Manuscripts in Motion: Five Processionals for Dominican Nuns in the Collections of the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin

Gastbeitrag von Prof. Claire Taylor Jones

It was a warm day in June 2023. I had been looking at an awful lot of books, including a large set that disappointingly turned out to be numerous copies of the same, fairly commonplace thing. Truth be told, I was starting to get a bit bored. That’s a risk you always run with exploratory research; when you’re not sure what you’ll find, there’s a chance you might not find anything. I feared that might be the case here. I had started out my research stay in the Music Department of the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin looking at graduals and antiphonaries from the Cistercian convent of Porta coeli in Schweinheim (Mus.ms. 40215–Mus.ms. 40220). These large-format choir books are enormously tall volumes of music, written in huge script to be visible from a distance, and so heavy that it takes two people to carry them from the front desk to the reading tables – and their standard set of chants was hardly worth that effort! That day, for a change of pace, I had requested several smaller manuscripts, including an unassuming book, bound in brown cloth, about the size of a short novel. I took it back to the reading table, bedded it on the foam wedges that protect the books’ old and delicate spines, and sat down to work. As I opened the cover, gold caught the light of the reading lamp and flashed in my eyes. A thrill ran through my body and a startled “oh!” escaped my throat into the silent reading room. This was it! I had thought it was lost, but this precious object was here in my hands. It had been in Berlin all along.

I study the liturgy of the medieval Dominican order, focusing on manuscripts produced between the thirteenth and the sixteenth centuries by and for nuns. “Liturgy” is an umbrella term for Christian ritual. Its meaning was once restricted to the mass, at which Christ’s sacrifice is commemorated through consecration of the Eucharist. Scholars now consider a much broader variety of institutionalized rituals as liturgy: the daily prayer hours of the divine office; rites such as baptism, marriage, and royal coronation; and the processions that Christian communities conducted on important holidays or for votive purposes (e.g., praying for rain). This final category is particularly interesting, and I have spent several years studying a type of manuscript called “processionals”.

These books are small enough to carry around easily, so that people can sing from them while walking in a procession. Because each nun needed her own processional (see the illustrations in the bottom margin of New York, Morgan Library, MS M.1214), they proliferate in collections of medieval European manuscripts. Indeed, the gilded book I happened upon in Berlin belongs to a group of more than thirty known processionals from the royal convent of Poissy in Paris. The Poissy processionals are rightly famous not only for their rich and vibrant illuminations (paintings in and around the text on a manuscript page) but also for the unusually high number of chants for the altar-washing ceremony on Maundy Thursday.

On this day, the cloths and ornaments were stripped from church altars, and the altars were left bare until Easter three days later. It was traditional to cleanse the church during this time, and many communities practiced a form of ritual purification. Each altar was cleansed with water and wine (symbolizing the water and blood that poured from Christ’s side at the crucifixion) and scrubbed with a rough brush (commemorating how Christ was scourged before the crucifixion).

The altar-washing ceremony is particularly interesting to study in the Dominican context because it was hyperlocal. The Dominican order invested substantial energy into designing, disseminating, and enforcing a uniform liturgy that could be practiced in the same way in each affiliated community. The intended uniformity was so rigid that it influenced the visual representation of music. In late medieval Germany, melodies were commonly written in Gothic, or “Hufnagel” notation, as can be seen in this processional from Gernrode Abbey near Quedlinburg in Saxony-Anhalt.

Abb. 3: Pueri hebreorum tollentes in Hufnagel notation, SBB‑PK: Mus.ms. 40080, f. 91v–92r. – Photo by C. T. Jones

However, Dominican manuscripts – even those produced in Germany for German users – were written in the square notation of France and Italy. Although less expertly executed, the musical notation in the processional from Holy Cross in Regensburg matches that of the Poissy manuscript produced in Paris.

Abb. 4: Pueri hebreorum tollentes in square notation from Regensburg, SBB‑PK: Mus.ms. 40629, f. 5r. – Photo by C. T. Jones

Abb. 5: Pueri hebreorum tollentes in square notation from Poissy, SBB‑PK: Mus.ms. 40599, f. 18v. – Photo by C. T. Jones

Although the Dominicans achieved remarkable success in standardizing their liturgy throughout Europe, they could not pin down Maundy Thursday’s altar washing. Each church had a different number of altars, each of which was dedicated to a different saint. During the ritual on Maundy Thursday, Dominican communities walked in procession to each of the altars in their church and sang a chant in honor of the saint to whom that altar was dedicated. Because each community had different saints in different combinations, each Dominican community performed this ritual with chants unique to that community, creating a pocket of diversity in religious uniformity. Indeed, this ceremony is often the only way to tell where a manuscript came from.

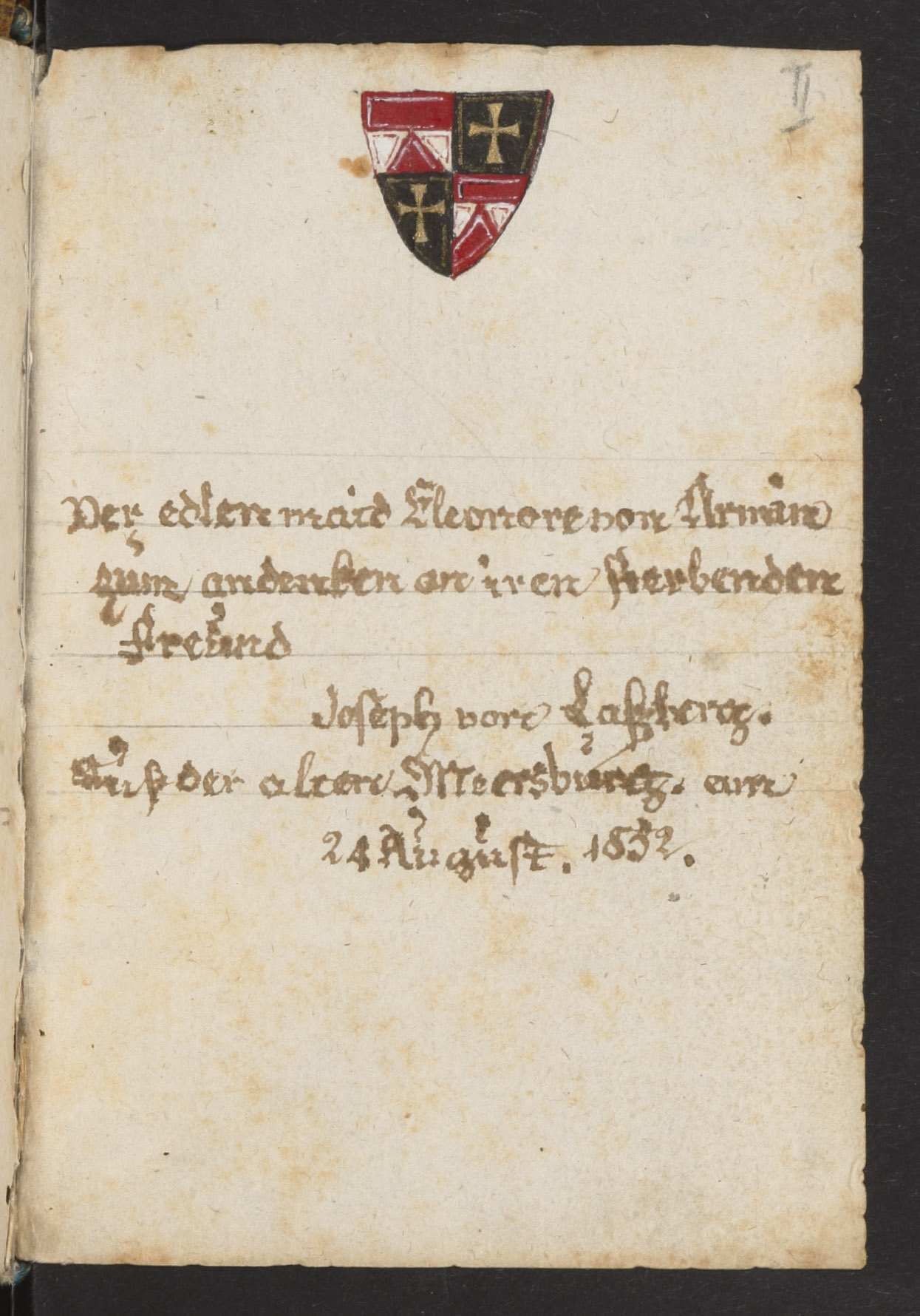

The Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin owns no fewer than five processional manuscripts that were made for Dominican nuns. Only one of them, Hdschr. 49, lacks the unique chants for the altar-washing ceremony, so it cannot be localized precisely. It was used in a German-speaking community, since the rubrics (titles) are given in German, even though all the chants are still in Latin – the official language of the medieval church. This book has an unexpected connection to the German literary canon. On the opening page, a nineteenth-century inscription reads: “To the noble maiden Eleonore von Arnim in memory of her dying friend, Joseph von Laßberg. From the old Meersburg, 24 August, 1852.”

Joseph von Laßberg (1770–1855), an author and antiquarian, was married to Jenny von Droste zu Hülshoff (1795–1859), the older sister of renowned author Annette von Droste-Hülshoff (1797–1848), who spent her last years living in Meersburg with her sister and her brother-in-law. How this small medieval processional returned to the family is not clear, but it came to the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin with the estate of Annette von Droste-Hülshoff, much of which is on permanent loan in Münster.

All four of the other Berlin processionals contain the chants for the saints as part of the altar washing. Each has a different number of altars ranging from three in the tiniest German manuscript to twenty-one in the richly decorated Poissy processional.

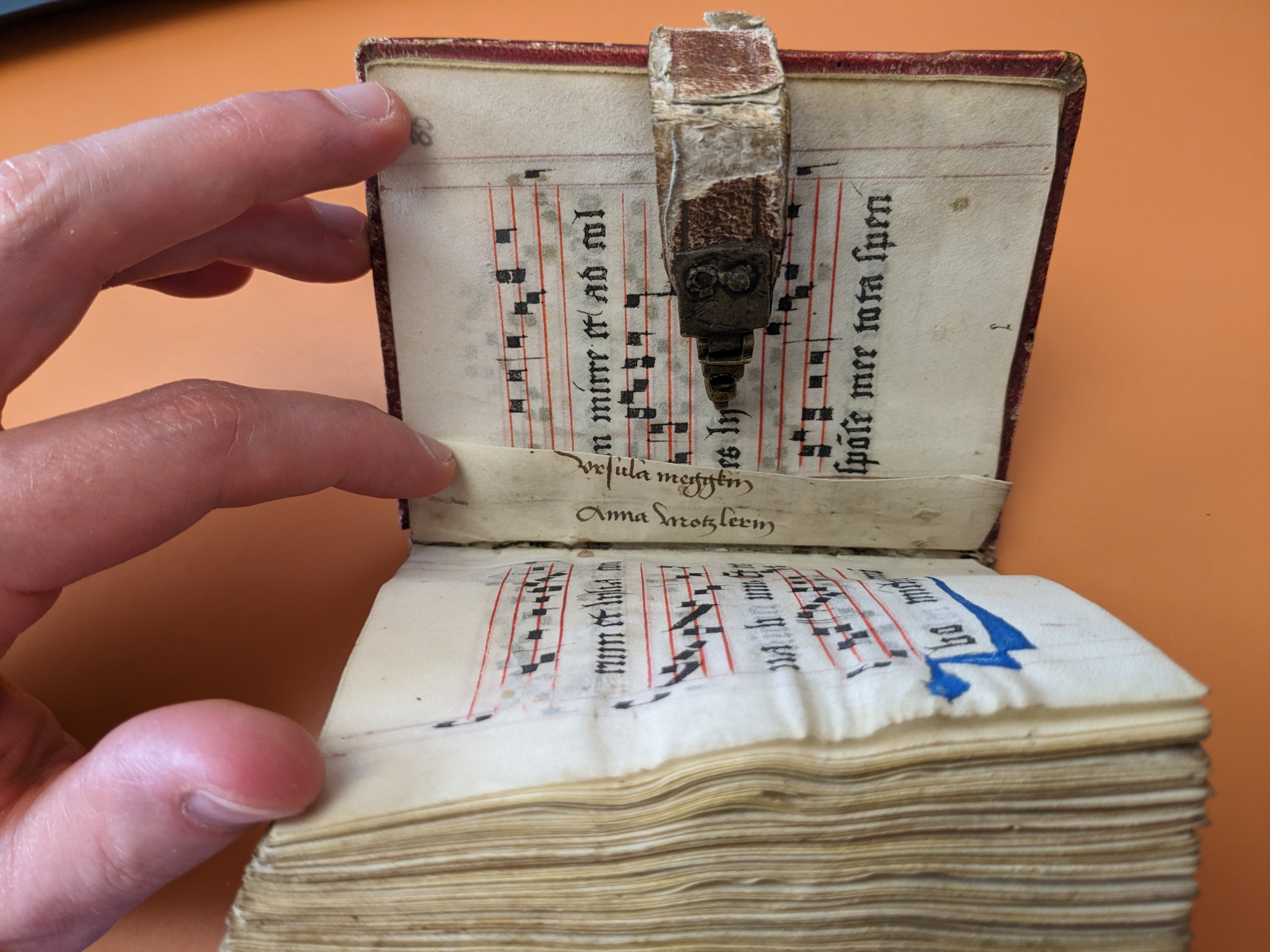

Even though the smallest manuscript (Mus.ms. 40649) has three chants for saints during the altar washing (Regali ex progenie for the Virgin Mary, Valde honorandus for John the Evangelist, and Magne pater for Saint Dominic), I have not been able to identify the community it came from. Still, this book contains other clues to its origin: the names of three women. At the end of the manuscript, the scribe recorded her own name, “Sister Dorothy v. R. wrote this book.” Moreover, a tiny scrap of paper peeking out between two folios contains the names Ursula Meggkin and Anna Motzlerin. Finding these names in other records or convent archives may provide the key to the location where these women made and sang from their tiny books.

The messy and sparse character of this small German manuscript stands in stark contrast to the gilded excess of the Poissy processional (Mus.ms. 40599). The convent of St. Louis in Poissy, located just outside Paris, was founded around 1300 by Philip the Fair, King of France from 1285 to 1314. As a royal foundation, it continued to attract noble and wealthy women. In contrast to the small German processional written by a nun, this Poissy manuscript and others like it in Heidelberg, Philadelphia, Paris, and Sydney, etc., were made by a high-end professional workshop, not by the aristrocratic women themselves. That the scribes and artists who produced this manuscript were not familiar with its contents is evident from silly errors. For example, the illuminator who entered the initial letters mistook [_]eniores for [_]emores and wrote an M for Memores instead of an S for the correct word, Seniores.

Abb. 8: The Memores error at the bottom of the left page, SBB PK: Mus.ms. 40599, f. 39v. – Photo by C. T. Jones

The fact that no annotations correct the mistake may mean that the wealthy women of Poissy owned these books as luxury items and did not observe the liturgy as Dominican nuns were supposed to. Whoever owned this book never noticed that the word was wrong.

Annotations abound in the final two manuscripts I will discuss here – a processional from St. Katharina in Nuremberg (Ms. theol. lat. qu. 144) and one from Holy Cross in Regensburg (Mus.ms. 40629). The Nuremberg manuscript signals the changes by a tiny note on the first folio, “This book has been corrected.”

Abb. 9: Annotation dz puch ist corigirt, SBB‑PK: Ms. theol. lat. qu. 144, f. 1r. – Photo by C. T. Jones

The corrections were rendered necessary because the route for the altar‑washing ceremony in this convent changed in the late fifteenth century after two new altars were dedicated, including one for the famous Italian mystic Catherine of Siena. The new altars were inserted into the route, and the community changed the order in which some of the others were visited. To bring this processional into line with the new version of the ceremony, the folios with the chants in the wrong order were ripped out and the incipits (opening words) of the correct chants were written into the margins in their proper places in the new ceremonial order. The removed folios were not replaced, so the manuscript now lacks the full musical notation for many of the chants indicated in the margins.

Abb. 10: Marginal annotations on both folios, SBB‑PK: Ms. theol. lat. qu. 144, f. 14v–15r. – Photo by C. T. Jones

Something similar happened in Regensburg, although the manuscript was not altered so dramatically. In this case, a later user scrawled a new chant in the lower margins and then numbers in the side margins to show the order in which the chants were sung.

Abb. 11: Numbering in the Holy Cross processional, SBB PK: Mus.ms. 40629, f. 28v–29r. – Photo by C. T. Jones

Although these manuscripts cannot match the rich splendor of the Poissy processional, such hints about the lives, activities, and changing practices of past women are the gold that I mine in the archive.

In summer 2022, I sat in the Music Reading Room of the Staatsbibliothek on Unter den Linden and flipped through an auction catalogue from 1928. In that year, the manuscript dealer Martin Breslauer printed a book of descriptions and images to advertise the sale of the jurist and musicologist Dr. Werner Wolffheim’s impressive collection. My eye lingered wistfully over two manuscripts in particular – both Dominican processionals, one clearly from Poissy and one with extensive ritual instructions in German. What had become of these manuscripts? Who had bought them? Did they perish in the war that ravaged Europe just a few years later? I slunk up to the desk and whispered to the librarian. Where was the catalogue for medieval manuscripts in the music collection? I had found the catalogue for books of polyphony, but what about the single-voice liturgical music? None has ever been published and, for details, I would have to look at the manuscripts myself. With the generosity of a short-term fellowship from the Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz, I was able to return in June 2023. I had not dreamed that I would find those very two manuscripts from the Wolffheim auction, one year later sitting in the very same room. The Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin still holds innumerable treasures, waiting to be found.

Frau Prof. Claire Taylor Jones, University of Notre Dame, war im Rahmen des Stipendienprogramms der Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz im Jahr 2023 als Stipendiat an der Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin. Forschungsprojekt: „Nichtkatalogisierte liturgische Handschriften in der Musiksammlung der Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin“

Foto von C. T. Jones

Foto von C. T. Jones

Foto: Sanjiao Tang

Foto: Sanjiao Tang https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/deed.de

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/deed.de ![F[riedrich] E[duard] Bilz, Das Neue Naturheilverfahren: Lehr- und Nachschlagebuch der naturgemäßen Heilweise und Gesundheitspflege, Vol. I (Leipzig: Verlag von F.E. Bilz, 1898](https://blog.sbb.berlin/wp-content/uploads/IMG_2063a-180x180.png)

Ihr Kommentar

An Diskussion beteiligen?Hinterlassen Sie uns einen Kommentar!