Time Unfolded: A Late Medieval Concertina Calendar in the Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin (Libr. pict. A 92)

Gastbeitrag von Dr. Sarah M. Griffin

The diffusion of mechanical clocks in fourteenth-century Europe introduced new systems of tracking time. Many of these converged in late medieval calendars, which contain details of the yearly cycle that were calculated by astronomical observation and ordered through liturgical routine. During this period, the calendar broke free from its traditional book form and came to be found in scrolls, almanacs, atlases, printed books, disks within astronomical clocks, painted triptychs and even hunting knives. A particularly interesting example of these new forms are concertina calendars: manuscripts that included pictorial expressions of the calendar that could be folded out like an accordion in order to be read.

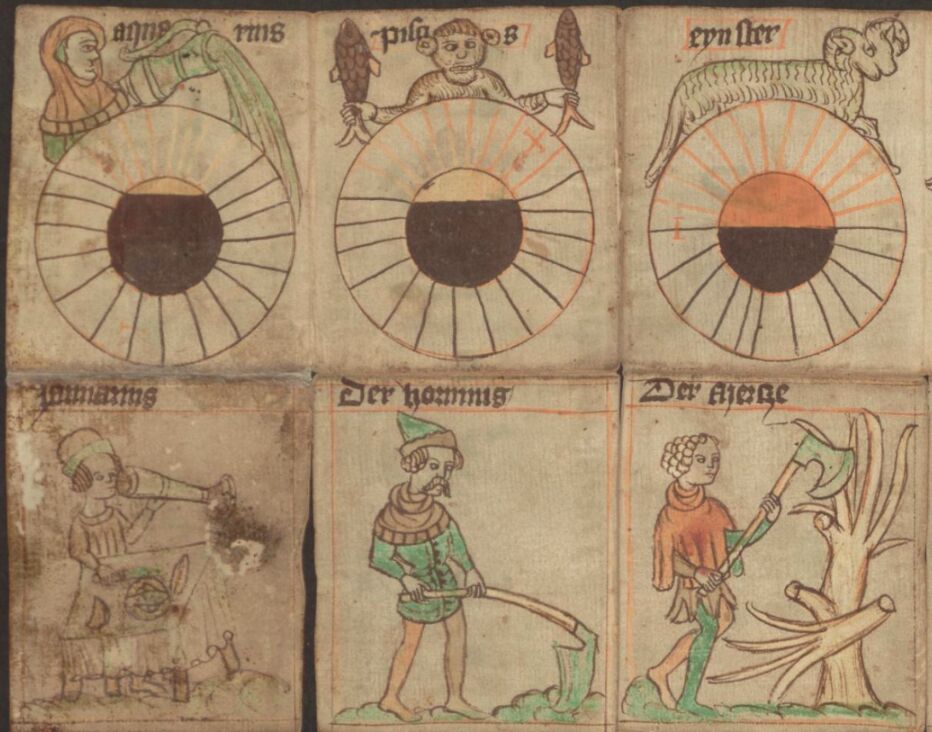

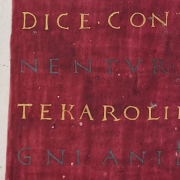

The Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin houses one of these rare manuscripts: Libr. pict. A 92 (available to view online), which I have come to call the ‚Berlin calendar‘. Made around 1400 in central Germany, the Berlin calendar consists of one large, folded piece of vellum. On one side is a pictorial saints‘ calendar (a month of which is shown in the banner above) where the most important feast days are illustrated. Usually they are depicted as the bust of a saint who is celebrated on that day, such as Saint Barbara on the left, who holds a tower. On the other side of the vellum (image 1) are the labours of the months, each undertaking an activity suitable for that month, and signs of the zodiac accompanied by curious circular diagrams that, through their varying degrees of fullness, express the average hours of daylight and darkness for each month. The latter are particularly revealing as to contemporary time-keeping practises.

Image 1: Labours of the months and wheels of daylight and darkness from January to March. – Detail of Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, Libr. pict. A 92, Germany (c. 1400) – Public Domain

During a two-month stay at the Staatsbibliothek from July to August 2019, I tasked myself to better understand the Berlin calendar and how it would have been used in the Middle Ages by considering it within a group of similar concertinas. In addition to forming a focused analysis of the function of concertina manuscripts, their study informed a larger project on the role of different forms of calendar in daily time-keeping during the fifteenth century.

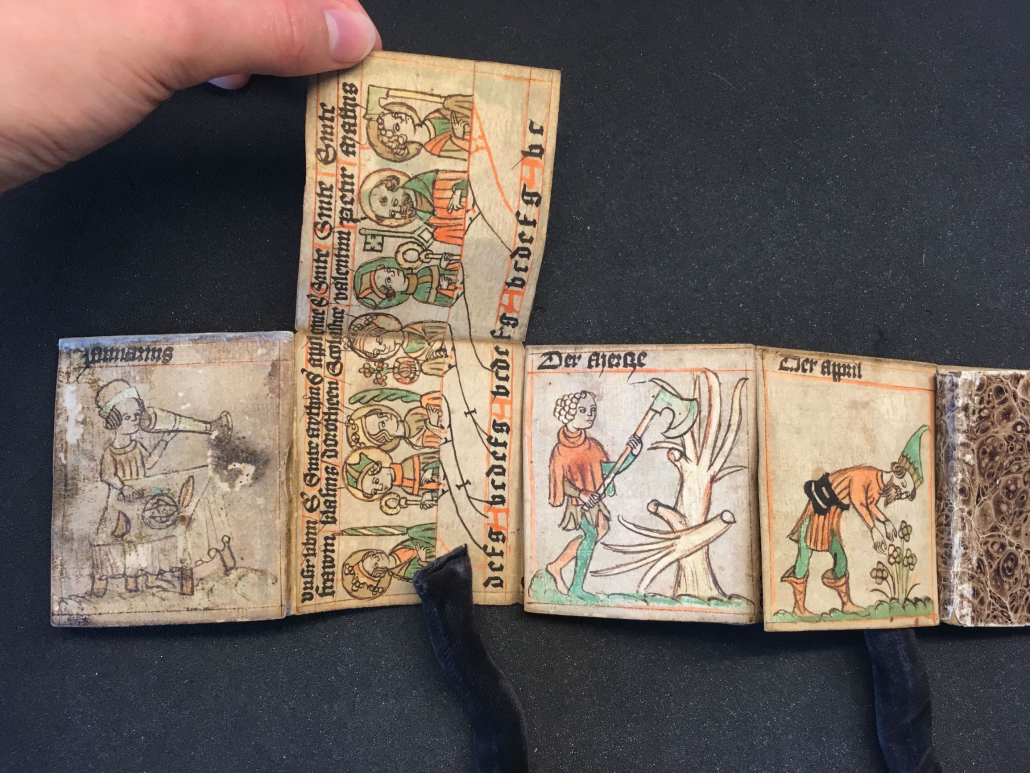

Concertina manuscripts, sometimes referred to as accordion books, provide rich and fascinating insight into the reading practices of the later Middle Ages while showing the potential of the manuscript medium to render complex and interactive three-dimensional forms. They must be unfolded to be read, and are designed in such a way that they can be unfolded in various orientations to reveal different sets of content. This structure provided the medieval maker with the potential to link different pockets of information through the multiple ways in which the manuscript could be folded and unfolded. The Berlin calendar is a particularly important manuscript for the understanding of how concertinas were read because it is still in its folded form, whereas many others have been unfolded and mounted onto boards to ensure they cannot be folded again. Although the manuscript has been digitised, it was absolutely essential that it was consulted in the flesh for the multiple patterns of its unfolding to be understood. The fragility of the parchment and the repetitive unfolding and refolding of its parts meant it could only be consulted four times over the Summer, making my time with the manuscript even more precious.

Image 2: Detail of Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, Libr. pict. A 92, Germany (c. 1400): Unfolding February. – Photo: Sarah Griffin; CC-BY-NC-SA

Research on folded medieval manuscripts has flourished in recent years, thanks in part to the publication of J. P. Gumbert’s ‚Bat Books‘: a catalogue of folded manuscripts that Gumbert worked on from the 1990s onwards, only to be published shortly before his death in 2016. Gumbert managed to consult almost every single of the sixty‑three folded manuscripts surviving, barring just three. From his first-hand experience of their handling, he created the wonderful term ‚bat book‘ to describe them, as ‚when in rest they hang upside-down and all folded up, but when action is required they lift up their heads and spread their wings wide‘. Gumbert’s work led me to study concertinas in other collections, including a Dutch concertina calendar in the Germanisches Nationalmuseum (Nuremburg) made almost contemporaneously to that now in Berlin.

By consulting these calendars both in person and online I was able to identify eight manuscripts (from Gumbert’s twenty‑one concertinas) that share the same model. Studying the Berlin calendar within this group was like piecing together a three-dimensional jigsaw puzzle. I used the content and layout of the other manuscripts to evaluate which parts of the Berlin calendar were missing, if any at all. As well as providing potential sources for it, the unique features of the Berlin calendar could also be identified. Not only is it the only surviving German concertina, it is also the only calendar not to contain the Golden Numbers, which are essential to calculate the moveable feast dates, such as Easter. This raises the question of whether it is unfinished or whether it was made for a different purpose. The findings of this research will form an article on the reading practices of this particular model of concertina calendar and where the Berlin calendar fits into the group.

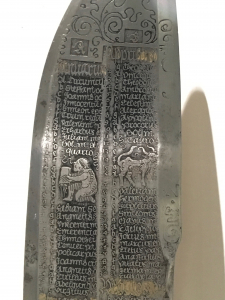

In addition to informing this dedicated study, the two-month stay in Berlin allowed me to visit other German collections that hold objects of primary significance to the larger project. Building upon previous research on a monumental calendar from Verona that is associated with the earliest astronomical clocks (the published outcome of which is available online), I was glad to consult a large wooden calendar disk made for Lübeck’s first astronomical clock, originally in the Marienkirche (Lübeck, St. Annen‑Museum, c. 1461, Inv. no. 1892‑145); a large calendar volvelle in the form of a triptych (Nuremburg, Germanisches Nationalmuseum, 1461, Inv. no. WI58); and a sixteenth-century hunting knife made by Ambrosius Gemlich, into which he etched a beautifully-detailed liturgical calendar (Munich, Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, Inv. no. 13/1174, see image 3). However, it was not always necessary to leave Berlin. The Staatsbibliothek houses many other calendrical curiosities, including a sixteenth-century wooden calendar (Libr. Pict. A 75, see image 4) whose saints‘ calendar is similar in format to the Berlin calendar.

Image 3: Calendar etched into a hunting knife by A. Gemlich, 16th c.: Detail of January, February, April and May. – Munich, Bayerisches Nationalmuseum, Inv. no. 13/1174 – Photo: Sarah Griffin; CC-BY-NC-SA

Image 4: Detail of wooden calendar showing February, 16th c. – Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, Libr. pict. A 75 – Photo: Sarah Griffin; CC-BY-NC-SA

From the selection of calendars mentioned above, one can observe the variety of forms in which they were crafted during this period. Their first-hand analysis can reveal how time was ordered and understood in the late Middle Ages, a period defined by the introduction of mechanical time-keeping and in which the methods of measuring time were in transition.

Associated sources:

P. J. Becker, Aderlaß und Seelentrost: Die Überlieferung deutscher Texte im Spiegel Berliner Handschriften und Inkunabeln (Mainz, 2003), pp. 378‑80, no. 181

J. Borland, ‚Moved by Medicine: The Multisensory Experience of Handling Folded Almanacs‘, in Sensory Reflections: Traces of Experience in Medieval Artifacts, ed. by F. Griffiths and K. Starkey (Berlin, 2018), pp. 204‑24.

S. M. Griffin, ‚Synchronising the Hours: A fifteenth-century wooden volvelle from the Basilica of San Zeno, Verona‘, in Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, LXXXI (Dec., 2018), pp. 31‑67

J. P. Gumbert, Bat Books: A Catalogue of Folded Manuscripts Containing Almanacs or Other Texts (Turnhout, 2016)

Erik Kwakkel, ‚The Incredible Expandable Book‘, accessible at medievalbooks, https://medievalbooks.nl/tag/accordion-book/

C. Silva, ‚Opening the Medieval Folding Almanac‘, in Exemplaria, 30:1 (2018), pp. 49‑65

R. Wieck, The Medieval Calendar: Locating Time in the Middle Ages (New York, 2017)

Frau Dr. Sarah M. Griffin, Winchester College, war im Rahmen des Stipendienprogramms der Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz im Jahr 2019 als Stipendiatin an der Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin. Forschungsprojekt: „Hours of Daylight, Hours of Darkness: The Visualisation of Time in a Late Medieval Almanac (Libr. pict. A 92)“

https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/mark/1.0/deed.de

https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/mark/1.0/deed.de![Andachtsbuch : Ms. germ. oct. 2 , [15. Jh.] SBB-PK http://resolver.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/SBB00015AE400000021 Andachtsbuch : Ms. germ. oct. 2 , [15. Jh.] SBB-PK http://resolver.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/SBB00015AE400000021](https://blog.sbb.berlin/wp-content/uploads/Lektuere_Handschriften-180x180.jpg) Digitalisierte Sammlungen http://resolver.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/SBB00015AE400000021

Digitalisierte Sammlungen http://resolver.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/SBB00015AE400000021 bpk 70000010

bpk 70000010  Public Domain

Public Domain

Bildausschnitt: Aquarell Breslau, Zuchthaus. Aus: Stridbeck, Johann: Skizzenbuch : Ms. boruss. qu. 9a , 1691. SBB-PK

Bildausschnitt: Aquarell Breslau, Zuchthaus. Aus: Stridbeck, Johann: Skizzenbuch : Ms. boruss. qu. 9a , 1691. SBB-PK  SBB-PK CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

SBB-PK CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

Ihr Kommentar

An Diskussion beteiligen?Hinterlassen Sie uns einen Kommentar!