The Manuscripts Oskar Rescher Sold to the Berlin State Library 1913–1936

Gastbeitrag von Dr. Güler Doğan Averbek

Introduction

Many of the libraries in Europe and America that have Islamic manuscripts in their collections owe a significant part of them to Oskar Rescher (aka Osman Reşer, 1883–1972). He was a global trader and broker of manuscripts, deserving the title of probably the most active trader of Islamic manuscripts in the 20th century, selling them to many countries. This aspect of his has gone unnoticed. Islamic manuscripts sold by Rescher are available today in the British Library (then the British Museum), Cambridge University Library, Bodleian Library, Uppsala University Library, Basel University Library, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale, University of California Libraries, the Vatican Library, and the Austrian National Library.

Hundreds of Turkish, Arabic, and Persian manuscripts have been included in the collections of libraries in Munich, Hamburg, Leipzig, Göttingen, Tübingen, and Halle through the expertise and trade activity offered by Rescher, who had established a limited network of relations with his field between Turkey and Germany during his time in Istanbul. A significant portion of the manuscripts the Berlin State Library bought in the 20th century had been obtained through Rescher. These manuscripts are the ones Rescher gradually sold to the library between 1913 and 1936.

However, the 1,722 volumes that were sold to the State Library after Rescher’s death and had been purported to be his personal collection had nothing to do with Rescher, according to our investigations. These manuscripts were sold to the library by Ayla König (1918–1993) in 1974. We are unsure as to how the process had occurred, as all correspondence regarding this purchase has been lost.

A study published in İslam Tetkikleri Dergisi – Journal of Islamic Review 11,2 (2021): 477-568 will involve discussions about the manuscripts Rescher sold to the Berlin State Library between 1913 and 1936 after briefly touching upon his life story; the study will also present a detailed list of the manuscripts (PDF pp. 12–92). This list was created by examining the library’s acquisition journal and inventory notebooks, scanning the printed and digital catalogues, and viewing all the manuscripts that had been obtained by way of Rescher. To our knowledge, no list or inventory study regarding these manuscripts has ever been done at the library or anywhere else prior to our study.

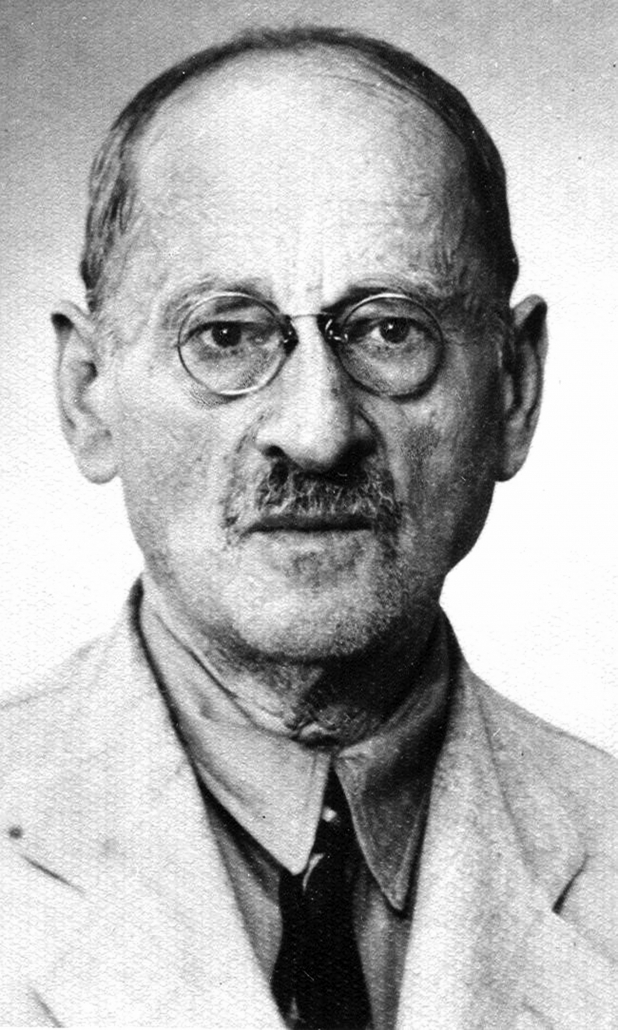

Oskar Rescher

Rescher at his 40s. – Foto: Besitz Ramazan Şeşen. Mit seiner freundlichen Genehmigung

Rescher was born on October 1, 1883 in Stuttgart as the only child of Adolf and Leopoldina; his full name was Oskar Emil Rescher. After becoming a Turkish citizen in 1937, he took the name Osman Yaşar Reşer. In addition to his mother tongue, he was fluent in Arabic, Persian, Turkish, Greek, Latin, French, Spanish, English, Russian, and Danish. He started studying law at the University of Munich in 1903; in 1905, he transferred to the Department of Oriental Languages in the Faculty of Philology at Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität zu Berlin (today Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin), from which he graduated on October 20, 1908. He received the title of doctor in 1909 and attended Leipzig University from 1909 to 1910 to finish his education.

Rescher, who had been visiting Istanbul since 1909, studied manuscripts in Istanbul and Bursa after obtaining official permission throughout these trips. Around this time, he began to publish the results of these studies as articles in many journals, as well as books that he had prepared on the basis of manuscripts in Istanbul with the particular support of İsmail Saib Efendi (1873–1940). While he prepared his works for publication, he developed him-self under the patronage of İsmail Saib Efendi with their master-disciple and in fact friendly relationship. This period ended with the outbreak of World War I, which was affecting the whole world. He was summoned to military service and within 24 hours moved to his post. He was stationed first in Montmédy, and then at the Halbmondlager POW Camp in Wünsdorf, near Berlin.

He received the title of associate professor from the University of Breslau in 1919 with his thesis titled “Studien über den Inhalt von 1001 Nacht”, which he dedicated to Carl Brockelmann (1868–1956). He became a professor in 1925.

Rescher, who had left Istanbul urgently in 1914, was able to return to this city only in 1925 at the age of 42, after the Ottoman State had disappeared from the stage of history; he spent the rest of his life on Turkish soil, mostly in Istanbul.

Rescher at his 60s. – Foto: Aus dem Besitz Nicholas Rescher. Mit seiner freundlichen Genehmigung

Having arrived in Istanbul prior to the Balkan Wars, Rescher’s journey was the beginning of a chain of events that would lead to him making Istanbul his home in the future. Rescher, who had turned to Orientalism and received the title of doctor in the field of Oriental languages after terminating his law studies in Munich, searched ways to become educated in this field and chose to settle in Istanbul. When examining his reasons for settling in Istanbul, it is necessary to question what meaning Istanbul had in the last stage of the Ottoman Empire in terms of Orientalist research and Orientalist scholars as well as what environment Rescher had encountered and what relationships formed in this city. Certainly the intellectual environment and libraries of Istanbul, which was still a center of attraction for scholarly activities in those years, played a key role in this choice.

With a decree published in the Turkish Official Gazette dated June 2, 1937, Rescher became a Turkish citizen. He held a number of positions during his years in Turkey.

His old age he spent struggling with illnesses. In his final days, he stayed at the Artigiana Old-People’s Home in the Harbiye neighborhood of Istanbul’s Şişli District. He was hospitalized on January 1, 1972 with a broken arm, enlarged prostate, and extreme exhaustion. He could no longer walk. He passed away on Sunday night, March 26, 1972 at 11:30 p.m. He is buried in Silivrikapı Cemetery. Muzaffer Ozak, Salih Tuğ, and Yusuf Ziya Kavakçı were among those who attended his funeral ceremony at Bayezid Mosque. Muzaffer Ozak, who led the funeral prayer, was also among those who lowered the deceased into his grave.

Rescher continued to work without interruption from the first article he published in 1909 until his death. As far as we could determine, throughout this period, he published 58 books, 76 articles, 68 book reviews, five book translations, and two article translations.

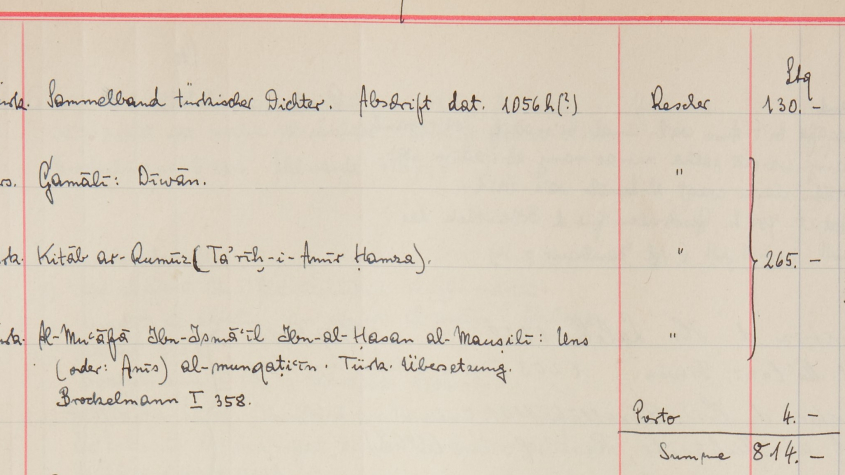

The Manuscripts Rescher Sold to the Berlin State Library

Rescher’s professional manuscript trade with the Berlin State Library (then: Prussian State Library) began in 1924. However, eight manuscripts had been added to the collection through Rescher before, between 1913 and 1914. According to us, Rescher had obtained these eight manuscripts from Istanbul and had planned his manuscript trade already at that time, but the war had intervened. After the war, he was working in Breslau, from where he started going back and forth to Istanbul in 1924; within a year he permanently left Germany and settled in Istanbul. As a result, Rescher had been an active supplier of manuscripts to the library between 1913 and 1936, procuring 1,192 manuscripts.

Rescher mostly sent the manuscripts by mail. More than half of the manuscripts he provided were in Turkish. He likely attempted to procure Turkish manuscripts on the library’s request. No correspondence exists regarding Rescher’s manuscript trade, which was in operation for 23 years.

Due to the changing conditions in Germany, Rescher’s contact with the Prussian State Library was broken off following the sale of 10 volumes of manuscripts on August 26, 1936. This was his last contact with the library until a postcard he sent to West Berlin on September 20, 1971. On this date, he offered the library the complete works of Sa‘dî‑i Şirazî, which consisted of 640 folios and contained 24 miniatures; however, the library found the price so high that it would not purchase the manuscripts. Rescher passed away in Istanbul six months after the date on the postcard.

Apart from the miscellaneous duties he performed in Ankara where he had been living for a little while and in Istanbul where he consistently resided, Rescher’s unvarying task was book trade, particularly manuscript trade. He sold the manuscripts he had selected from the second-hand bookstores to libraries and second-hand bookstores abroad at reasonable prices as if he were on a mission. The manuscripts were as uncommon as the low fees he requested. He appears to have offered manuscripts that had been carefully selected in terms of both physical features and content. Among them are lost works, unique copies of works, autographed copies, and a considerable amount of palace manuscripts. As is under-stood in recent times in particular from the ownership records and stamps on the manuscripts sold to the library, some of the manuscripts had been selected from estate sales. The manuscript market is known to have been rich at that time due to the dervish lodges and madrasas that had been closed down; manuscripts could even be purchased cheaper than printed books.

According to the records in the acquisition journal, Rescher occasionally received no fee for some manuscripts. In that period, notably, he can be said to have not sent manuscripts that could easily be found elsewhere, that were widely read among the public, and that did not stand out in terms of content. However, he did send different copies of some manuscripts. These different copies being found within the same shipment shows that this was a conscious behavior. He also sent some manuscripts that were not in good condition, probably because of their content.

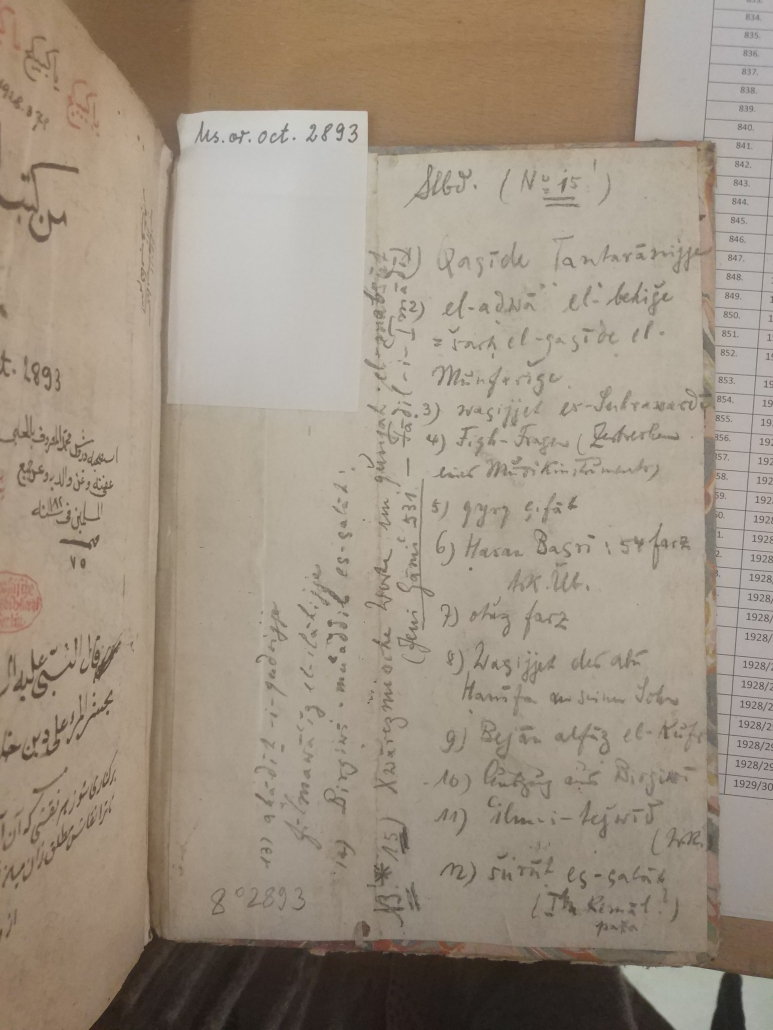

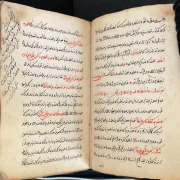

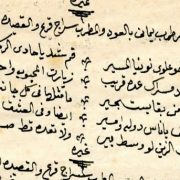

A significant portion of the manuscripts carry traces from Rescher. In most cases he would pencil in the necessary information on the inside cover, rarely at the end; he would indicate copies of the manuscript that were in other catalogues. From time to time, separate pages of notes sent by Rescher were seen to be attached to the relevant manuscript. Rescher may have benefitted from İsmail Saib Efendi while gathering this information.

Rescher’s inner cover notes that show the content of the manuscript Ms. or. oct. 2893, which he sold to the Prussian State Library in 1928. – Foto: Thoralf Hanstein / Lizenz: CC BY-NC-SA

The manuscripts received from Rescher were not considered a separate collection, nor were they given consecutive shelf numbers with respect to when they had been sent. Nonconsecutive numbers within same-size codes were given to the manuscripts, categorizing them with respect to size in accordance with the current procedure of the library at that time. The cataloguing process was also irregular. Uncatalogued manuscripts are currently being found among the Rescher manuscripts.

Conclusion

The study brings two basic claims to the agenda, beyond the detailed list it contains. The first is the assertion that regarding the manuscripts sold to the library (then: Staatsbibliothek Preußischer Kulturbesitz) after Rescher’s death as being Oskar Rescher’s personal manuscript collection is incorrect. These 1,722 manuscripts form a sub-par collection in terms of both physical characteristics and content and do not belong to Rescher. These manuscripts, which we know to have come from Istanbul, could easily be found in the city’s second-hand bookstores at the time they were sold to the library.

The focus of this study is on the manuscripts Rescher sold to the library between 1913 and 1936, procuring them from Turkish lands. The number and contents of these manuscripts as well as the magnitude of his trade activities had been unknown until today. The number of these manuscripts is 1,192, which is enough to establish a remarkable library in terms of physical characteristics and content.

The manuscripts Rescher had provided are on subjects that can be found in almost every manuscript collection. The subject headings can be exemplified as Qur’an, Qur’anic sciences, tafsir, qalam and aqidah, hadith, fiqh, faraiz, fatwas, catechism, Sufism, lineages, morality, dictionaries, versified dictionaries, grammar, divans, mathnavis, poetry majmuas, stories, history, law, prose majmuas, books on tabaqat (Islamic biographical collections organized by century), books on the life of the Prophet, manaqib (biographies emphasizing an individual’s merits, virtues, and remarkable deeds), geography, numerology, astrology, astronomy, algebra, geometry, chemistry, physics, diaries, calendars, medicine, biology, botany, and zoology.

In our opinion, Rescher could be considered to have performed a great service even if of the 1,192 manuscripts only the one shelf numbered as Ms. or. quart. 1988 had survived to the present. This manuscript, which was in a rather poor state when it arrived in Berlin, was given the name “Mecmua‑i Yek‑dest” by the compilers. We are conducting a series of studies on this manuscript, which has significant value in terms of presenting works that were widely read in the 17th century.

This study is hoped to open the door to other new studies. In addition, this study will pave the way for publishing lists of the manuscripts that Rescher had sold to other libraries, thus contributing to the creation of an inventory of the manuscripts that were sent abroad from Istanbul when the Ottoman State had disappeared from the stage of history.

This blog entry is based on a bilingual article (Turkish, English) published in:

İslam Tetkikleri Dergisi – Journal of Islamic Review 11, 2 (2021): 477‑568

The information contained in the introductory section is in part based on our extensive study of Rescher, please see:

Güler Doğan Averbek – Thoralf Hanstein, “Oskar Rescher – Biographical Finds around Manuscripts, Books and Libraries”, in: Sammler – Bibliothekare – Forscher: Beiträge zur Geschichte der Orientalischen Sammlungen an der Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, ed. Sabine Mangold-Will, Christoph Rauch, Siegfried Schmitt. – Frankfurt/Main: Vittorio Klostermann Verlag, 2021: 387–449

(Zeitschrift für Bibliothekswesen und Bibliographie – Sonderbände, 2021)

Thus, thanks to Mr Hanstein for his contribution and permission to present this study here.

Frau Dr. Güler Doğan Averbek, Marmara University, war im Rahmen des Stipendienprogramms der Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz als Stipendiatin des Jahrgangs 2020 an der Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin. Forschungsprojekt: „Reconstruction of Oskar Rescher’s life and works as an Orientalist. A life between Germany and Istanbul“

Vorträge der Stipendiatin zu Oskar Rescher:

- Presentation „Fuat Sezgin’s Uncompleted Project on Brockelmann: Oskar Rescher’s copy of Geschichte der arabischen Litteratur (GAL)“ (in Turkish)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6lF-BviZYCU

- Conference: Oskar Rescher and Manuscript Trade in the Early Republican Period in Turkey (in Tıurkish)https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FS6s9_s0DaQ&t=207s

Foto: SBB-PK / CC BY-NC-SA

Foto: SBB-PK / CC BY-NC-SA

CC-BY-NC-SA

CC-BY-NC-SA Public Domain

Public Domain

Public Domain

Public Domain bpk 70000010

bpk 70000010  \pk.de\sbb\Abteilungsdaten\IID\IID_2_Wissenschaftliche_Dienste\01_uebergreifendeAufgaben\Wissenswerkstatt\Social_Media\Blog\Blog ua Lektuere Tipps\Zeitungen\

\pk.de\sbb\Abteilungsdaten\IID\IID_2_Wissenschaftliche_Dienste\01_uebergreifendeAufgaben\Wissenswerkstatt\Social_Media\Blog\Blog ua Lektuere Tipps\Zeitungen\ \pk.de\sbb\Abteilungsdaten\IID\IID_2_Wissenschaftliche_Dienste\01_uebergreifendeAufgaben\Wissenswerkstatt\Social_Media\Blog\Blog ua Lektuere Tipps\Zeitungen\

\pk.de\sbb\Abteilungsdaten\IID\IID_2_Wissenschaftliche_Dienste\01_uebergreifendeAufgaben\Wissenswerkstatt\Social_Media\Blog\Blog ua Lektuere Tipps\Zeitungen\

Ihr Kommentar

An Diskussion beteiligen?Hinterlassen Sie uns einen Kommentar!