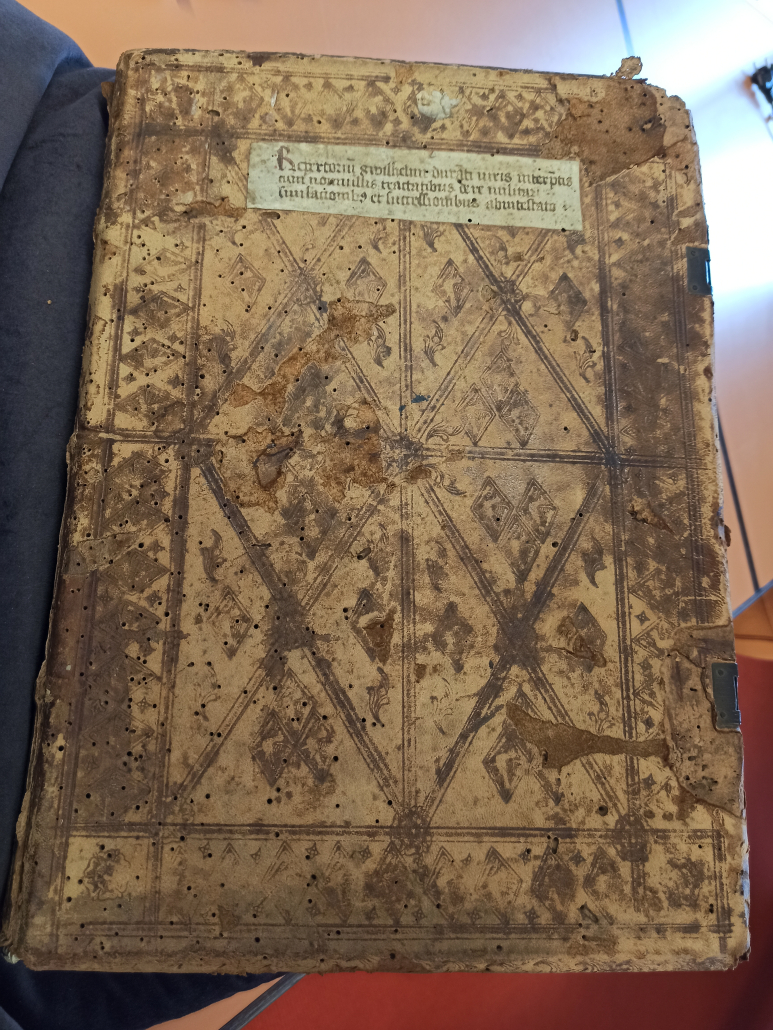

Fifteenth-century German blind-tooled pigskin over wooden boards. Berlin, Staatsbibliothek, 2° Inc 3549.

Equally fascinating was a large volume containing Bartholomaeus Cepolla’s De simulatione contractuum (Inc 3357 an 2° Inc 3549), a folio edition on Royal sheets dated 1 September 1474 likely “In domo Antonii et Raphaelis de Vulterris” (GW 6505, ISTC ic00397000) bound together with two other legal works printed the same year in Rome. The binding – 15th-century German blind-tooled pigskin over wooden boards – features a geometric decorative pattern and retains structural evidence such as remnants of metal furniture. The volume provenance traces back to the cathedral library of Freising, where it formed part of the ecclesiastical collection prior to secularization in the early 19th century. Stamps of the Munich Royal Library attest to its subsequent transfer to that institution, before it ultimately entered the Berlin library, certainly sold as a duplicate from Munich. This example not only demonstrates the movement of legal incunabula across ecclesiastical and state repositories but also shows an interesting example of an early German binding.

Beyond the specific discoveries made in individual volumes, the research period underscored the enduring relevance of historical collections for reconstructing the social, intellectual, and material dynamics of early printing. The Staatsbibliothek’s staff provided invaluable assistance, facilitating access to rare materials and supporting detailed examination of the incunabula. The opportunity to work extensively with the Berlin collections has significantly advanced my project and reaffirmed that the study of early printing remains inseparable from the close analysis of surviving physical copies. Each volume preserves a unique constellation of evidence – technical, textual, and historical – that collectively enriches our understanding of the first generations of printed books and the networks that sustained their production and diffusion.

Elena Fogolin, University of Udine/Universität Mainz, war im Rahmen des Stipendienprogramms der Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz im Jahr 2025 als Stipendiatin an der Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin. Forschungsprojekt: „German printers in Rome in the 1470s-1480s: Book Output and Circulation“

CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

CC BY-NC-SA 4.0![F[riedrich] E[duard] Bilz, Das Neue Naturheilverfahren: Lehr- und Nachschlagebuch der naturgemäßen Heilweise und Gesundheitspflege, Vol. I (Leipzig: Verlag von F.E. Bilz, 1898](https://blog.sbb.berlin/wp-content/uploads/IMG_2063a-180x180.png)

Public Domain 1.0

Public Domain 1.0 akg-images / Universal Images Group / For Education Use Only

akg-images / Universal Images Group / For Education Use Only

Ihr Kommentar

An Diskussion beteiligen?Hinterlassen Sie uns einen Kommentar!